AFTER OUR INTERVIEW, AS WE SHOOT A FEW PHOTOS, John Ross and Todd Stein let out a little more of how they feel about talking about Formento’s. Ross, co-owner of B. Hospitality Group, mentions a popular restaurant that opened around the same time, and says, “They’ve had six chefs in two years! And no one knows it, or cares.”

But that place is a small restaurant in a neighborhood, like Ross and B. Hospitality’s original restaurant, The Bristol. Formento’s is on Randolph, the main stage of Chicago dining, and bringing in your third chef in two years—after opening chef Tony Quartaro (now at Dixie) and a brief stint by Stephen Wambach (Epic)—is inevitably going to draw attention in the hothouse of food media. Ross continues, “People ask me, how do you know Todd is going to stay put?”

“Try me,” Stein says, a big grin on his face. He too has been visible for changing venues as well as what he did at them, since he came to attention with Cibo Matto, an acclaimed but short-lived Italian restaurant in the Wit hotel. Since then it’s been The Florentine, Piccolo Sogno Due, and stints with restaurant groups in Chicago and Atlanta, in particular focusing more on working within a multi-restaurant environment opening new restaurants, most recently in Chicago for the 4 Star Group (Crosby’s Kitchen, Remington’s, Frasca, etc.)

But he and Ross are convinced that this is The One, a natural fit between a big restaurant—which has remained popular through its evolution—and a chef searching for the right place for what he’s best at. I met with them in a second floor private dining room—it’s a big place with many nooks and crannies—and we talked about what it’s like reinventing your restaurant in the public eye, and why they think this version of Formento’s will last.

John Ross and Todd Stein

1. “The first day I got off the train, I was like—yeah, this is it.”

FOODITOR: Let’s start with Todd. How did you come to Formento’s?

STEIN: I think it’s a lot of years of friendship with John and Phil [Walters, also co-owner], being of like minds, never really talking about doing something together—

ROSS: Going to dinner—

STEIN: John was asking me my opinion of other chefs in the city they were looking at, and as I was offering my opinion at some point—well, I know exactly where I was, I was sitting at Frasca, and we’re texting back and forth and he says, “What about you?”

And I said, uh, I didn’t even think about that. Finish your business with these other people you’re talking to, and if it doesn’t come to fruition, I’ll consider it then.

ROSS: Actually, we were having dinner a few weeks prior, and we maybe had one or two too many glasses of wine, and we played around with it then, but just as a coulda-shoulda-woulda. This should have been the restaurant that we opened with you in the beginning. It would have been the perfect fit from Day 1. But I think you were in Atlanta at the time—

STEIN: I was just coming back.

ROSS: But you’re here now, and we’re moving it in the direction which we both want it to be.

STEIN: I wasn’t looking to leave then, I learned a tremendous amount [with the 4 Star Restaurant Group] about things I never would have before in that position. But I looked at this opportunity not as a return to the kitchen, but as a return to the path that I started on at the very beginning of my career.

Which is Italian food?

STEIN: Right. Italian food came to me later in my career, but it is what I think I do better than most other foods, and it’s what I’ve gotten the most recognition for. It’s really the food that is truly in my heart. Opportunities like this don’t come along all the time, especially with people that you’ve known for a long time, and have tremendous respect for, and you have like minds with about running a business, not necessarily just about the food. All of those things—I couldn’t pass that opportunity up.

So you didn’t start by cooking Italian food?

STEIN: I had cooked contemporary American food until Cibo Matto.

ROSS: But don’t you think, if I may interject, that even at MK you were cooking Italian-French—

Formento's

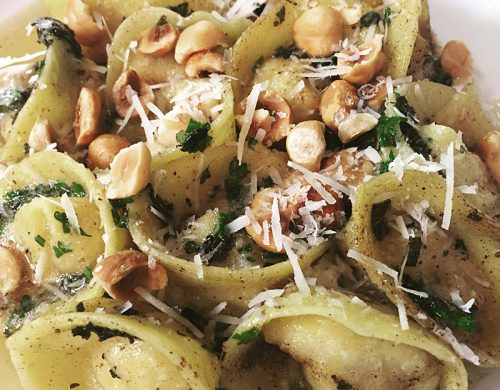

Formento's Orecchiette with kale and walnut pesto

STEIN: Italian was always in the mix. In 1995 I lived in Paris for six months. And my sister and her husband were living in Bologna, Italy. And so I went to see them. And the first day I got off the train, I was like—yeah, this is it.

