Editor’s Note: Sadly, not long after this story was posted, Chef Thomas Hauck announced on April 2 that Karl Ratzsch Restaurant was closed.

“MENDOCINO” WAS A BIG HIT for The Sir Douglas Quintet in 1969; less well known is that it was also a big hit for Michael Holm in Germany, and it’s this version, with names like San Fernando dotting its German lyrics like raisins in stollen, that is playing as background music at Karl Ratzsch Restaurant as I wait to have my lunch order taken.

“I love it. My favorite is the German version of ‘Downtown,'” chef-owner Thomas Hauck says of Holm’s cover when he joins me after lunch. “I found this playlist of 50s and 60s pop hits in German, what more could you need? Mix in a little polka and there you go, the playlist takes care of itself.”

The song may be 47 years old, but that’s kid stuff at Karl Ratzsch Restaurant, which dates back to 1904, when original owner Otto Hermann opened Hermann’s Cafe. (At that, it’s still two years younger than another Milwaukee German mainstay, Mader’s.) Otto’s stepdaughter Helen married an employee named Karl Ratzsch, and the restaurant moved to Mason Street and took his name in 1929.

Mama and Papa Ratzsch in front of the fireplace (since burned down), c. 1940s, and Mama and Papa Hauck

This was an age when German food was the height of imported sophistication in dining, in any city with a substantial German immigrant population—which would include both Chicago and Milwaukee. Those places are pretty much gone from Chicago now, but you only have to drive 90 minutes north to find their traditions still alive and serving.

Karl Ratzsch’s (everyone gives it a possessive in conversation) had glory days—hell, glory decades—under Mama and Papa Ratzsch through the 1950s, and then under Karl Ratzsch Jr. and his wife Sally through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Politicians stopped to be photographed here—Kennedy, Nixon, Joe McCarthy. Stars autographed their pictures here—Bob Hope, Paul Newman, Liberace. Geese in the millions were roasted in its kitchen, swimming pools of good German beer and French wine were drunk here, proposals were made and anniversaries were celebrated here, generations of kids grew up behaving themselves at dinner so they’d get to pick a toy from the toy chest on their way out. (Mine did in 2006, when they were 8 and 5, and it was 102.)

The restaurant would stay in the Ratzsch family until 2002, when grandson Josef Ratzsch sold it to its longtime managers. By 2016, they were ready to retire. Hauck, 36, is Culinary Institute of America-trained and a veteran of Michel Richard’s Citronelle in D.C. He’s now known for C. 1880, an acclaimed new American restaurant and cocktail bar in Milwaukee, itself located in a vintage building. He approached the owners about taking it over, and acquired it in early 2016. But as it sat closed for a few months under a young, contemporary chef’s control, many wondered, was the restaurant’s goose cooked at last?

Fear not—Hauck did some modernizing and clearing out, like thinning out the beer steins that Karl Jr. had brought back by the carload from annual trips in the 1970s, but it was recognizably still Karl Ratzsch’s when he reopened last April. More to the point, so was the food—he modernized the approach but stayed firmly in the German idiom. That’s not without risk—even in Milwaukee, it’s not clear that traditional German is a cuisine with a boundless future. But after digging into a plate of wienerschnitzel and a side of the sauerkraut fritters, I spoke with Hauck about his decision to take on a piece of history and keep it going… with his own new touches, like German pop music.

