NOBODY WRITES ABOUT THE FIFTH CHEF DE CUISINE at a restaurant that’s in its 13th year. There’s always something new opening in Chicago, and that’s where the attention goes. But that kind of new isn’t always all that new. Sometimes for what’s really new, you have to go old, because old is where you find the truly new. No, I’m not high, why do you ask?

I’m just talking about Schwa, the inimitably quirky Bucktown fine dining restaurant that has one Michelin star, and saw two of its cooks (Noah Sandoval and Brian Fisher) go off to have three more between them (two for Oriole, one for Entente). While still being BYO, playing hiphop loud in the dining room, doing shots in the kitchen with guests, and turning out food that’s delicious, imaginative, nerdy, jokey, and one of a kind. Even as it owes an acknowledged debt to Grant Achatz (for whom owner-chef Michael Carlson worked at Trio), and in turn is owed a debt by every restaurant that has broken down the walls between kitchen and dining room, taken the stuffiness out of fine dining, and proved that you can make internationally-acclaimed cuisine in a hole in the wall storefront anywhere in town.

But I wrote all about that for the Reader last year. I’m returning to the subject because I ate there recently and even I, jaded consumer of tasting menus that I have become, was blown away by a dish… or two dishes… really three… that I had. A rollercoaster ride of a dish that kept changing as I ate it.

It begins with foie

It started as a bowl of foie—and I’ve kind of had all the foie I ever need, but this was sharp and on point with tangy citrus notes and deep, oboe-ish chocolate notes. Then I got a spoonful of yeasted ice cream and used it to mop up the last fatty bits of foie, as the rollercoaster slid from hot to cold. Surely now my bowl would be bussed and replaced by something else… but instead I got what looked like a rubber ball with something inside, which went in my bowl and was topped with steaming broth. Now it was a bowl of soup, which continued changing flavor as the ball melted away, releasing a second broth that mixed with the first, and a langoustine trapped inside. (It did not come to life and start growing larger, but that wouldn’t have surprised me.)

I’m a little resistant to trick dishes, but this was a dish with one trick after another up its sleeve, and we were just beaming with smiles at our table as it kept amazing us by becoming something else. Norman Fenton, Schwa’s fifth (he thinks) chef de cuisine, explained how the dish works:

“You’re eating the foie and you’re getting fattiness, and you’re getting acidic notes from the mango and the little bit of vinegar that we use to glaze the trumpet mushrooms, and you get the nuttiness. But what you don’t get is the full-bodied richness. You just get fattiness, and it coats the side of your tongue and the tip of your tongue, but it doesn’t coat your entire mouth. So when you add the yeasted ice cream, everything starts coating your mouth and you’re able to pick up that excess foie fat that helps cut the richness to create a whole mouth experience, and also it takes you from hot to cold, in your mind and your mouth. And then you drop the langoustine ball. The langoustine is set up in the same liquid that we poach the foie in, and there’s a little citrus lace in there as well, and that’s the leaf of the marigold flower.

“It’s tying all the ingredients together as we go down the line. When we brought you the yeast ice cream, that wasn’t tied to anything, but when we brought you the ball, the ball had the royal trumpet mushroom conserva, which there were trumpet mushrooms in the original bowl, and then there’s a mango slice, and you had mango gel in the bowl. And then the langoustine was also cured in the same cure as the foie and is set up in the same liquid as the foie is poached in.”

So the next time you read some Instagrammer raving about some place’s froufrou cheeseburger or crudité plate, recognize that there are people in this city who are engaging with food this deeply and producing food that you can still be thinking about a week later and having “so if Deckard is really a replicant, how do we know his memories aren’t implanted too?” type revelations about late at night. At the risk of giving away the magic tricks, Fenton agreed to show me how it all goes together, in Schwa’s tiny and biliously lit kitchen. But don’t worry if it does; the real magic trick is how Michael Carlson keeps finding and developing talent that keeps Schwa one of the most interesting restaurants in Chicago.

Gallery: The Making of a Schwa Dish (Or Two or Three)

NORMAN FENTON IS FROM DETROIT, and he started his career there at restaurants like a modern French bistro called Bistro 82, rising to chef de cuisine—”We won the two awards that you can get in Detroit, from Hour Magazine and the Detroit Free Press,” he says.

He set his eyes on working at Alinea in Chicago—”I think everybody, when they’re looking at the Chicago market, they’re trying to go to Alinea.” But Alinea was closed at the time for a month-long sojourn in Madrid, so he took a job at The Aviary. “It was different—the pay cut was different, it was definitely different,” he says. “But whatever, I needed to get out. My plan was to work my way up, somewhere, and work for a couple of years, and then go back.”

