HEAT RISES FROM DUSTY, CRACKED PAVEMENT, while mariachi music floats on the breeze. Shoppers wander down the center of the road, glancing at ropas or zapatos, fluorescent toys and futbol T-shirts. In the distance there’s a crackle of rifle shots; no one looks up. And the smell of sizzling meat and corn masa coming from all directions forms a kind of taco fugue, hanging over this alley between rows of trees.

It’s a scene that happens a thousand times a day in some form, all across Mexico. But this isn’t Mexico. It’s the Chicago suburbs, unincorporated Kane County between East and West Dundee—a little past Medieval Times, the same exit on I-90 as Santa’s Village. This “Tianguis,” or Mexican market, is hidden in plain sight along the Fox River, between forest preserves and the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation (that’s where the shooting is coming from—wealthy club members picking off clay pigeons).

It’s on the grounds of a once-famous country getaway for folks in the city, The Milk Pail. Few of the Anglo residents of this neck of the suburbs, who often have fond memories of visiting The Milk Pail with their grandparents for Sunday dinner in the 1960s or 1970s, even know of the existence of the Tianguis. There’s almost no trace of it at all on the English-language internet, save for a couple of articles about NIMBY complaints in local papers.

Yet thousands of Latinos from all over the region, coming from as far away as Wisconsin or Rockford, descend on it every weekend. More than a hundred vendors, including about 40 stands offering different Mexican foods, set up shop every Saturday and Sunday, and promoters stage outdoor parties with Latino bands flown in for the occasion.

It’s the story in miniature of Chicagoland’s evolution from a midcentury dominant-white culture to one with a heavy Latino mix. The sort of thing that seems to happen by accident all over the region—an area loses its original population, Latinos move in, and entrepreneurial activity sprouts in all the empty spaces. The story of Pilsen, of Little Village, of Blue Island, of Aurora—all places where the local food culture is really two cultures.

Except this ramshackle, hopping market wasn’t anybody’s accident. It is, to borrow a phrase from the developers who built the suburbs all around it, a planned community.

El Tarasco

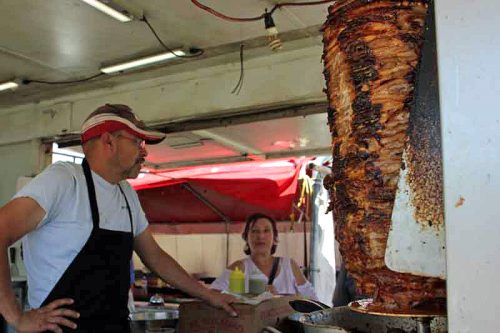

BUT LET’S START BY WALKING THROUGH the market on a weekend. I snag the last gravel parking spot by the fence and walk toward one of the first stalls, a battered red truck where the owner is tending a pastor cone, zebra-striped with crispy bits and freshly shaved strips of marinated pork. Next to it is a big white tent set up with tables. This is El Tarasco, seen on the cover image at top.

My son and I order two steak tacos and, for something different, a taco called El Phantasma, pastor with a spicy salsa. “It’s really spicy,” the young woman taking our order warns.

“That’s okay, I like spicy,” I say. Can’t show fear. Our tacos come—and El Phantasma has a brick-red salsa smeared all over it, with visible seeds. The color of pavement after you’ve skinned your knee on it. It looks like Death warning me away. I do not listen.

One bite and I’m sucking down canteloupe agua fresca for the next ten minutes. “It’s too spicy for me,” the woman observes offhandedly, about seven minutes after it might have helped.

El Tarasco is run by Sacramento Delgado and his wife Lourdes, from Elgin, I learn as he good-naturedly busts my balls over my failure to eat El Phantasma. They don’t have a standalone restaurant, but besides being at the Tianguis on weekends, they do catering in the area out of the truck. I ask him where he learned to cook. “I took a class to learn the basics,” he says. Which in his case, are an expertly managed trompo of pastor meat (“It’s cronchy,” he says, exaggerating his own accent), asada (steak), cabeza (steamed head meat), as well as housemade salsas, the main one being heavy on pineapple. He says he likes spice—in fact he points to a planter at the edge of the tent. “I’m growing my own ghost peppers,” he says proudly.