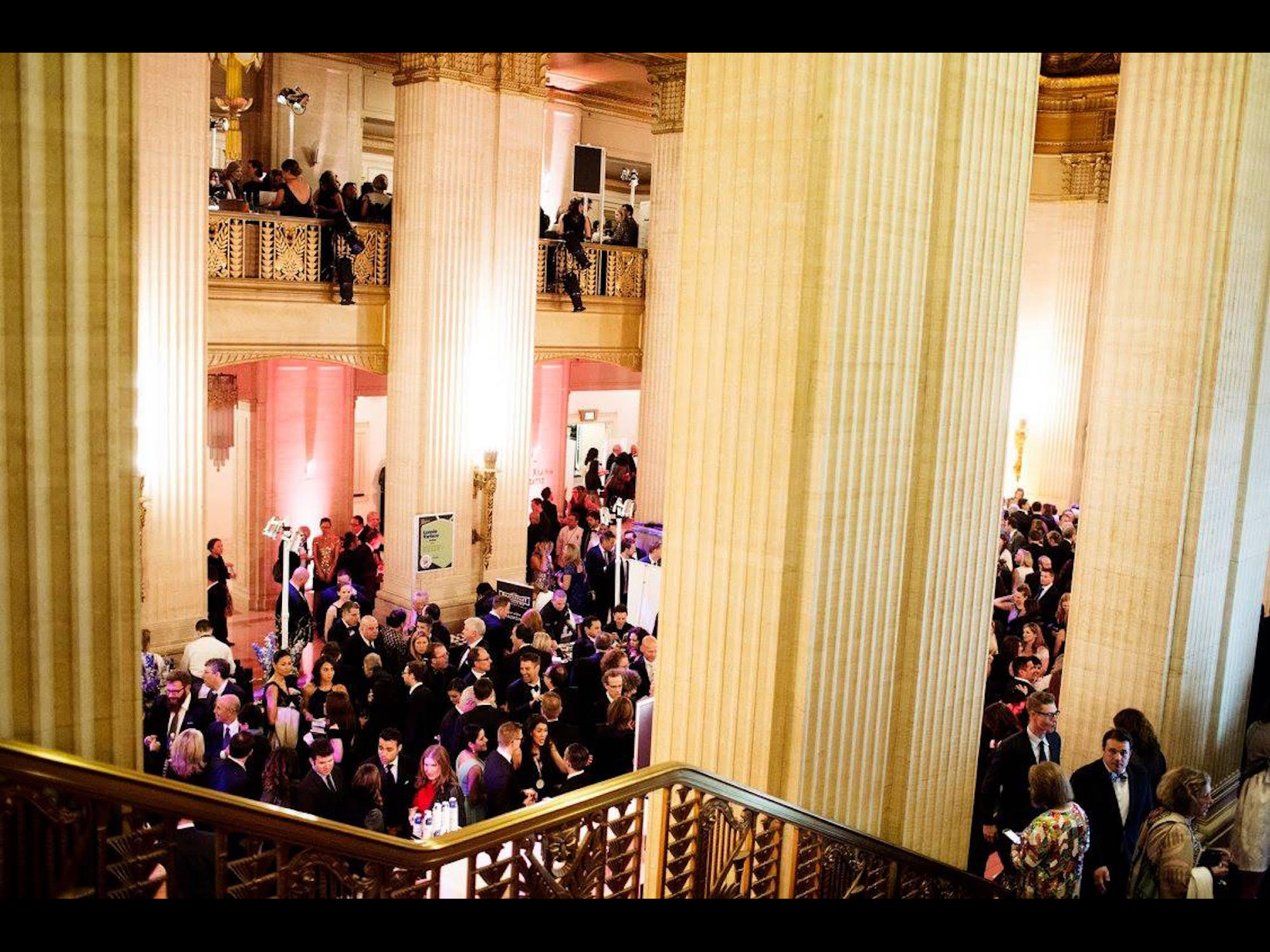

Gallery: A Brief Tour of Karl Ratzsch Restaurant

FOODITOR: Let’s start with your first restaurant… what do you call it casually, Circa?

THOMAS HAUCK: Yeah, C. 1880. People always ask, what does it mean? Well, the building’s from 1880. Used to be a boy’s boarding home, for guys who made fishing nets on Jones Island. Circa, we’re going to be open five years in April, and we got [a semifinalist nomination] for the James Beard awards again this year.

I’d say it’s a chef-driven, modern American restaurant. When you say modern American now, you take your influences from France, or you might find something in Portugal that you really like, or spices from South America or Africa. I think that kind of encompasses what American cuisine is now. We’re a melting pot, and that’s our culture, taking things from different places and making them our own. I definitely think it has a hat tip to the French, because I worked for the French, I lived in France, and there’s a certain element of techniques that, I mean, that’s just the way.

So if your background is so French, what made you want to take on a dinosaur of a German place?

I wanted it to stay around forever. And it’s something I think is important to the people of Milwaukee and the city, its history and identity. I mean, I want my boys to come here when I get older and have a beer—and then go back and wash the dishes [laughs].

