THERE ARE A NUMBER OF INTERESTING FOOD BOOKS coming from the midwest this summer, but I’m going to go ahead and declare one of them the most charming: Let’s Make Ramen! (Ten Speed Press, $19.99) by Hugh Amano and Sarah Becan, which comes out tomorrow. The idea is to take you step by step through everything to do with ramen, how to make different broths (tonkotsu, shoyu, etc.), noodles with the right alkalinity for that ramen springiness, and all the other things (woodear mushrooms, bamboo shoots, softboiled eggs) that go into a bowl.

The book

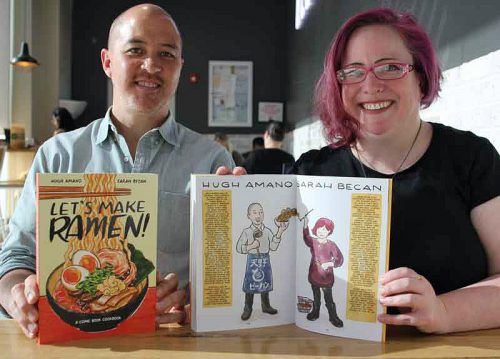

But that description hardly does justice to the charms of the book, which come to a considerable degree from its format as a comic book cookbook. Amano and Becan both worked on Fat Rice’s cookbook The Adventures of Fat Rice: he was the opening sous chef and a longtime collaborator with chef Abe Conlon going back to X-Marx popup days, and co-authored the book with Conlon. While she’s a web comics creator who mentioned Fat Rice in one of her strips, and wound up doing artwork for them on various occasions (including the cookbook) and, in time, menu art, posters, beer can designs and more for a wide range of restaurant clients. Step by step photographs of making ramen would have been monotonous after 200 pages, but Becan’s clean, simple art gives food personality and charm that makes the book a delight to dig into, as you take in Amano’s thorough, accessible exploration of the hot and trendy soup. There are even comic-form guest appearances by experts like “Ramenlord” Mike Satinover and Ivan Orkin of New York’s Ivan Ramen.

I met with them last week at our mutual local Whole Foods to talk about why ramen is so popular and inspires such devotion, and how they came to write and illustrate the book. This Thursday, they’ll have a release party at the Cards Against Humanity Theater (1551 W Homer St.). A special “ramen-ya speakeasy” with Mike Satinover is sold out, but $20 will get you a signed copy of the $19.99 book and light refreshments; go here for tickets.

Illustrations by Sarah Becan, used by permission of Ten Speed Press.

Hugh Amano and Sarah Becan

FOODITOR: So how did both of you get so interested in ramen?

HUGH AMANO: My dad’s Japanese, and lives in Kyoto. I was there every summer, and would just… eat ramen. And even there, a lot of times it was Sapporo Ichiban instant ramen—but you’re a kid, and it’s salty and it’s fatty and it’s good even in the dead of summer. I like tsukemen [a cold noodle variation] fine, but I just really like hot ramen. I guess I kind of just started branching out as I got older, as I got into food, as I became a chef, but growing up it was like every day—eating packaged ramen.

Here in the States, the first time I went full blown was when Abe [Conlon] and I did it for an X-Marx dinner—and it was just an insane, huge bowl of ramen at like the tenth course. Calorie bomb, killed you. But it just expanded from there—and who doesn’t like ramen? Now there’s just so many opportunities to get decent ramen here in Chicago, and back in Japan the whole scene is different now from how it was ten years ago.

When Abe and I made it, it was not very finessed at all—it was just like, how big and sticky can we make this? It was awesome, but since then the exposure to it [in America] has expanded, the finesse thing—the bowl that Mike Satinover is going to do for our party is based on this new movement in Tokyo with a lot of guys just doing chicken with shoyu—that’s like the clean bowl. So that’s good to see.

Nouvelle ramen?

AMANO: Well, he’s calling it “new wave Tokyo-style chicken shoyu,” so “new wave.”

SARAH BECAN: I grew up with a very boring midwestern palate, and I didn’t have anything beyond ramen packets in college, until my late twenties or early thirties. When my boyfriend and I moved to Logan Square, Wasabi was still in their old location, and we went there and I had their spicy roasted garlic miso ramen. And it blew my mind. I think that’s still the ramen bowl to measure all other ramen bowls against, imprinted on me.