We take the paved walkway that leads deeper into the market. A stand labeled “Cremeria” is selling Oaxacan cheese as well as nuts, tamarind pods and other Mexican specialties; I talk to the worker there for a moment and it turns out to be an outpost of a Mexican dairy store I’ve seen on 26th street in the city, Cremeria Santa Maria. Apparently it’s worth it to trek 40 miles out here and spend all day in the sun.

I see more stands with pork stacked on plump, crispy pastor trompos—there are nearly as many in operation here as there are in the entire city of Chicago. Of course, in a competitive place like this, with sizzling pastor cones all around you, you’d never get away, as taco stands in the city do, with frying it up in a skillet. I stop at another stand run by three women, called Dina’s Tacos, and order another pastor taco.

Dina’s Tacos

Dina Prado is also from Elgin, and she doesn’t have a restaurant—”But I’m looking,” she says. She says she learned to cook taking cooking classes in Michoacan. I ask her why she started a stand here and she laughs: “Because there’s a lot of people here and I want to make money!” She says she actually started at the Tianguis selling tires, but got tired of carrying tires around, so she started a restaurant instead. (There’s a metaphor for Michelin in there somewhere.) “I want the people to know me [here], so when I get my restaurant, they’ll know who I am,” she explains.

Making fresh tortillas

Fashion

It mostly seems like big stands serving the same sort of tacos at this end, so when I spot a tiny stand advertising an eclectic mix from quesadillas to caldo de res (beef soup), I decide to check it out. Antojitos Buena Vista is run by two sisters, working off just a home electric griddle. Me, a white guy clutching a camera and asking her questions—it doesn’t take long to get in return the question I’ve been expecting someone to ask me: “Are you an inspector?”

I promise her I’m not, and hope that happily eating her food will satisfy her. She answers my questions regardless. Her name is Elena… something; she spells it for me three times but I never arrive at anything that remotely sounds like the way she pronounces it. (Her sister is Doris, and she’s visiting from Guerrero.) She has a job during the week, but she comes out on the weekend and sells her food; whatever she doesn’t sell, she eats during the week, which maybe explains the eclectic mix—she’ll have choices at home all week.

“Are you sure you’re not some kind of inspector?” she asks as she serves up a gordita with chorizo and potato.

Beer garden with live entertainment

This stand, Hernandez Tacos, which serves tacos al vapor (steamed beef) from a truck into a tent, has the longest line.

Besides food, of course, there are things to drink—a couple of places sell beer, many places have different flavors of agua fresca, from limon to fresa to tamarindo, and I’ve seen big jugs labeled “tepache,” the lightly alcoholic (about as much as kombucha) homebrew made from pineapple juice, which city inspectors tend not to notice in Latino neighborhoods in Chicago, at least. And there are examples of wild fruity excess, usually advertised as something Loko, like the one with Monster energy drink in it, the Monster Loko, that I see advertised around at three or four spots.

But then I also see a sign offering pulque, a more potent brew made from fresh agave, which has a famously short shelf life (though to my mind, fresh and spoiled pulque is a matter of degree of stinky foot smell). For that reason all you ever see in Chicago is canned pulque, which pulque afficionado David Hammond considers inferior. I step into the stand advertising it, Los Mixiotes, and order the house specialty, lamb birria.

Lamb birria, before dressing it up

Los Mixiotes is the first one I’ve found that has a restaurant in the city—I don’t know it, at 6532 S. Pulaski, but I earn a little credibility with owner Albaro Hernandez when I recognize that it must be just down the street from a branch of Zacatacos. Hernandez says he started coming out here on weekends because “I got a lot of customers from around here, they go to Chicago and they tell me, why you no put a little business right here?” He serves all the usual things, but lamb is his specialty—”For three generations, my grandfather, my father and me, we cook lamb. I sell in the flea market in Mexico City.”

I ask him about the pulque and he points to a Gatorade-branded cooler with a spout. “You bring that up from Mexico?” I ask.

When you go to Cabo San Lucas, a lot of people go to the shopping area. Not me. I go where the people live. In their backyards, in their garages, this is what’s there.