I was still in culinary school at the time, I was working at Gordon, and so it had a really profound impact on me as a cook, it always would show up as a chef. They were twists on Italian, but it was really the mentality of treating ingredients lovingly, minimally, and allowing them to shine for themselves, plus cooking regionally, that kind of became my mentality as a chef.

So it always there, and Cibo was my opportunity to let it shine. Which I think was pretty impressive—I mean, I still get people saying what a great restaurant it was, and it was such a shame what happened there. It was any of these restaurants, before Randolph Street.

ROSS: I think that when you look at chefs, there’s a vast array of chefs of different talents, obviously, but the thing about Todd is, Todd makes really delicious food, but he’s a businessman, too. He really understands the front as much as he understands the back. He understands wine, he understands cocktails, he understands service—

STEIN: Thank you, Michael Kornick.

ROSS: Exactly. And Phil, having worked with Michael Kornick as well, we all kind of come from that same mentality. And running a lot of restaurants helps you understand something that’s big, but has a little sandwich shop [Nonna’s] and a lot of other things as well.

STEIN: I mean, this is basically a hotel, in the guise of a really pretty restaurant on Randolph Street. It’s all of these things and it’s being able to juggle all of these people to make sure it works. And I think running ten restaurants for 4 Star, or working in hotels or whatever, all of that culminates in doing this here.

2. “It’s a very personal restaurant—and that makes it hard.”

John, tell us how Formento’s got to this point. What was your original idea?

STEIN: Twenty seats? [laughs]

ROSS: Formento’s is named after my grandma, Nonna Formento, and when I was growing up as a kid, 5, 6, 7 years old, she lived with us. I’m from small town Iowa, outside of Des Moines, and on Sundays we used to go to my uncle’s house in the countryside, at 9 a.m. on Sunday, and by noon there’d be 50 family members, uncles, aunts, cousins, the whole shebang. And Grandma was in the kitchen, rolling meatballs, rolling pasta, doing everything by hand. And I loved it. I loved her anyway, but I’d gravitate to the kitchen and help her make things, and it brought you back to a time of just being very happy.

Also, then, my dad, who was a blue collar entrepreneur if you will, on Friday or Saturday we’d always go to dinner at an old school red sauce joint. Always. And I thought that after Bristol, after Balena, knowing that we were working on Swift & Sons and Cold Storage at the same time, we sat down and said, do you think Chicago would take an old school Italian joint?

The mentality of treating ingredients lovingly, minimally, and allowing them to shine for themselves, became my mentality as a chef.

We all thought that it would, and here we are. There’s things on the menu that definitely come from my grandma, like the chocolate cake, and the meatballs, and the Sunday gravy. And there’s pictures of my grandma and my family around the restaurant. It’s a very personal restaurant to me—and that makes it hard, sometimes.

But a lot of the Italian-American classics that were on the menu when you opened aren’t any more, are they?

ROSS: Well, the rigatoni, with the meatballs and sausage, are on the menu. Something that we always had growing up was a relish tray—I’d go to my grandma’s house when she didn’t live with us, and there’d always be something on the stove, and there’d be tinfoil over that or a lid on it, who knows what that is—and then there was always stuff out. Deviled eggs, and pickled this—she had a huge garden, and she’s the reason I’m in this business.

No, the rigatoni, the meatballs, the sausage with the meatballs, the cake [are still on the menu]. And Todd’s looking at other things too—we wanted him to get in, get comfortable, and do his food, but then the question is, how can the story of my grandma and him converge as well?

STEIN: We talked about this, that at one point you realized that this chef-driven red sauce Italian concept really wasn’t what people wanted—

Formento's

Formento's Avocado toast with crab

ROSS: I feel like in Chicago, people only want the old school red sauce joints. They’re going to go to La Scarola or Sabatino’s or various other places. And a lot of the food was a little bit heavier, especially as you get into spring and summer. So how do you combine the lighter style, or even the Cal-Italian style, with some of the red sauce classics that people crave, like chicken parmigian’ or the rigatoni meatballs?

Right, because you talk about her having stuff cooking on the stove, but Italian food today is the opposite of that, it’s not that kind of long braise with deep earthy flavors. It’s light and fresh—and closer to what Balena does, frankly.