I had these memories—I grew up in Port Washington, about half an hour north of the city, and when my parents would have a date night, they would go down to the city, go to Karl Ratzsch’s and then go to the symphony. It held this magical allure of the great place in the city, where you could come here for the holidays and get something out of the toy chest. It’s neat to see it around, and to see people take a new interest in it, that would have thought, oh, I went there with my grandparents, it’s heavy German.

Chef-owner Thomas Hauck

What had it become by the time you bought it?

As you know, the Ratzsch family sold it to the management team that worked for them for a long time. The economy was obviously very different in 2002. They took it and—they had been there for a long time, and for the most part this was the only place that they had worked, so the system that they knew was the Ratzsch system. And you had this real change in what people looked at for high end food, for a date night, for fancy food in Milwaukee or Chicago. So now, Ratzsch’s, it didn’t really fall by the wayside but it wasn’t something you thought about, outside of the holidays.

So things kind of got stuck in a little rut, and then they tried to expand by making lighter fare, or making a broader palate with things like shrimp scampi. Shrimp scampi’s lovely, but there’s nothing German about shrimp scampi. It’s like, how far can you go before you lose what you are? But it’s hard because you want to please the customers.

I think they got to the point where they knew that something needed to happen, but they didn’t really know what to do.

Was the clientele at that point pretty much the old folks?

Yeah. A lot of tourists, because you come to a hotel and it’s like, oh, German food, I gotta go to Ratzsch’s or Mader’s or, used to be, John Ernst, it’s gone now. So there’s a huge convention crowd that would come for a tourism aspect. And then it was older people. And old people and change can be… a slippery slope.

We joke that, 65 and below, we’ve got a fighting chance. Oh, things change, someone else on channel 4 reads me the news now, I get that things can’t stay the same forever. 65 and up it got dicey. They had preconceived notions the moment they walk in the door, why would you do this to my favorite place ever. It was the greatest food in the history of the world, bar none. And I’m like, okay, that’s an opinion…

It’s hard, you want to look at them and say, I didn’t buy this to turn it into this giant money cash cow. I did something because I want it to be around for a long time.

Change is hard, especially for… very senior people. But it is nice, we get some who come in and they might be like, 85, and they had their first date here, sixty years ago. And stuff like that, that’s fantastic. We had an old manager come in who’s 102, he started working here the year my father was born, and he retired the year I was born, and he drove down here and sat and had lunch and told me all these stories. Telling me about Liberace signing the whole guest page in the book, drawing a piano, holding court. It was fantastic and he was tickled pink that it was still here, still around.

Sauerkraut fritters

How have you changed the menu since you took over? Because it didn’t really seem all that different at lunch—it’s a pretty classic German menu.

We took and we stripped away things that you wouldn’t associate with German food. We went back to things that you would actually find in Germany.

If you say “a German restaurant,” usually it’s a Bavarian restaurant. But we broadened it a bit, so the sandwiches we do at lunch, it’s a Saxon sandwich, so it’s a traditional open-faced sandwich. Usually it’s like cheese and jam and kids will eat it, but it could be blood sausage or egg salad. And then we do things that will round it out. Like sauerbraten, you have to have, obviously wienerschnitzel, rahmschnitzel.

Acidity is something your mouth craves—that’s why we love ketchup. And there’s acidity in almost every aspect of German food—the pickles, the sauerkraut, the cheese, everything.

And then littler things, like beer cheese soup, liver dumplings. Make it a little lighter. And we do a potato salad—contrary to popular belief, German potato salad does not contain bacon or mayonnaise. All the time we hear, “Why isn’t there bacon in it?” Well, because that would be an Americanized version.

In terms of modernizing, what does that mean? It’s clearly fresher—

We can find our future by looking at the past. It’s like, if you ever go home and flip through a cookbook from the 70s or 80s, ideas will just come pouring out. It all looks horrible, or definitely dated, but the concept of what they were doing, this totally makes sense.

Wienerschnitzel

We found some old Time-Life books of German food from the 1950s, and—yes. All of this. Everything about this looks great. Maybe the recipes are a little fast and loose with their measurements, but it’s a great groundwork of where to start things.