“Somebody brings it up,” he says. “I make it this morning,” he adds. I ask if it’s popular. “Ennh, some people like it, some people don’t like it. It’s like a beer, some people like it, some people don’t like it.” Then in case I’m not mystified enough, he says, “I don’t serve alcohol.” He says the word like it’s a name, Al Cohall. “The pulque no got alcohol. I make it from fresh fruit.” I’m completely baffled. Eventually I think he’s saying he gets concentrate, and makes it palatable with fruit flavors—but honestly, I have no idea what the precise truth (is there non-Al Cohall-ic pulque?) might be.

Like any Mexican market, the Tianguis has its mysteries, which it does not always give up easily.

Courtesy Chuck Engels/Cvillememories.com

Courtesy Chuck Engels/Cvillememories.com A HUNDRED YEARS BEFORE IT WAS a Mexican market, before it was even The Milk Pail, it was The Country Tea Room. Which brings us to Max McGraw.

Max McGraw built a fortune in electricity in the early 20th century. Besides supplying power, and the equipment that was needed to supply power, he also sold things that would use power—like a device that would take two slices of bread and toast them, to a preset level, with no danger of burning it like your Irish maid Bridget always did when she held it over the stove. He called it a Toastmaster. Hold that thought.

In 1926, wealthy Max McGraw bought a dairy farm along the Fox River. He liked to hunt, so eventually he bought more land and established a private game hunting club adjacent to the farm, too. But he knew that besides electricity, there was another thing the newly prosperous middle class of the 1920s liked to do: drive their shiny new Ford automobiles. But where could you go with a family?

So he opened a restaurant in the country on his farm, called the Country Tea Room. Today, with cars that zip down superhighways, you can pop out to unincorporated Kane County in about 40 minutes. Back then, it was more like a couple of hours at 35 mph, even with ultramodern two-lane Route 25 newly built, so you tended to make a whole day of it—lunch at the Country Tea Room, let little Johnny take a pony ride, feed the ducks, pet the goats, do some shopping.

Pony ride. Some things never change

One feature of the Country Tea Room in particular stood out—at every table you had your own Toastmaster toaster, where you could test out modern, automated toasting for yourself. Say, Mabel, if I can make my dress shirts last all winter, dontcha think we could afford one of those Toastmasters…

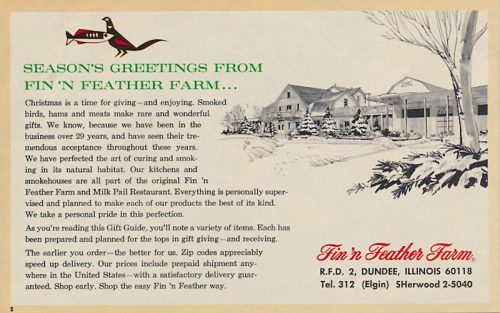

McGraw shut down the working dairy farm in 1939 and in classic agritainment fashion, reinvented the farm as the farm-themed family fun center The Milk Pail, which had at different times a diner, a bar, banquet rooms, and shops, and was also the home of another business, The Fin ‘n Feather Farm catalogue, which smoked game meats and sold them all over the country. In an unusually charming example of corporate synergy, the testing process at Toastmaster went through 1000 loaves of bread a day, which went straight to these properties to feed the wildlife in the wetlands. And much of that wildlife would then be smoked right next to where El Tarasco stands now, to become Fin ‘n Feather Farm mail order goods.

Page from a 1960s Fin ‘n Feather Farm catalogue

McGraw sold the property to his son-in-law Ed Eichler in 1956, and died in 1964. The hunting land became a separate non-profit entity, the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation, but the Milk Pail continued well into the 1980s as a country restaurant getaway, remembered to this day by residents who grew up around it. Just don’t ask them when the last time they went there was.

Bruce Oehlerking

IT TOOK ME A WHILE TO GET hold of the current owner of The Milk Pail—or even to figure out who that was. And in the meantime, after three or four visits, I thought I had it all worked out. The declining property was owned by a developer in the western suburbs named Bruce Oehlerking, and it seemed pretty obvious that he was simply keeping a little cash flow flowing by renting space to Mexican vendors, while he waited for the housing market to turn to where he could bulldoze it all and make a suburban housing development out of it—Milk Pail Pointe. The Mansions at Seau de Lait.

Then I actually met him. “I’m not building any more houses,” Bruce Oehlerking said, firmly.