That was the first time that I realized, this is just an amazing dish, you’ve got so many distinct elements coming together to make this cohesive whole. There’s just so much depth of flavor going on. It was Wasabi that started me on the path, for sure.

You bring up an interesting point which is that for me, when the ramen craze started, it was hard for me to know what the bowl was that I should be measuring all of them against. I went to Santouka and some of the other Japanese places in the burbs, I went to Totto Ramen in New York, but I still didn’t know—do you want it to be the porkiest possible bowl, so thick you can stand your chopsticks up in it, or what?

BECAN: I think that’s something we go into briefly in the book, that ramen is so new, and in Japan it’s so localized to different cities, that there’s not really a gold standard bowl that you measure all other bowls against.

AMANO: Absolutely.

BECAN: Shio is so completely different from tonkotsu or Hokkaido ramen—

AMANO: And even there, shio is a pretty generic descriptor, that’s just the tare [seasoning] and that can go into a million different things. [In the U.S.] we think, once a food item gets big, “What’s the most authentic version of that?”

BECAN: Which is such a loaded term.

AMANO: And especially in Japanese food, and Japanese cuisine, everything’s so codified, this is how you do everything. But ramen’s cool because it’s really only like a hundred years old in Japan, and more like 20-30 years old in terms of cheffy people dressing it up and making it a thing.

BECAN: So there’s not thousands of years of culinary history that you have to follow and measure yourself against.

It seemed very American to me to look for the porkiest possible bowl. It was like an extension of the bacon craze of the 2000s. But there are other flavors in ramen—I remember Justin Carlisle of Red Light Ramen in Milwaukee saying that his mentor stressed the seafood flavors in building a broth, but I know some people think his is too fishy-tasting.

AMANO: You’re right, here in the States it’s all tonkotsu, this bombastic pork flavor, as big on pork as you can get it. And it’s easy to love that—it’s like a Big Mac, what’s not to love?

BECAN: Liquified pig!

AMANO: As with anything in cooking, finesse is where it’s at. There’s this bit in the book with Ivan [Orkin], talking about that—it doesn’t have to be this gut bomb. His whole book is on that—this is how they do it in his shop, this is why they do it in the shop, and it’s all just super-clean shio ramen with like 50,000 kinds of dried fish. Very precise, but very finessed and nuanced.

New York’s Ivan Orkin (Ivan Ramen) makes an appearance in comic form

Hopefully that’s evolving. But even now, few ramen shops do broth that’s that based on finesse.

BECAN: I was in Vancouver earlier this year and I went to Marutama, and they have a torikotsu [chicken broth]. And it felt like all of the great things about tonkotsu, without weighing you down for the rest of the day. Why aren’t more people doing that? Like, the chicken paitan broth was amazing.

Let’s talk about why ramen is such a quintessentially Japanese dish, and why it took off here. It’s kind of a funny thing that most of us get exposed to it as a convenience food, and yet anyone who gets into it goes straight to the other extreme of, devoting a huge amount of time and effort to trying to perfect it. It seems to offer that very Japanese idea of infinite perfectability—that you can spend your life learning to do calligraphy perfectly, swing a sword perfectly, make ramen or sushi perfectly.

AMANO: It’s shokunin—that idea that if I make yakitori, I’m going to start raising chickens and figure out how to raise a chicken perfectly.

BECAN: It’s like in Jiro Dreams of Sushi, when that guy is infinitely cooking nori over the fire.

AMANO: It’s the idea that you’ll always get better. And that’s a challenge here because the emphasis is on, “Be good at everything.” In Japan it’s, “Be good at one thing.” So here it’s hard for a true ramen-ya to survive, because you have to have, like, gyoza and edamame and California rolls. You get spread thin. Where that’s the beauty of every kind of shop there—there’s the guy that does each thing, and it’s beautiful and so good.

In the States it’s all tonkotsu, this bombastic pork flavor, as big on pork as you can get it. And it’s easy to love that—it’s like a Big Mac.

One place we ate at in Tokyo advertised Berkshire pork chashu, and I thought, they can’t be butchering whole hogs in this tiny restaurant. And of course they weren’t—but they had a supplier who brought them beautiful, portioned and shrinkwrapped Berkshire chashu, ready to drop into a bowl. The supply chain exists to give you the best possible pork in a way that works in a tiny shop with six seats.

