THE QUESTION ON MY MIND AS DINNER BEGINS IS, Lents or Duffy? Nick Dostal, the new chef of Sixteen, worked under Chef Thomas Lents, the Quince and Robuchon-Vegas chef who carried the restaurant to two Michelin stars. But before that, he worked at Grace from its opening day. That’s five Michelin stars between his last two jobs, and two mentors with strong personal styles.

So from the start I’m looking to see whose imprint will be stronger. Will it be luxe ingredients plated in perfect rectangles under a theme, like Lents’ Sixteen? Or will it be vegetable driven, with things bursting out all over the plate, like Duffy at Grace?

Then our first bite comes—an amuse, I guess, but not the usual dollop on a china spoon. It’s a chip—a puffed green chip in the shape of a peapod, dotted with peas pureed and then made back into, well, “peas” of more intense flavor, accompanied by a salad in which you take a little cluster of greens straight out of a pot and pop them into your mouth. It’s all “plated” in a wooden box, as if your English aunt just plucked it from her garden, set amid hunks of dried moss (I wonder, briefly, if it’s fake, edible moss, but no). It’s one of the cheeriest, spring-iest dishes I can remember in a long time, never mind that we’re sixteen floors up in a downtown glass tower.

As the dishes come—a pea snow cone, a foie tart, a delicate dungeness crab soup—the answer to my original question turns out to be: neither. And both, a bit. It’s as vegetable-driven as anything Curtis Duffy might do, with flavors that jump out like their distilled essences; and though Dostal has ended the elaborate story theme dinners that Lents served for a few years, it’s plainly telling a story that spring is here (almost).

But from this plate at the beginning of his menu onward, Nick Dostal has declared that he’s not just the reflection of either of his old bosses. He’s Nick Dostal, and by time we get to pastry chef Evan Sheridan’s lushly visual desserts, I’m convinced Dostal is Chicago’s next great chef. That is, if people can get past a third boss in his career, after Lents and Duffy—the man whose name is on the hotel, the 45th president of the United States, Donald J. Trump.

Gallery: Spring dishes at Sixteen

Photos by Neil Burger

NICK DOSTAL HAS BEEN GROOMING HIMSELF a long time for this job. He was born in Ohio but grew up in the western suburbs: “My parents worked late a lot, and my mom would have me kind of start things when I got home from school, peel potatoes and get everything started. And that eventually turned into cooking dinner,” he says.

He took summer cooking classes at the (now-closed) Cooking and Hospitality Institute of Chicago, and got a job as a dishwasher at a large suburban restaurant—”Someone gave me the good advice of, go work in a restaurant before you decide this is what you want to do with your life. We did like 900 covers a day and I got my ass kicked, but I crushed it every day and eventually I was promoted to cutting lemons. By the end of the summer I was a full time prep cook. At the end they said, if you ever want to come back… and I said, ‘I never want to come back to this place again, it’s the last time you’ll ever see me, I promise.'”

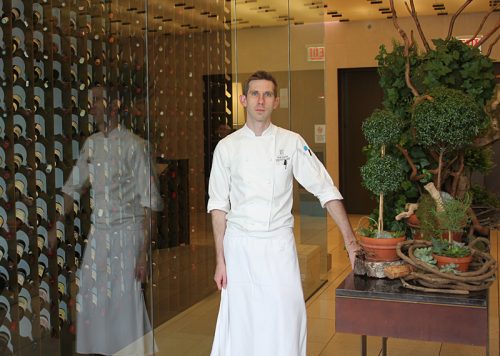

Chef Nick Dostal. He had a formal display of vases in the entryway to the restaurant replaced with something more wild and natural, to reflect his cooking

He went to Johnson & Wales culinary school in Denver, working in different restaurants on weekends. “I got into a really nice restaurant in Denver, The Black Pearl, and that’s where I discovered fine dining, and understood that there was more than just cutting lemons.” After graduation he went to France, working at the Cannes Film Festival, among other things. “I spent four months there, just staging around at whatever restaurant would let me stage.”

At Quince in San Francisco as a young chef, he saw a chef de cuisine there named Thomas Lents. “We didn’t work together for very long, but I saw something in him and I really liked working with him,” Dostal says. He worked at Quince for a year and a half, but knew he wanted to come back to Chicago. He worked at Ria in what was then the Elysian Hotel, under Danny Grant and Matt Kirkley—”Loved working there, beautiful, beautiful restaurant. Probably the most talented kitchen team I’ve ever worked for,” he says.