And then every once in a while we do a different regional menu. Like we’re about to start the Rhineland. A five-course menu from the Rhineland, so we’ll have boar chops on it, we’ll do a potato soup with a savory plum cake, we’ll do freshwater eel in a jelly, and the boar. And then we’ll mix that into the menu, too, just to show that there’s different areas of German food.

But in terms of German food being modernized—when you look at salting and brining and pickling and curing, these are fantastic ways to preserve food. Because of the refrigerator trucks and year-round strawberries, people have gotten away from these things, but we’ve been doing that for generations, and it’s a great way to cook. I think soon every restaurant will adopt, that this is the way, just like farm to table was the big giant catchword ten years ago, and now it’s just the way you should cook.

The acidity is something your mouth craves—that’s why we like ketchup. And there’s a touch of acidity in almost every aspect of German food—the pickles, the sauerkraut, the cheese, anything.

Potato and radish salad

Bavarian food is good, it’s hearty, but it’s like beer dredged in flour and deep fried… it’s like eating a shoe sometimes. Like we have the whole pork shank, because it’s a tradition here, and it’s huge. But people take it down. Surprisingly, it’s big with Asian tourists. They’ll come in, they’ll order it, they’ll take pictures of it, and the server will come back and it’ll be clean. Just the knuckle’s left. That’s impressive. That’s a lot of fat you just ate.

I was a bit surprised that with so many craft brewers in Wisconsin, the tap list is still pretty much German.

Weihenstephaner’s been making beer since 1040. They’ve got it down. They know what they’re doing.

We’re friends with Lakefront Brewing, and we’re friends with MKE Brewery, so we brought them in. But this is a German restaurant, so we want to have old school, classic German beers. We’ve got microbrewers for days at Circa, and pretty much anywhere else around town. But for here, this is like, we want to show you the magic of German beer, Austrian beer.

So even if they’re making that style—

We really like Weihenstephaner, Weihenstephaner really likes us, so that is what we want to do. This is a beer that is so important to Bavaria, and to the German beer culture. They wrote the German beer purity laws—they are the reason. And it’s not something you can get everywhere, at least in Milwaukee. So it’s something that we wanted to showcase and to shout.

Now, if people want to make beer in the style of German lagers, or Bavarian ales, that’s awesome—we always try to rotate things in and out. But we want to show you things that you generally can’t get anywhere else, and that’s the magic of Weihenstephaner Spaten special seasonal ales, or whatever it might be.

Well, we’ve done dinner, we’ve done beer, let’s move on to dessert, something people know German restaurants for.

Yeah, the bee-sting cake, the Black Forest cake, the apple strudel—like, the bee-sting cake is fantastic. There are a couple of stories about where it came from, and the best one is that the Mongolians or somebody were trying to invade this German village, so they just hurled beehives at them from behind the castle. And then when they celebrated, they made yeast cake and covered it with honey and that’s the bee-sting cake.

The Schaum [torte] is huge—that’s kind of more of a Wisconsin thing. It’s like a meringue, marshmallowy, it’s hard on the outside but a little bit softer on the inside. It’s like a jacked-up version of a German vacherin. And then there’s whipped cream and strawberries on the side. It’s like, people from here, their grandmother would have made that for them on Sundays. I didn’t grow up with it, my mom’s from Minnesota, but it’s meringue. People go crazy for it. Especially the older crowd. Liver dumpling soup and schaum, they are ready to go.

So overall, what’s the reaction been to the new Karl Ratzsch’s?

It’s been good. People who care about Milwaukee history have been excited. I think it’s nice that there’s a new generation of people who wouldn’t have thought about the restaurant before—oh, yeah, I went there as a kid, and that’s it. Now there’s something in their mind that, I should at least check this out. Who doesn’t love good German beer, especially in a world where everyone wants to have their microbrew or whatever?

It’s hard because you alienate your old base, or at least 30% of your old base. They can get Facebook-outraged, it’s like watching some kind of hippo get killed in Africa, it’s crazy. I mean, it’s still your friend and we’re still here and you should celebrate that. That it’s not a lamp store now, you know what I mean?

Michael Gebert will write for gemütlichkeit as the editor of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.