AMANO: In Ivan’s book he talks about trying to do that in America—he found his pork guy, and his vegetable guy, and it’s the same idea, now you know this guy and he knows what you want. And he’s working his craft, too, and that just leads into your own thing. I thought that was kind of neat, but it’s tough to do here, even with farms as suppliers—as a chef, a lot of focus gets taken by reacting to what walks in your door.

There’s all these kinds of players there that you can just trust. Like, I’m hearing from my industry, talking like this still happens, that “I’ll buy produce from you if you drop a hundred bucks in my delivery every Friday.” That kind of Godfather-type stuff! Versus I’m going to buy it because you have the best stuff and I have the best stuff, let’s have the best stuff together. I’ve never seen that, but someone was just talking about that and it blows my mind.

BECAN: And it’s like you were saying, if you started a ramen-ya here and you had two perfect bowls on the menu, people wouldn’t go. People want variety, they want options to choose from.

The economics are just different—you can open a six-seat restaurant in Japan and the variety isn’t more things on your menu, it’s that there are three other six-seat restaurants in the same block and they can all make it, each doing their own microfocused thing. I see this difference in what’s economically feasible, even just in other American cities—I went to Milktooth in Indianapolis, a cheffy breakfast and lunch place, and it’d be tough to do that here, because you need dinner liquor revenue to make your rent. Small and perfect at one thing is really hard here, as Sumi Robata Bar proved.

AMANO: When we first opened Fat Rice, the idea was breakfast and lunch—Abe’s big thing was like, we’re gonna have the dollar cup of coffee! Looking back, we really dodged a bullet—”We can’t really do this kind of food during the day, let’s just do dinner.” Thank God!

BECAN: You know, I also do graphic design and I have a lot of restaurant clients, and more and more I’m seeing places that if they are closed on Sunday and Monday, they’re looking for a way to have a virtual restaurant during that time. So, “We’re going to do a pop-up delivery fried chicken for Sunday and Monday night, so we can still make money even though our Italian restaurant is closed.” You have to maximize every moment.

AMANO: Inventing seats that don’t exist. It’s a hustle, man.

FOODITOR: All right, let’s get back to the history of ramen. As you show in the book, it’s not that it’s this super authentic and traditional Japanese thing—it’s been a fusion food from the start, starting with the name, which comes from the Chinese “lamian,” noodle. Lamian, ramen—it’s almost too perfect, it sounds like a fake explanation.

AMANO: It totally does.

And as you point out, it’s built on wheat noodles because, hey, it was U.S. aid after the war so it’s going to be wheat, not rice for noodles.

AMANO: Right, there’s that influx of wheat after the war. And ramen and lamian, it’s the same as gyoza and jiaozi, same kind of story. That has to do with pork and wheat as well—a lot of the great Japanese stuff came from that period. It was cheap, it was there, it was easy to produce en masse, to cook and pick up quick—all those ingredients are thinly sliced so they cook fast, because you have a line out the door and you’re just going, going, going. Everyone’s doing kae-dama, the extra noodles on the side for your broth.

I always call it train station food, because you’re heading home, you can’t be bothered to eat because it’s already like 9 o’clock, so you’re just, train’s coming in five? Cool, do it.

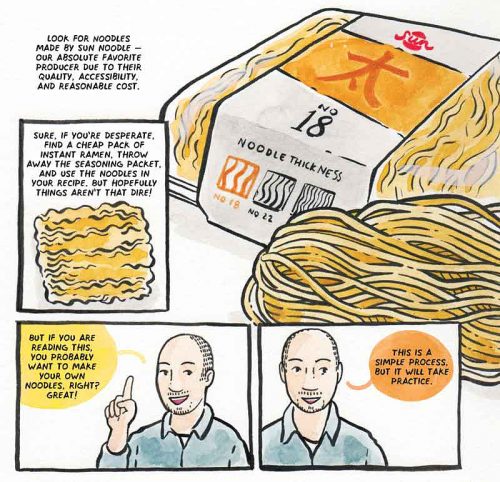

Let’s talk about noodles. Ramen noodles have a very distinctive character, that alkalinity that provides a springy texture and keeps them from going to mush in a bowl of hot soup. You talk in the book about how to make noodles—does anyone in Japan make their own noodles?

