WE HAVE A CERTAIN IDEAL OF FISH in restaurants—the pristine white fillet that tastes as clean as a rushing mountain stream, prepared delicately to a mouthwatering flakiness. Not too much of anything—cooking, seasoning, fishiness; it tiptoes up to what it is, by nature. The restaurant that gets this right—produces crispy skin over tender, moist flesh, fillets Dover sole at tableside, serves perfect slices of meltingly soft crudo—rates highly indeed.

But needless to say, there’s more than one kind of fish in the sea.

“Some of the dishes that we have on the menu, they’ve been around for hundreds of years,” says Marcos Campos, chef of Porto in West Town. “Like fishermen used to make in their boats, when they were out. I’m trying to bring those flavors to Chicago, but it’s a really big challenge because we’re in the middle of one of the biggest countries in the world.”

Chef Marcos Campos of Porto

Porto, which opened in December, is the newest restaurant from Bonhomme Hospitality Group, which has Beatnik next door and another Spanish restaurant in Black Bull on Division (where Campos is also chef). Black Bull has a considerable seafood presence on its menu, including conservas, high quality canned fish imported from Spain, usually served simply on toast as tapas. Porto has the same psychedelic, an-antique-store-exploded aesthetic as other Bonhomme restaurants, but its focus on high quality seafood from the Atlantic coast of Spain and Portugal is more serious than the group’s other restaurants have been—a conscious effort by both Campos and owner Daniel Alonso to bring the best of the region to Chicago.

“When I went to Galicia with Dani and we started eating in restaurants and going to the fish markets, and even eating in little small restaurants run by grandma, we were like, this is amazing,” Campos says. “I’m from Spain, from Valencia on the Mediterranean coast. They’re trying to hide the flavors of the protein. In Galicia, they don’t want to hide anything, they don’t want to use too much seasoning, too much oil, too much butter. They want to let it be the way it is.”

That sounds like a minimalist approach to seafood such as you might find in many different kinds of restaurants in Chicago. But it can also lead to strong and powerful flavors—that come from the sea, not a seasoning. One example Campos gives is of cooking with squid ink—I end up trying a dish called Choco da Ria, sepia and potatoes in a cuttlefish that he compares to Mexican mole, thick and black as tar and deeply funky like blood sausage. These are sea flavors that are anything but delicate.

“The whole idea of Porto is bringing fresh seafood from Spain or Portugal—the northern Atlantic part of Europe.” Campos explains. “Because we believe that it is the best quality we can find for fish. Nothing is farmed, it’s all wild. So we can taste the flavor, we can see the color of the fish, that is nothing like you’ve seen before.”

I think people have the idea that a seafood restaurant is always about lobster or shrimp, and we are totally different. We don’t even have those items on the menu.

The menu is rooted in Galician and Portuguese cooking—”80% Galician”—and wine culture. “When we first had the concept, we thought, somehow we’ve got to bring the product from Spain.” he says. “We’re not going to be able to make it authentic with those flavors if we don’t get the produce. So then I start talking with fishermen over in Galicia, saying, did you guys ever think about sending fish to the United States? ‘Oh, we are trying’—actually that’s how the Spanish people are, ‘Oh we are trying, it’s okay, we’ll take our time.’ No, we’ve got to make it happen in the next two months, we’ve got to have your fish in Chicago on a weekly basis. Doesn’t matter how, but let’s do it.”