ROSS: What’s funny is that when we first opened, everyone has their idea of what Italian food is, and then what Italian-American food is, and they really do this crossing of the lines all the time. We had a lot of Italian people come in, and they’d be like, I’m Italian and I know Italian food, and we had stuff that was much more Italian-American, 1950s, even early 1900s—and it just reminds me of Big Night—these guys are doing this beautiful Italian food, and across the street there’s the red sauce joint and the red sauce joint is killing it. Because that’s what the Americans wanted then.

You can do the combination of it. I think in Chicago, specifically, they want the chicken parmigian’, they want meatballs and this and that—but then they want the beautiful grilled lobster with fennel too.

STEIN: Well, look at how Sarah [Grueneberg] does it at Monteverde. There’s a few dishes that are old school Italian, and then her version of Italian. I do think in a city like this, it works.

3. “Neighborhoods dictate things.”

But still, you have a group that started out with restaurants that kind of unabashedly told people what they were going to eat. And now you have one where you’re changing it in response to the audience telling you what they want to eat. Was that a shock for you?

ROSS: We’ve evolved as the marketplace has dictated, to some degree. The Bristol was one of those restaurants where it was like, we’re doing this and you’re gonna like it. The Bristol, for Chris [Pandel] and Phil and myself, was a very selfish concept. We loved wine, we loved cocktails, we loved beer at the time, though none of us drink beer any more, I don’t think. And Chris wanted to be a kid in the candy store and change the menu every day. Fortunately, he’s such a talented chef that we were able to get away with that for such a long time.

It’s all about hospitality, but we had pig tail and pig head and bone marrow and all those things eight years ago, they’re not necessarily new to the United States, or dining in general, but it was new to Chicago. And it was kind of a selfish concept, but it worked. And that’s kind of the antithesis of what hospitality is, but at the same time, if you’re really streamlined, and you’re really focused on something that people know, then those people will come. And that’s what we had.

Balena, I think a much more accessible restaurant, we have pizzas and everybody loves pizza, we have pasta and everybody loves pasta, but then Chris, even at the very beginning, was doing tuna conserva, which not everybody understands.

Okay, the city doesn’t really want that. Well, we want to own our business so we have to evolve.

Neighborhoods dictate things, the size of restaurants dictates things, people dictate things. And we knew, getting into this, we wanted to be true to… my upbringing, I guess I’d say? But at the same time, we wanted it to be this bustling place all the time. We didn’t want it to be too fancy, we wanted it to be accessible enough, so we weren’t going to have a lot of crazy stuff on the menu—although Todd has pig ears right now, and they’re absolutely delicious. We had two little kids in the other night eating them like they were French fries.

I always wanted the restaurant to be fun, and convivial and enjoyable. Not overly complex or pretentious—

STEIN: Well, we took tablecloths off—

ROSS. And we bought wood tables, because tablecloths seem fancy and it was never supposed to be that. It was an homage to the history of an old school Italian joint which was tablecloths and black bow tie. But people felt that it was too stuffy. It was never supposed to be that way.

Did you buy new tables for the whole place, just now?

ROSS: A few months ago.

Yikes.

STEIN: Well, it happens.

ROSS: And we’ve seen the effect of the changes. It’s a much younger clientele now, than it was in the beginning.

STEIN: More to come, we’re going to work on Nonna’s next, more, new different sandwiches and salads. Make it more of a place to hang out.

Bucatini carbonara

ROSS: We have something that we’re playing around with where maybe Todd can do a chef’s table at night as well.

STEIN: People said to me when I was coming here, “Oh wow, third chef in two years, you’re crazy.” And I was thinking, look at Gordon. In 22 years, there were 16 chefs. The restaurant never changed, but the concept changed, and the food changed with the chefs. I think that’s okay. I think we’ll find that some things will stay, and some things will go. But the restaurant has evolved with the city since the beginning two years ago to where I think it really needs to be.

I thought when they opened that the food was executed in the way that it was supposed to be—I ate here a lot, I was a guest here a lot. I thought it was really cool. Lots of cool things that you don’t think about, like eggplant parm, or the scampi, or the relish tray.

But okay, the city doesn’t really want that. Well, we want to own our business so we have to evolve. As every restaurant does. Okay, it evolved maybe a little quicker than it should have, two years. And then there was the bridge with Stephen, who set the table for what I wanted to do, which was tell people that it’s okay to change. It doesn’t have to be red sauce. They’re really cooking good food.