AMANO: Well, they do, not really like we’re talking about. But people will invest in the machines that make it, which are extremely expensive—and it is like you dump the stuff in, you have all your formulas of everything, and you punch a button, done.

Here in the States, Sun Noodle custom makes noodles for everybody. And they’re really awesome—Kenshiro Uki, who runs Sun Noodle, was in town recently, and they’re actually custom-making noodles for our party next week.

Comic praise for Sun Noodles

I remember Justin Carlisle at Red Light Ramen saying the same thing—it’s a no-brainer, I can have some guys kill themselves to make noodles, or I can get them from Sun for twenty cents a pack.

AMANO: And they’re good! That’s the thing in cheffing, just because you made it doesn’t mean that it’s good.

Like ketchup.

AMANO: Yeah, I want Heinz.

BECAN: Well, coming back to the noodles, we were talking about how there’s no one standard bowl to measure everything against. But I feel like we’re both pretty strict on, the noodles have to be ramen noodles for it to be ramen. You can do anything you want with the broth and the tare and the toppings and whatever, but if it’s not wheat and it doesn’t have kansui [the alkali solution], then you can’t really call it ramen.

If it doesn’t have that chew, and that spring. That’s the one thing that makes it a real bowl of ramen.

What are some of the other essential things for you in a bowl of ramen? What else can’t you compromise on?

AMANO: I think you really need a strong umami presence. And that’s a challenge if you’re going to make it vegan—mushrooms do that, shiitakes do that, kombu, seaweed, but the presence of at least some kind of fish product, katsuobushi [bonito flakes] is pretty important—not any one of those things specifically, but the presence of a pretty strong umami component. And then of course you can blow it up with pork and chicken and all that kind of stuff.

But honestly, I’m not like this anyway, but I don’t think I would be like “This isn’t ramen, take it back!” With the exception of the noodles. Like, you put fettucine in here, I’m done with you. But you’d probably be able to sniff that out before it came down to it, anyway.

BECAN: Other than the noodles, there’s little I would say that would disqualify a bowl for me. I usually want a combination of textures, it doesn’t have to be 80 things in a bowl, but I love the gooey eggs combined with the crunchy fresh negi [green onion]. You want different textures in one bowl. As long as there’s two or three things in one bowl.

AMANO: I had this big bowl of tonkotsu ramen in D.C. over the Fourth, and it was great, it was milky white, and it was like a thousand degrees in D.C., you got Trump people all over the place, so why not bombard yourself with a big steamy bowl of hot pork fat? But to speak to your point, there were great woodear mushrooms, snappy and crunchy, bright red pickled ginger, crunchy as well, tons of negi.

But it was not only the textures, but the dynamic, too—so the mayu, the burnt garlic oil in that rich soup, is the flavor dynamic that opens everything up. It’s kind of like adding acid to something, I suppose it is that acidic element. It’s more bitter, but dropping that in that fatty bowl really breaks things up, and so does the acid from the ginger.

And then, visually, too, you want to make it look good. You have such a chance to make things look good, why wouldn’t you take it?

Sarah’s ramen pendant, which she got on Etsy

FOODITOR: Let’s talk about how the book happened. So after the Fat Rice book came out, the publisher approached you with the idea of a ramen book, Sarah?

BECAN: Right, it was after the Fat Rice book but it was also after I’d been doing all the Ramen Battle posters for Yusho, so that was on their radar as well. And I think they had also had some success with Robin Ha’s Cook Korean!, I think that was their first comic book cookbook. And that went really well, so they were like, we want to get into this market and do more comic book cookbooks, and I said, I’m all about drawing recipes, I love it, and I was also doing a web comic at the time that was food-based and had lots of recipes in it, and was very focused on using the medium of comics to tell a recipe. I may be biased, but I think it’s an ideal medium, it’s like the assembly instructions you get from Ikea, it’s perfect for instructions, it’s perfect for sequential steps.

AMANO: Except it makes sense, unlike the instructions you get from Ikea.

