“INDIAN FOOD IS BASED ON YOUR MEMORY, and the story,” Sujan Sarkar says.

The chef at Rooh Chicago, Sarkar has the dark-eyed, intense look of his native Kolkata, and an equally intense manner of speaking about Indian cuisine.

“As an American—I don’t want to say that you don’t have that much knowledge, but you’re not exposed to all of Indian food, because it’s quite big. But in India, we don’t know much about Indian food, either! We only know about our own different regions. So the local [American] people, when they’re coming here, they’re open for what we are serving. But it’s kind of a challenge for Indian people,” because what any restaurant offers is not necessarily the particular style of Indian food they’re used to.

The question for me is not just which part of India the food comes from, but how Indian is it? Is he trying to be authentic to cooking in India, or is there already an Indian-American fusion cuisine, as there is Italian-American, or Chinese-American, that you inevitably fall into here? Certainly the talk in Chicago of late has been focused on very American notions of hipster fusion Indian.

Sujan Sarkar

Sarkar says of the typical Indian cook who emigrates to another country, “Whenever we open an Indian restaurant, it’s all about adapting to their kind of food. And what I do is just opposite—this is an Indian restaurant. This is not an American Indian restaurant, this is an Indian restaurant in America. When you call it an Indian restaurant in America, it’s our flavors, it’s all based on Indian flavors.”

“We are progressive, but we are not fusion,” he says. “We are not mixing different cuisines, we are exploring more possibilities with new ingredients, what is locally available here.” He gives an example—”In India, we do not get good quality asparagus. So how can it be part of our cuisine? It’s not possible.”

“But we are not [making fusion food] with soy sauce, or oyster sauce. We are doing with asparagus what we would do with green beans. We are making the same kind of flavors, using what is available here.”

He rattles off more things he’s learning to use here. “Artichoke, sunchoke, kale, we use a lot. Now, green chickpeas are coming, they are amazing. In India we get that, but they’re smaller. It’s fall, so different kinds of squash, pumpkin, rhubarb, in both sweet and savory dishes. Savoy cabbage, we use sometimes. We use instead of cauliflower, Japanese caulilini, that really works well in a few things. Beetroots, radishes, tons of things,” he says, lighting up with the excitement of all these new items to play with.

“It’s the same thing with different kinds of meat. Again, because India is so diverse, some parts of India they don’t eat pork, some they don’t eat beef, in the coastal areas they’re more seafood based. Here, we can get ingredients which are top of the top quality.

“In our menu, we are doing a whole sea bass, we have monkfish which is amazing, we have short rib, we have three different cuts of lamb, we have duck. We use truffle where it’s necessary. The menu is so diverse, it’s not just one thing.”

“Are there ducks in Indian cuisine?” I ask, not sure if I’ve seen that or not before.

“Yes!” he says enthusiastically. “In Kashmir you will see duck curry. Also, in the south, but it’s a completely different way they cook it. In Kashmir it’s with turnips, but when you go to the south, that is also a curry, but it’s more dry, and based on coconut milk. The south and western part is all based on coconut milk, and when you go north, on that side, it’s more yogurt or butter, because that’s what they have.”

“The possibilities are endless—you can do so much!” he says of what he’s cooking here. “But we try to find the balance. We don’t give you everything new, because then you’re confused. So we have butter chicken on the menu, but done in such a way that it’s traditional. But again, the flavor, using the spices, the story—that’s Indian.”

Spices on the line

SUJAN SARKAR’S OWN STORY IS INDIAN, but it’s also international, in both location and the cuisines he was cooking at a given time. He started his career in a J.W. Marriott hotel in Mumbai, but went to Dubai and then to London, where he ascended through many of the glitziest names there (Jamie Oliver’s Fifteen, Freemasons, Cipriani, the private celebrity haunt Almada), winning assorted nominations as best chef in London or the U.K. He jumped to fame back in New Delhi as the chef of Olive Bar & Kitchen, being named Chef of the Year by the India Times in 2016, and became celebrated as India’s best-known disciple of the Modernist Cuisine books, whipping out the liquid nitrogen and the maltodextrin at a tasting menu side project of Olive Bar called The Tasting Lab.

And now he’s joined up with the partners behind Rooh, Vikram and Anu Bhambri, who have the original Rooh in San Francisco as well as Baar Baar in New York, to open elevated Indian restaurants in America. In India they created restaurants focused around western ways of dining out, including artisanal cocktails; bringing that mix of Indian flavors with western lifestyles from India to America makes perfect sense for a well-educated Indian audience traveling back and forth between both cultures.

But it means he’s gone from celebrity chef in India—something that had never really existed before—to relative obscurity in a city, and neighborhood, where Izards and Baylesses and Vivianis walk the earth. (Though when I ask if he misses being a celebrity, he waves it away and says, “India doesn’t have famous chefs.”) Why did he decide to come to America?

“It’s not that I decided to come, it just happened,” he says. “I was not that keen to come to the United States, because most of my career, I lived in London. And I was doing modern European and French. I used to run one of the biggest standalone restaurants in central London, in Mayfair [Automat]. Then I went back to India to work with Indian flavors and just travel around, and do something which can also give me satisfaction.”

As late as the San Francisco Chronicle’s review for Rooh in 2017 he still had molecular gastronomy impulses, but he backs away a bit from that now. “We do use some techniques, but it’s not that scary,” he says. “I don’t use dry ice on the table. We are doing more texturizers, I would say. It’s more about the consistency than the showman aspect of it. For instance, [in India] we eat something called curd rice, a sour rice preparation, with rice and a little bit of spices, it gives a little bit of sour taste. And that, we are turning into a rice hollandaise, but there is no egg or butter. It goes with our wonderful dish, cauliflower koliwada.