Oehlerking is a fit 77-year-old (he credits two new hips and the resulting abandonment of his previous bad habits), in sunglasses and a Crocodile Dundee hat. Beneath a gentle manner, you sense the force of personality you expect to go with building and selling housing all over the western suburbs and the country—he figures he’s built about 2000 homes from here to Florida, plus shopping centers and more.

“I’m not building any more shopping centers. I’m building apartments—because, my opinion, that’s how we as a society are going to start living more. I’m building nice apartments. I’m giving them a 1250-square foot, 2-bedroom, 2-bath, elevator, 2-car garage for $2000 a month. Why be committed to a home—especially empty nesters and young professionals? And all those homes I built—young people don’t want them. The dream has changed.”

Not that this has much to do with The Milk Pail, except by way of showing that Bruce Oehlerking does things his way, and it’s not all about heedless growth and suburban sprawl. He first made his name locally when he and a partner developed an outlet mall in a former piano factory in St. Charles. For their next outlet mall, they acquired the 22-acre Milk Pail property from Ed Eichler’s heirs in 1985, building new retail buildings with a comparable old-fashioned flavor to house outlet tenants.

What follows is a history of riding booms and busts. “Sears came in [to Hoffman Estates], and all my outlet tenants who sell to Sears went bye,” moving to Sears’ retail developments. In the 1990s he had a good business doing corporate picnics on the property—until the dot com crash in 2000 cut all that back. He continued to run the restaurant and banquet hall, doing 100 weddings a year, but dining habits changed—”Fine dining out in the country? Not gonna happen. You and I don’t take the time. The fast foods and the delivery are dominating our food habits.” So he closed the restaurant.

El Gran Paseo divides Fin ‘n Feather’s factory barn from the short-lived outlet mall

On the up side, a new exit on I-90 makes the property more accessible than it’s been. “They built it for me, you know,” he says. “So now my market, from Rockford to Chicago to Wisconsin, can get here really quick. They really did a nice job, and I want to thank the government for doing that,” he says with a grin.

So where does the Mexican market enter this story? We come to the habits he took up when he gave up his old habits. “I’ve been fortunate, I’ve traveled all over the world. I’ve played golf all over the world,” he says. “If you go through Mexico, most cities have an open air market one day a week. Like in Guadalajara, right downtown, they have the biggest tianguis you’d ever want to see.”

If Latinos are invisible for many suburbanites, they’ve never been for Oehlerking. “We were vegetable farmers, where Woodfield Mall is now, and when I was ten years old, it was all hand labor, and I ran a crew of Hispanics,” he says. It’s clear he responds to the family-oriented culture, the work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit. “When you go to, like, Cabo San Lucas, a lot of people go to the shopping area,” he says. “Not me. I go where the people live. In their backyards, in their garages, this is what’s there. This is exactly what’s there.”

In short, a man was bitten by a bug, to create a space where Mexican entrepreneurship could blossom, and he had the place to do something with it. “We started in 2012, with six vendors,” he says. “Each year we’ve built it up, and built it up, and now we have over 100 vendors. We have 40 some food vendors, all licensed by the county. We have a liquor license that covers the entire property.” (So tepache and pulque are okay.) He shrugs. “It’s been fun.”

The Garden Room in The Milk Pail, set for a wedding

The Tianguis, which seems at first glance like an afterthought at the back of the property, is actually key to his plans to spruce up the property for two markets in the future. One has to do with how wedding culture has changed—people want funky places like barns and industrial spaces, and interesting food. Well, he has an old barn and industrial space, the Fin ‘n Feather Farm plant, that he’s redeveloping. And he has Mexican food vendors lined up for you—why eat rubber chicken when you can eat authentic birria?

The other is, again, corporate events—”Teambuilding. You rent the place for the day, and you can have anything you want—games, amusements, music, food.” You can bring in outside catering, anything you want, but the Mexican vendors will be the easy default option for planners, because again, who doesn’t like tacos these days? “And I sold the property last November—”

WAIT. WHAT?

“I sold it to Juan Ibarra and his wife Maricela,” he says. “He owns a big concrete firm—he does concrete for 800 homes a year.”

THE WHOLE THING?

“I sold it to them, and they hired me back as general manager for five years. Together, we’re building it up again,” he says, and smiles.