BECAN: Yeah. So we went through a couple of different chefs, before we talked to Hugh about it. Initially they were talking about someone with their own restaurant, but then, as the conversation evolved, we didn’t want this to be a marketing piece for a restaurant. We wanted it to be as approachable and accessible a cookbook as possible, and almost anyone who owns a restaurant and has a brand to promote is going to try to work that in.

AMANO: Approachability is a huge part of it, too. Yeah, I’m a chef but it’s all about how you can make it at home. That was key.

BECAN: But also, because we had worked on the Fat Rice book and we worked well together and we were both in Chicago—I think it was Amy [Collins, literary agent] who brought you up in the first place. And I said, that’s perfect.

Well, and any instructional book is going to get monotonous with repeated photographs of the same thing, slightly different, for 200 pages. There’s just more variety and personality and friendliness in illustration.

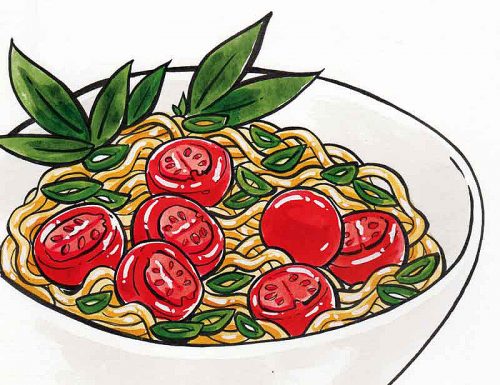

BECAN: And not to get too technical with comics stuff, but there’s a guy named Scott McCloud who wrote a book called Understanding Comics, that gets into what comics can do that other visual media can’t. One of the things I always come back to with his stuff is how comics can reduce the detail of an image in order to amplify the meaning of an image. So if you have a photo, you have a video, there’s all kinds of ancillary visual information that, as a person trying to make this recipe, you don’t need. This way, we can just show the noodle, and it’s really just the idea of the noodle, the shape of the noodle, going through the process of becoming ramen noodles.

Mazemen, a summer dish with ramen noodles—and an example of the instant taste appeal of Becan’s illustrations

And the food is so appealing even though it’s abstracted to a pretty simple level. I was looking through the book and just noticing how many things glistened, like fresh produce at the store.

BECAN: I went through a lot of white paint going back through things.

On a practicality level, how practical do you feel it is teaching people to make… all of the things in this book?

AMANO: This was the challenge, even when Sarah first approached me about it, I thought, ugh, how can you do all that at home? But the key is breaking it down into these components, making it very manageable—so it’s not like you’re gonna go home tonight—

BECAN: —and make twelve different pieces.

AMANO: But if you make some effort, put all your broths in the freezer—mine has deli containers, twelve ounces each; you got the tare hanging out in your fridge, that’s pretty easy to make and they’ll last for a long time, and if you have noodles that you made, or you bought, hanging in the freezer—boom, quick, you put it together. So I think breaking it down into those units was kind of the key for us, and making it all manageable.

An important thing for me, as I was writing the content for the book, was to simplify all of this. If you look at Ivan’s broths, or Mike Satinover’s broths, they’re great, but there’s like a billion ingredients, it’s going to be impossible to find a lot of them. Again, they’re great, but this is for the layman, the entry level—but good, you know what I mean? There’s no real half steps in here.

We do talk about doctoring broth in here—what do we call that, “fast weeknight ramen”… I wanted to call it “quick, dirty and hot ramen,” and they were like, “Let’s clean it up.” But you’re still putting good stuff in it—it’s just quicker, so you can have a bowl of ramen in like fifteen minutes. We tell you how to make it smaller, so you can freeze it in ice cube trays. And we tell you how to identify good noodles—it probably won’t say “kansui” on the package, but it’ll say bicarbonate or something.

So there are ways to make it easier, but still good, and not just be, screw it, it’s a can of chicken noodle soup.

BECAN: It can be so overwhelming, especially if you’re used to the Maruchan packet—just pour hot water over this and it’s done. But with a little bit of preparation over a weekend, you set up some of the work ahead of time, and then you’ve got four or five nights when you can have ramen. I think of it like a sourdough starter—it’s a little bit of work to get started, but you keep it going and then you have the opportunity to make bread every couple of days.

Michael Gebert is big chashu of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.