“When we do a special dinner, then we go one step ahead—because you know, it’s a big restaurant, we have two floors and a hundred and sixty seats. That kind of cuisine, you need much more detailing, that only can happen when you have less number of people.”

We cook everything fresh here. In India, what you cook you eat. You don’t keep it in the fridge.

Instead, working in the Bay Area seems to have pushed him in more of a farm to table direction. “Rooh in San Francisco, we are getting things from the farmers market twice a week. Because when you go to the farmers market there, you get a lot of Asian vegetables which are not available from any supplier,” he says. In Chicago, he’s still building his retinue of suppliers, getting his chickens and some other meats through D’Artagnan, a national specialty distributor—”It’s a process. But everything takes a little time. We have a source for everything we get here, and process everything here—even our spices, our breads, all the desserts, even our ice cream—we try to do everything in house.”

“In India, what you cook you eat. You don’t keep it in the fridge,” he says. “We cook everything fresh here. Our chicken, we know the source where it is coming from. And that’s why our cuisine is more elevated than any other Indian restaurant in the country, not just Chicago. A lot of new dishes, a lot of surprises on the menu. 40% of the menu is vegetarian, and we have a lot of vegan dishes.”

Cocktail menu

“WE THINK ABOUT OUR design, our cocktail menu, music—everything’s come together. It’s not only food, you don’t come to a restaurant nowadays only for food,” Sarkar says. Not in the West Loop, certainly.

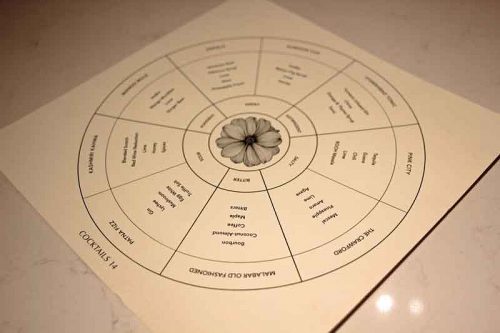

At a media preview early in the summer, I was especially impressed by the thinking behind the cocktail menu. India did not have a preexisting cocktail culture with food—Sarkar is one of the main people who helped invent it, at a bar called Ek Bar in New Delhi—but what it does have is a deep cultural reservoir of notions about food and drink and health in ancient Ayurvedic medicine. The menu, shaped like a wheel, ingeniously displays cocktails according to vaguely Ayurvedic notions of how you balance things like sweetness and bitterness, simplified to a level where slightly sozzled Americans can make use of them.

“This is New India, there is no definition” for how you do things like make a cocktail menu, he says. “But I don’t want to feel disconnected, I always want to be connected with India. So the cocktail menu is based on six different tastes of Ayurveda. It’s not Ayurvedic cocktails, there’s no such thing,” he laughs, a little nervously as one might when approaching blasphemy. “But think of Japanese food, there’s five different tastes, including umami, that define Japanese cuisine. Similar, in Ayurveda there are six different tastes, not five. So we brought that to a cocktail wheel with all the tastes, which all overlap. And you see that you cannot just drink a bitter drink—you have to balance it out.”

Cocktails at the beginning of a meal are one adaptation to western ways; another is desserts at the end. India, of course, has a great tradition of sweets, but Sarkar says “It’s not possible to do Indian dessert here. The guys who are Indian confectioners do only that. That’s why again, I have to do something I am good at, using the flavors of India to present something that, you know it is Indian, but presented in a modern way.”

A green pea and cheese kulcha goes into the tandoor

Another thing that interests me, especially after having tried some of it at the media preview, is their baking program—the kitchen is striking because 90% of it could be any kitchen in Chicago, and then there’s the one difference: a gas-powered tandoor at the end of the line, for baking Indian breads, mostly by adhering them right to the stone wall of the tandoor, as if you were frying a pancake in space. Everyone is familiar with naan, the ubiquitous white-bread-of-India, but Sarkar makes references to several different forms of baking, including kulcha stuffed with fillings, or the rolls called pao or pav, which he has changed for, I guess, American tastes.

“We upgraded the recipe a little bit, so it’s much lighter,” he explains. “It’s more like a brioche. Also we make one called taftan, it’s kind of a flatbread—you’re never going to see those kinds of things in an Indian restaurant here. We’re also going to make one called polli, from Goa. But we make all our breads in house, so they can go in the tandoor when you order them. Nothing is made before.”

Taking the kulcha out of the tandoor

Kulcha topped with goat cheese and shaved truffle

Rooh seems well organized to introduce Chicagoans to Indian cuisine on a level more sophisticated and varied than the Devon buffets with their dozen endlessly repeated dishes—though there’s also a challenge in the rise of hipster fusion dishes, invented on the fly. At the same time, though, Sarkar stresses that the variety of Indian cooking is virtually endless. “In the West, you only see South Indian restaurants, there is nothing else. It’s not always about curry—there are hundreds of curries in India. But it is a name; there is nothing called curry.

“There is a story behind every dish. There is no recipe for Indian food. People try to put this in a book, but first thing, dal is a simple lentil preparation. At my house, how my Mom is still doing it—and we think we are the best—my next door neighbor does it completely different. It’s not recipe driven, it’s all about the story behind it.

“We are not saying we are the best, but I am trying to bring those flavors, as close to India as possible. So when I make the dal, the dal is different, the onion is different, your tomato is different. But the process is the same. Whatever we are doing, there is a process, there is a method, and nothing is random.

“It’s new, but trust me, this is the future of Indian cuisine,” he says. If it works out that way, he might get well known here yet.

Michael Gebert is the media Moghul of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.