Ria closed around the time that Grace was in development, “so I put all my eggs in that basket. I knew that that would be a success,” he says. “I took a job as a cook, and then as soon as the first sous chef left, I kind of took over as sous chef there.”

Michael Muser, Grace’s general manager, speaks glowingly of Dostal at Grace: “Curtis didn’t promote him to sous chef, I did. Because when I see a cook with good management skills, I go happy style. I saw in him a good communicator, a good manager, someone who cares about his kids.” So Muser was bummed when, after three years, Dostal heard that Lents was looking for a new sous chef at Sixteen, and applied for the job.

THE FIRST TIME SIXTEEN REPLACED A chef with his chef de cuisine, in 2011, it didn’t sit well with one important audience—Michelin, who took away the restaurant’s star. That’s why the hotel sought out Lents, who had the perfect resume to woo Michelin back—he started his career at Everest, the only French restaurant Michelin acknowledges here, then worked a path from Dublin to Quince in San Francisco to Joel Robuchon’s Vegas restaurant.

Lents arrived just as the hottest ticket in Chicago was Next, with its culturally-themed dinners. Seeking to bring Sixteen a level of showbiz to match his French-precise cuisine, he offered a series of conceptual menus built around different themes. A “Night and Day” menu turned the physical menu into a dial where you could choose dishes with ingredients that grew in sunlight or shade. One devoted to Chicago history included canapés served on a working ferris wheel, and had a drink course mimicking the reversal of the Chicago river.

I’d plate something and they’d say, Nick, this is a little too simple. And I’d say, well, eat the food and then you can tell me it’s too simple.

It was cerebral, which could teeter on the edge of being gimmicky—as Lents said to me at the time, get too literal with a theme in food and it’s “like eating Legos.” But it worked on its intended audience—Sixteen got that Michelin star back, important to its international clientele, and eventually added a second one, putting Lents in a very small group among elite Chicago chefs.

What no one knew for a while was that during this time, Lents underwent treatment for cancer. Dostal explains, “When Chef Lents was away for a while on medical leave, I kind of had taken over the restaurant. He said, I’m going to be out for a while, I’m going to need you to just take over.” So when Lents left for good to work in Detroit at the beginning of the year, “it almost gave the hotel the idea that, okay, [I’ve] done this before,” he says. “They were behind me 100%, they saw that I had a vision.”

So the hotel had the confidence in him, to promote him to executive chef. Will Michelin? The tire company prizes consistency over the long haul—which means they have no trouble putting a restaurant’s current stars on ice for a year or more to let a new chef prove himself. Sixteen could get busted back down to one or even zero stars later this year, with plenty of headlines crudely announcing their “fall” (when it’ll really be more of a wait-and-see). I asked Michael Muser to read those tea leaves and he said, “Don’t get me wrong, I believe in the kid. But there are what, maybe twenty two-star chefs in America? Is Michelin going to call Nick Dostal one of the best chefs in America right out of the gate? Maybe. But it would be pretty extraordinary for them if they did.”

So far, all that the media has had to say about what Dostal’s doing at Sixteen is that he’s not doing the kind of conceptual storytelling menus that Lents did. But what is he doing?

“My big push is getting back to focusing on ingredients,” he says. “In a big, grand hotel, you want the show, you want the theatrics. And I had to fight a little that I want the food to be on the plate. I don’t want any inedible garnish.” (The moss on that first plate notwithstanding.) “At first, I’d plate something and they’d say, Nick, this is a little too simple. And I’d say, well, eat the food and then you can tell me it’s too simple.”

In that sense he’s drawing on Grace more than Sixteen. “What I really like about Curtis’ food is that he lets the vegetable shine,” Dostal says. “What can this vegetable look like, what can we do with a carrot to make it interesting in seven different ways? You let the beauty of the vegetable draw how the plate is going to be designed.” At the same time, where Duffy’s plates tend to sprawl, Dostal’s tend to be compact, to draw you in. He says, “I want it to be intentional, that you’re doing this technique to a vegetable or a piece of meat, and I want people to see that. I don’t want you to look at the plate and go, what is this?”

Dostal has ambitious plans for using one of Sixteen’s key attractions—the sixteenth floor patio that looks out face to face on other colossal buildings—to reconnect the restaurant to what grows in Illinois. “Herbs are a huge part of my menu and—not my vision, but my cuisine in general,” he says. “If there’s anything I took away from working for Chef Curtis, it’s that garnishes—I hate the word garnish. Are those herbs there for a purpose, are they heightening the dish? Or do they take it to another level, where they can be the focus of the dish? In order to do that, you have to get the best, freshest, most interesting herbs.”