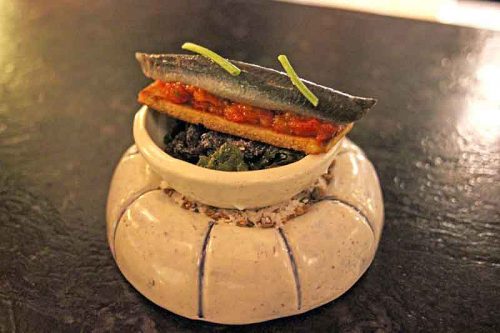

Boquerone (white anchovy) on pickled tomato relish, puffed garbanzo chip

In the end, he wound up working with Regalis Foods, a Chicago-based importer that has long experience with Spanish foods as an importer of jamón ibérico de bellota, the highest grade of Spanish ham. (Fooditor wrote about Regalis here.) In fact, he claims Bonhomme Hospitality is now the largest single account for fish from Spain in the U.S. “It’s a big challenge, bringing the fish, making sure it’s preserved the right way, and also teaching people what a John Dory is, what a turbot is. I think people have the idea that a seafood restaurant is always about lobster or shrimp, and we are totally different—we don’t even have those items on the menu. There’s a lot more in the ocean to offer than those five ingredients that everybody thinks about.”

Porto, which has turned an anonymous bank building into a Galician visual riot, has two dining rooms. The back, where we start our conversation, is the former parking lot, covered over for winter but able to be opened to the outdoors in Chicago’s few temperate months. Fish scale tile on the walls and lamps made from hanging fishing baskets carry the theme, but the main point of interest in the room is a wood fire stove—all cooking is done over live fire here, over charcoal, wood or a Japanese binchotan grill.

Slicing jamón ibérico

The front room, the onetime bank, has coolers full of Spanish and Portuguese wine along one wall, and above the bar—where cooks slice jamón ibérico and serve you seafood tapas—a metal rack holds hundreds of small canned conservas. Canned fish might seem a comedown from fresh fish, but it has an honored place in Spanish cuisine—”You open the can and it’s just beautiful, even better than the fresh fish that you can find in any market in the U.S.,” Campos says.

“Everybody’s talking about conservas now,” he says. “But I don’t think they’re respecting it, the way they should be doing it. They think conservas are something cheap and humble—the chicken of the sea, that you can find in the market or they put in the salad bar. I wanted to have razor clams, mussels, but I couldn’t bring fresh mussels to a restaurant, the moment they get here, they will not be good.” So top quality conservas are the answer—”Every time you open it, it’s going to be the same size, the same seasoning, the same quality.”

Jamón ibérico de bellota

Campos already used conservas at Black Bull, from a high end brand called Ramón Peña, but for Porto, he went up a step to the same company’s premium line, called La Brujola, which preserves the catch from the peak season and only picks the top grade of visually perfect product. Before they opened, they ordered 5000 cans, to last the first six months of the restaurant.

But conservas are not the only way that Campos seeks to ensure the quality of Spanish fish in the middle of North America.

MARCOS CAMPOS GREW UP IN HIS father’s butcher shop—”When I was 13 years old I started working for him, and by this time there was a little movement toward dry-aging beef for 10 days, 15 days. My dad wanted to see what was going on. It was always in my head— one day I want to run a dry-aging program instead of just getting it from a farm. When someone else gives it to you [dry-aged], you don’t really have control.”

Dry-aging programs in the U.S. that I’ve seen simply set aside a part of the walk-in meat cooler, utilizing the same temperature and humidity as the overall cooler to draw moisture from the meat over time. In Europe, though, Campos had seen dedicated dry-aging coolers which allowed you to select the precise temperature and humidity level with the press of a keypad. He explains the purpose behind this: “Dry-aging is a process where you control humidity and temperature to make sure the muscle is getting more tender and more concentrated. At the end of the day, any protein that is meat or fish is made from water. The more water you eliminate from the protein, the more concentrated the flavor’s gonna get.”

Three years ago, at the National Restaurant Association show in Chicago, he saw what you can safely call the Porsche of dry-aging. A German company called Dry-Ager, started by two brothers (one with a culinary background, one with an engineering background), was showing off its state-of-the-drying-art equipment, which it saw as aimed strictly at the high-end steak market—right under the logo, it states “Built for beef.”

Whole John Dory and turbot in the dry-ager

And to some extent, that’s what Campos saw as the natural use for it, too. “When we opened Porto we said we were going to have one meat on the menu, a really good steak from Spain that we call vaca vieja, a really old cow. They’re really big steaks but beautiful. But they’re impossible to [import] in the United States right now. So I have these dry-agers, somehow I gotta start using them.”