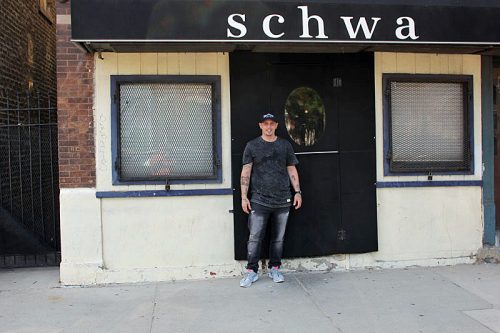

Norman Fenton

But he quickly felt unsatisfied making The Aviary’s food—”You’re not really cooking, you’re assembling. Which I think is true of most kitchens like that—at Schwa, we assemble too, but we’re also cooking all day.” He was ready to move back, and took a job working on an opening in Detroit. But in the meantime he had staged at two places. One, a seafood restaurant, offered him a job three hours into the stage—”But it was very entry level, in my eyes. Tomato sauce was tomatoes, mussels and basil. That’d be like an office job for me.”

“One of the first places I ever ate at here, the first two weeks after I moved here, was Schwa,” he says. “I ate there by myself, they got me pretty drunk, I enjoyed it.” When he was getting ready to move back to Detroit, one of the cooks he worked with at The Aviary had just come from Schwa, and he told Fenton that they were looking for a cook. He applied for the position to then-chef de cuisine Wilson Bauer—”and then I didn’t hear anything from Wilson for a week, and I took the job in Detroit. The next morning, Wilson called me up and offered me the cook position.”

It’s hard sometimes to contemplate changing a great dish because of how many people we serve a night. How many people get to experience this dish?

He worked his way around the kitchen, and when the sous chef left he was promoted to that position. He was also working a lot in the front of house, which was new for him—at Schwa, the cooks deliver plates to the table and interact with the guests, and I get the sense they soon sort themselves into those who want to do more of that, and those who don’t. “Interacting with people and it being so intimate and actually having a personality,” he says, was what appealed to him. “Whoever’s there—you’re allowed to play the music that you want. It really depicts who the people who are working there at that time are.”

I ask him what he knew about Schwa when he first went to it for dinner. “GQ article,” he says, meaning Alan Richman’s 2008 piece about Carlson’s rise, shutting the restaurant down after a dinner for visiting chefs, and rise again. “I’m a pirate,” he says, shrugging a little sheepishly at the fact that he’s identifying with the cliché about Schwa, “so that whole aspect of the conversation grabbed my attention. The fun behind it, the music—I like rap music. There are definitely things about it that are different from most restaurants—that I wouldn’t do.

“But Carlson really gives you a nice outlet to express yourself—to overall, be happy as a human being,” Fenton says. “His generosity, and his kind of father figure mentality. How kind he is, and how humble he is. While working there, that’s what kept me there—and keeps me there.”

WHEN BAUER LEFT, “HE SET ME UP for success,” Fenton says, “but I told Chef [Carlson], I’m going to need you with me.”

Carlson wanted to change Bauer’s menu quickly, to put the stamp of the new collaboration on it. The foie/langoustine duo was intended as a replacement for Bauer’s best-known dish, a play on pork and beans. “It’s hard sometimes to contemplate changing a great dish because of how many people we serve a night. How many people get to experience this dish? You go to Alinea and they have some of the same stuff for a long time, because everyone wants to experience it. But Chef had wanted to change it, he wanted to do a big slab of foie.”

The inspiration for the foie was the flavor profile of Ferrero Rocher pralines—hazelnut and crunchy brioche and the cocoa nib brittle. “That’s one of chef Carlson’s moves, the cocoa nib brittle—I remember seeing it when he did the Manhattan cherry,” Fenton says. “There was a Manhattan glass with a chocolate covered cherry, and the pit was the cocoa nib brittle, and you drank the Manhattan and ate the cherry. So he wanted to do something like that, but incorporate the langoustine.”

Ah, the old Manhattan cherry-crustacean combo, with foie. Fenton says, “That dish was the first thing that Carlson and I worked on, and I was intimidated—I was like, whoa, I just learned how to make the ravioli two months ago! That was a lot of coaching with that one, he would say, I want to do this and do this, and I would just have to put it together.”

“The idea behind it was going from the foie to the soup—those were the two bookends, and it was all based around those two ideas. And over weeks we worked it out. There were a bunch of trials and tribulations with just doing it—we tasked Caleb [Trahan, sous chef] with making the langoustine ball, and it kept coming out where the langoustine would rise to the top. So we had to figure it out, put the langoustine in and set this much, then add the marigold leaf and set this much. We’ve got to refill those balls four times a day. And the temperature in the summer—first hot day, all the balls are melting.”