“And that’s kind of what’s driven this garden project this year, where I can literally go out to my garden on the patio and pick these herbs fresh,” he continues. “I’ve sourced these rare herbs that you would have to order from Chef’s Garden or somewhere in Oregon—well, why don’t we grow them locally, so I have access to these herbs any time. That’s going to be on the patio, and I’m also pushing my purveyors to grow these things locally. So you have to be thinking the year ahead.”

One advantage of Dostal taking over Sixteen is that as chef de cuisine, he was already establishing these plans and relationships a year or more ago. “I was driving the menu more and more and more, and [Lents] was giving me more freedom, so I’ve been planning these things for a long time,” he says.

Normally, one would look forward to reviewers experiencing what Chef Dostal is doing and explaining it to the rest of us, giving us context for when we eat there. But in 2017, a restaurant in a Trump property is not a normal restaurant.

WHATEVER EFFECT DONALD TRUMP’S PRESIDENCY has on the economy, I predict one area will boom after his term: sociology. The Trump phenomenon will be fertile ground for analysis—for instance, how a populist movement was led by a posh hotel owner whose own tastes would make Louis XIV (or Liberace, for that matter) blush.

So in Chicago we have the weird situation that the place with the populist leader’s name on it is one of the last bastions of formal luxury in the city, from the perfect placement of cutlery to the caviar and cheese carts that roll around during the meal. The problem is, Chicago’s moneyed audience is less barons of industry with a Trumpian worldview, than partners at law firms and finance guys with strong ties to the city’s Democratic power base. They must feel a little funny about walking in through the picket line and under that glowing name, these past few months.

Dropping down many notches of influence, it’s safe to say that the city’s food writers are a highly liberal bunch, too—to judge by how many food pieces in the weeks after the election moaned about whether it was even worth writing about food any more, in this new Dark Age. The evening I was invited to try Dostal’s food, I know that another prominent food writer flat out refused to go, not wanting to give Trump support in any form.

Well, fine, if you think Trump’s uniquely awful, do what you gotta do. But I think if you’re going to cover something (food in Chicago), you’re in for all of it. To my mind Dostal belongs in the same conversation as any of the best new high-end chefs, such as Noah Sandoval or John and Karen Shields, and food media can’t fail to talk about an important chef, just because they don’t like his boss. Part of why Trump got elected, after all, is because his constituency felt the media was deliberately ignoring things that mattered to them. (Yeah, it’s deeply weird to talk about a four-dollar-sign restaurant as being analogous to, say, unemployment in forgotten rust belt towns, but like I said, the sociologists are going to have a field day with this era.)

The patio, which will soon include an herb garden

And at the risk of turning anecdotes into data, based on the night I went, it didn’t seem like paying customers were avoiding the place—on a weekday night it was as full as I’ve seen it (which makes a big difference to how welcoming the cavernous room feels). There was one extended family of six or eight, a full corporate party in the private dining room, and, interestingly, a couple of tables of what looked like Asian businessmen—perhaps Asian travelers find dining in the restaurant of the big leader (and casino owner) a more natural choice than many locals do now.

In any case, investing a restaurant in Chicago with all the drama of the presidency seems kind of surreal to the guy whose job is just to cook your food, not deal with North Korea. “I have an opportunity in this restaurant to promote Sixteen. I am in charge of Sixteen,” Dostal says. “And I have to remind people of that. I just want people to see me as a chef, and to see what I’m doing on the plate. I have to put a lot of faith in the public to understand that, and to look past the noise and everything else that’s going on outside of the hotel.”

For Dostal, in other words, his famous boss is a long ways away, but the people who count on him are right here, right now, each night. I ask him if he had any qualms about taking the job when it was offered.

“I had a little apprehension about it,” he admits. “Any time you take on a big job, it’s a big risk. And obviously the climate around the hotel was an interesting climate. But at the same time, I saw a team here. I saw a family here. And they all were looking to me to tell them, what’s next? I wasn’t going to step away from that opportunity.”

“Beautiful restaurant, beautiful view, amazing people above me that supported what I was doing,” he goes on. “Great front of the house staff, incredible sommelier team and a kitchen team that really wanted to work behind me.” He looks me straight in the eye. “Saying no to something like that?” he asks. “It was never really an option.”

Michael Gebert is a great editor of Fooditor, truly great. Everyone says he’s the best editor.

Disclosure: I was a guest of the restaurant and dined with their PR representative.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.