4. “He’s having fun.”

Okay, we’ve talked about how you both got here. Let’s talk about what you’re putting on the menu.

STEIN: I think it’s funny because a lot of people have said to me, are you going to put all your classic dishes on the menu? And I say… no, I’m sure that carbonara will show up because it has to. But I’ve evolved as a chef, and the city has evolved, since Cibo Matto. The paccheri that’s on the menu, the squid ink pasta, is a variation on one that I did before, and it’s evolved itself.

But that’s really about it; the rest of the menu is primarily new—

ROSS: If I can, I posted something on Instagram the other day that—he’s having fun. That’s what it gets back to—you’re having fun here.

STEIN: I’ve never constantly thought about food more than I am right now. I got home last night and I was thinking about stuff, and it was like, here’s two more dishes that I could do. If I could, I’d put them on the menu today—but then we’re going to have a menu that’s too long.

There may never be a wholesale menu change at this restaurant again, where top to bottom we start over. But every couple of weeks—two dishes here change. And in another couple of weeks, two more. Now there are things that stay on the menu, there are standards. But to me, at 45, to have this much fun—I never thought it’d be possible. And it’s not like, you start a new job and you love everybody and everything’s great—I know the difference between that.

We have investors who, the first couple of weeks I never saw—now we see them multiple times a week.

ROSS: Four tables last night.

What are some of your dishes that you think really sum up your approach? You mentioned some of the ones you brought back—

STEIN: Yeah, we don’t need to talk about the carbonara [laughs].

Lightness, and flavor, are the most important things to me. Take the calamari. You go to an Italian restaurant, and you get the calamari, and it’s a plate that’s loaded like this, and sometimes it comes with mayonnaise and sometimes it comes with red sauce.

So I wanted the batter to be lighter, so I used rice flour, and it gets a really nice crispness. This will lead to something else afterwards. But we’re doing it as a snack, very small plate—

ROSS: Hopefully you’re having an aperitivo, something to eat while you’re deciding—

STEIN: And then, if you have Federal Hill calamari, you have pepperoncini. So why don’t we combine the aioli and the pepperoncini, to dip the calamari in. So you get this really nice and crisp calamari and you go, wow, that’s got a great crunch, it’s not overcooked, it’s got a great texture, and you’ve got this really nice sauce.

So then I was sitting there two days ago thinking, I wonder what else you could fry in the rice flour batter? So I cut up some onion and dipped it in the batter. It was like eating onion glass. The batter took to the onion unlike anything I’ve ever seen. And I think, okay, that’s going to come in play somewhere, someday.

So, you take fried calamari and—I don’t want to use the word “elevate,” but make it more fun. That would be one thing. Another, the cauliflower dish that we’re flash frying. I hate to be talking about fried food two in a row, but it’s got preserved lemons, and it’s got chiles, and it’s got soppressata, and when you toss it all the heat from the cauliflower releases the fat from the soppressata, and you’ve got all these great umami-like flavors going on at once. It’s unique.

I thought the paccheri was interesting because it’s kind of a down and dirty dish, like puttanesca—

STEIN: Which is my most favorite pasta. I think Asian with that dish—that dish, to me, is about how it appears. It tastes great, but you have a lot of color in it—black and red and green. And the chiles and the mint are that Asian thing, because it has the cooling effect of the mint. And I love it with crab, and then the pop and sweetness of the tomato. It’s fun.

Everybody likes Alfredo, except for me. I’m not a cream sauce person. But that’s how we get to the carbonara, and that dish resulted from me having bad carbonara as a kid. And I realized that that wasn’t what carbonara was, it didn’t have peas in it. So we did carbonara the right way, and that got me to thinking about Alfredo. So how can we have fun? Mushroom Alfredo. It is a light mushroom cream, and then we’re going to bump that flavor up with more mushrooms, give it a little ricotta, make people happy. It’s something new for people, and it appeases my need for not just doing Alfredo but giving it a little twist.

This is not shocking to me, but the number one thing we get comments on is pasta. I love pasta. I want it to be right, and so many people don’t.

Michael Gebert is the pasta-lovin’ editor of Fooditor.

Give someone the gift of good restaurants this holiday season—99 of them, in fact. Get The Fooditor 99 at Amazon and for Kindle here.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.