Gallery: Making a Monster Loko at Chelicas

Sweet-spicy drinks inspired by the mangonada are all over the Tianguis. One helado stand, Chelicas, shows us how they do it.

Juan and Maricela Ibarra

WALKING THROUGH THE MARKET WITH Bruce Oehlerking is like watching a lord walk through his village—”Mr. Bruce,” they all call him, and any effort to pay for what we nibble along the way is rejected so firmly that I soon stop trying. Never mind that, as I just learned… he doesn’t own any of it any more.

But when I meet Juan and Maricela Ibarra, the well-appointed couple who bought it less than a year ago, I know that they’re the owners but Bruce is still, in some sense, running the show. Certainly he’s his own boss since, as he points out, he’s not in a line capacity, he doesn’t report to anybody. He just does what he sees needs to be done.

What he’s really done is find successors who will keep his dream alive—a Mexican couple who, like him, have the revenue from other construction projects to take the long view on the property, and like the idea of this Mexican market incubating businesses and conveying Mexican culture. Even in the short time I’ve been coming here, I can see that they’ve provided an infusion of capital and labor that has given some of the old buildings a needed freshening up. (The new concrete work on El Gran Paseo is quite nice.)

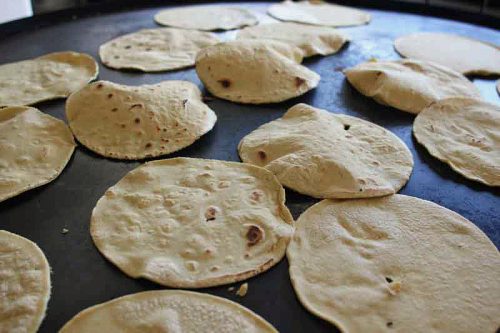

Tortilla machine at Don Rafa

Working our way through the Tianguis from a different angle, we stop at a stall called Don Rafa, which has the best bit of gadgetry on the premises—a large comal for frying tortillas, and next to it, a device with a grinder and a conveyor belt, which rolls out masa like a ribbon of pasta and punches out a circle, which Don Rafa Nuñez himself grabs and flings straight onto the comal. What’s left falls into a bucket, and then you can feed it through again—since it’s not wheat flour, it has no gluten, and thus doesn’t toughen up with repeated working. Compared to the handpatted tortilla restaurants, they’re able to crank them out, and in fact sell them in bulk to other vendors here. Want some to take home? They’ll be ready in one minute, as many as you need. (It’s kind of like having a toaster at the table.)

The Nuñez family and Bruce exchange hugs, and then we sit to grab a bite. “We’ve created over a hundred businesses here, more than 600 jobs,” he tells me. Looking at the Nuñez family as they hustle to serve their customers together, he says, “This is what it’s about.”

We walk back from the market, past a building presently used for a Mexican Bingo-like game, with numbers painted on the walls. “The challenge,” he says, “is to get people to get out of their house, when you have Amazon, and every food vendor of the world with your iPhone, saying bring me this, bring me that. You don’t ever have to go out of your house. So what we’re providing people is a reason to come here—the experience.”

So for seven years he’s been growing an experience here. It’s getting ready to offer the world something you wouldn’t expect to see in the suburbs—”My motto is, come experience a taste of Mexico, from the culture to the language to the music to the food. I want to make it a destination in this part of the country, the real taste of Mexico.”

Bruce Oehlerking

We think of suburban developers as guys who tear down the last truffula tree, to put up more prefab houses. But Bruce Oehlerking is like a Lorax of tacos, preparing a field for Mexican businesses to grow. As if to endorse the somewhat strained Seussian metaphor working itself out in my head, he points out a huge oak in the middle of a scraggly patch of grass.

“See that oak? It’s about a 200-year-old oak, it was going to come down for parking,” he says. “All this is going to be for handicapped parking. But that baby’s stayin’,” he says.

We stand looking at it, and digesting. “I’m having fun,” he says. Then he seems to emphasize the next sentence, as if he’s revealing something kind of important, like the secret of his life.

“I make things happen,” he says.

Michael Gebert is el patron of Fooditor.

To find the Tianguis from Chicago, take I-90 west to exit 56, IL-25. Follow the signs north toward Santa’s Village, until you see the Milk Pail complex. The outdoor market is open weekends only through the end of October; a smaller market will be in tents on the premises until April.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.