How he got the dry-agers was that he started talking to the company representatives at the NRA show about something they hadn’t thought about—using them with fish.”They were so excited they were like, okay, we’re going to give you one, that way you can start experimenting with whatever you want,” he says. “From the beginning I told them, I don’t want to do what everybody else does, I don’t want to put a whole ribeye in there to see what happens. I know what happens, everybody does that already.” So they made him a brand ambassador for seafood, with two of the dry-agers—the only other two in the U.S., so far as he knows, going to a brand ambassador for meat, Rob Levitt of Publican Quality Meats.

Dried monkfish skin—”We know every bone, every piece of the fish,” Campos says

But to come back to the opening point about fish—does anyone want it aged? Don’t we want it as fresh out of the sea as possible? Not necessarily—besides the concentration of flavors effect, a judicious amount of preserving on site at Porto aims to deliver a fresher tasting quality of fish to diners. Particularly at a restaurant which gets fish twice a week from Spain, and has to make them last for a week.

“We clean it, remove the insides, and then dry-age for at least 24 hours,” Campos explains. “What happens in those 24 hours, creates a surface on the outside of the fish that is protective of the meat, not letting bacteria get inside.

“The first fish we put in [the dry-ager] was a turbot,” Campos says. “Turbot has a lot of gelatin, which is like the fat for an animal. We leave it for two days and we discover that dry-aging the turbot, you will get more crispy skin when you cook it, but also the protein became really meaty. When you cook a fish, normally it becomes flaky, breaks into little pieces.”

For a fish like turbot—a round, thick fish that looks like a porterhouse steak with fins—just a couple of days in the dry-ager (we’re not talking 45 day dry-aging, like with steak) produces something with both superior taste and texture, and a longer-lasting product that ensures top quality the whole time it’s used in the restaurant. “We had a turbot that we aged for four days, and it was still good after 12 days.”

Fish parts

Campos is experimenting with more than just whole fish, though. In one of his two coolers, which sit quietly in one corner of the back dining room, he has a whole Frankenstein’s lab of parts under the cooler’s UV light—a tray of mussels, whose concentrated flavors will be added to stock and used in a mussels carbonara. Tuna belly (from Japan, a rare exception to the Spanish purchasing model) is wrapped in Spanish seaweed. Monkfish roe sacs sit open on a shelf; other pieces are buried in salt and herbs.

One thing I quickly note is that it’s not much product relative to the size of the restaurant. But it’s reflective of the Spanish tapas orientation—no one is eating a big filet of turbot, many people are eating a little bit of turbot in a composed bite.

It’s also reflective of the whole idea being basically experimental. Armed with a popular fish cookbook from Australia—The Whole Fish Cookbook, by Josh Niland, who runs a fish shop in Sydney and has played around with techniques for everything from dry aging to seafood charcuterie—Campos is experimenting with as many different ways to capture the flavors of the Spanish sea as he can think of.

“People are afraid of it, but smoking, curing, pickling— they are all techniques that have been around for hundreds of years.” he says. “But nobody wants to use them any more because they are using sous vide now. I believe in tradition, that those recipes need to come back.”

Other chefs might reach back into culinary history of 30 or 40 years to justify their point of view. Campos goes back centuries. “I believe that the culinary movements are a circle. It started on number 12 like 200 years ago with grandma cuisine—super-slow cooking, cooking over the fire, everything about the flavors. Now we are in the middle, at number 6, everything is about creativity, how to make a plate look beautiful. But I believe people are going to get tired and the circle is going to keep going all the way to 12 again, looking for those flavors from traditional recipes and cuisine that nobody wants to do any more, because they think that they’re too humble for the restaurants. I think it’s going to happen, and I want to be ahead of that.

“My personal goal,” he says, “is to show the people that we can make it, we’re going to make it here in Chicago, it’s a really big city with really great restaurants, we really want to be part of that movement of what Chicago can be.”

Michael Gebert is the big tuna of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.