Filling the balls

I see differences between Bauer’s food and Fenton’s, even as I see they both operated in the established style of Schwa and played with techniques and combinations that Carlson has made use of for years. I ask Fenton how his food differs from Bauer’s and he says, “I think our plating styles are different. I feel there’s a little more masculinity to his food. It wasn’t about doing anything different, it was just about progressing. About making sure that if I replace this beef that Wilson had, that the lamb is going to be better. Not even in my eyes, because it really doesn’t fucking matter what I think, but what the people who dine here think, and what Chef thinks. First and foremost, his approval.”

One thing I noticed—Bauer’s food was notable today for its lack of Asian influence, but there seemed Asian notes to many of Fenton’s dishes, especially a mackerel course which could have come straight from Japan. At first he seems surprised by the notion: “I don’t know where it really comes from, though.”

But he quickly accepts it: “I think it’s because I always end up strolling Joong Boo Market, and Chef does too. And I live by Chinatown, and it was the first neighborhood I explored when I moved. I spent the first three months dining in every place in Chinatown—I’ve got a favorite dim sum place, a favorite duck place, a favorite egg roll. I just find Asian ingredients so interesting, and the culture of food there is just so fucking deep. They’re so adventurous—there’s a lot of things they make that I wouldn’t even try. But it’s easier to create these umami flavors with stuff that’s naturally umami that they’ve already found.”

SCHWA LIKES TO GIVE OFF A NO fucks given attitude, but it becomes clear that if one fuck is preying on Carlson’s and Fenton’s mind, it’s one occasioned, perhaps, by Noah Sandoval’s second Michelin star for Oriole. Which is, if Noah can snag a second one, why can’t they?

“When you dine at the two star Michelins, I think our food is comparable, but the difference lies in the atmosphere, in folding the napkins,” Fenton says. “You look at what they say in the Michelin book and it’s like, ‘If you don’t mind the service being this, the food is this this and this.’ Why can’t the food and service both be the same level? It’s about the entire operation. It can be a difficult place to run—if its not done a certain way. It can get chaotic—you got people in there, BYOB, and sometimes they bring fifths for themselves. But I think Schwa can have all those fun things, and still be this out of the world experience.”

Personally, one of the few things I’ll give Michelin credit for, in their generally hidebound approach to the city, is recognizing Schwa as essential with one star—despite loud music, lack of stemware, and whatever else might have scared them off. I’d hate to see the desire for a higher level of recognition—easily deserved—change what Schwa is, but I also don’t think it’s likely. Being pirates is in their blood, even if the painting of the dining room, which I described in the Reader as “shallow grave,” is now more artful, if still as goth.

Fenton looks at it as “trying to treat the front just as much as we treat the back. It all has to be done organically. You can’t just say you want to go for two stars. if you’re doing it for two stars, that doesn’t mean shit. You’ve got to do it because that’s how you feel. And I think that’s what’s happening with everybody who’s there, they’re really passionate about being there. That’s the key to creating a different atmosphere there, but still keeping it Schwa.

Swirling at the end

“I’ve seen a progression of Schwa since I’ve started there till now, and I feel like it’s trying to just become more refined, but still keeping the character of what Schwa is, who Michael Carlson is. There’s some really odd personalities that make up the place, but the personalities are good, because they’re not as addictive personalities. Like, I don’t really drink. I mean, I’ll do shots with some guests, but I’m not hitting the bottle all through service.”

He says Carlson asked him, “Do you want to be the next chef de cuisine who just gets one star?” Carlson, it seems clear, wants more. “That’s kind of why we’re looking at the dining room, and other aspects that might be appealing to those people that make those decisions.”

Still, Schwa has been Schwa through 13 years and five (he thinks) chefs de cuisine. “I think that’s the goal to keep Schwa relevant, and just push the envelope, you know?” he says. “Showcase the people and the personalities that are there. I feel like Schwa’s still an underground kind of place, but at the same time, it’s still prominent in terms of today’s food in this city.”

EVERYBODY HAS A SCHWA STORY, so here’s one Fenton told me. I asked him how my Reader piece had gone over at the restaurant, and if they had a dart board of my face in the kitchen. He said no, the only target they’ve ever thought about putting up was Kanye West, but they do have ninja throwing stars in the kitchen, which they throw at the wallboard over the HVAC system. The Cubs’ Anthony Rizzo dined at Schwa recently, and then came back and bought out the place for a night. So he and the other players were invited into the kitchen to, among other things, throw ninja stars. And after a bunch of baseball players flinging ninja stars into sheetrock… Carlson had to replace the shredded wall the next day.

Michael Gebert is schweditor of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.