BILLY DEC IS EXPLAINING THAT BEING A PAL to celebrities is no big deal—not something he tried to make happen, just the natural way of things. “I just meet people in our venues so much, and I’ve been doing it for so long, that if I get a call from a friend,” looking to ensure a celebrity has a good time in town, “they end up putting them with me, and the next thing you know I’m just taking care of people. The celebrities are just one of a hundred people I take care of, and most of them are just regular people,” he says.

It just happens, see? Well, if you get a reputation for handling the presence of celebrities smoothly, in a sense it does tend to just happen after a while. Which is maybe why it makes sense that Dec’s empire is expanding to a new center of the entertainment industry—Nashville. Except for one thing.

“The problem is, I don’t know country music, so I don’t know anyone!” he laughs. “And Nashville’s the kind of town, kind of like Chicago was 15 years ago, where they don’t make a spectacle, they don’t take pictures. They won’t talk about it, so no one even tells me. If that’s so and so, they won’t tell me.”

But in the charmed life of Billy Dec, it doesn’t seem to hold him back. “I’m clueless and they love it,” he says. “It’s the most laid-back natural place, and it’s really artistic, it’s about the art, it’s so cool. They do these songwriting nights they invite me to, where they just sit around and play.”

This despite the fact that, as the longtime owner of many hot Chicago nightspots, Dec initially could not have cared less about country music. “I used to hate country,” he admits. “I have this old beatup Bronco, it’s like missing a top, all-American old. And I was driving it down the hills of Nashville, the rolling green, and I don’t have anything fancy in it, just an old radio, and I turn on the radio and I get country, and it wasn’t like pop country, it was old country. And I got it. I felt it. Now that I’m in my truck, I can feel the air, the sun’s hitting me and no one’s around—I get it.”

Billy Dec’s next act: Thank God I’m a Country Boy? Perhaps, but the question is, which country?

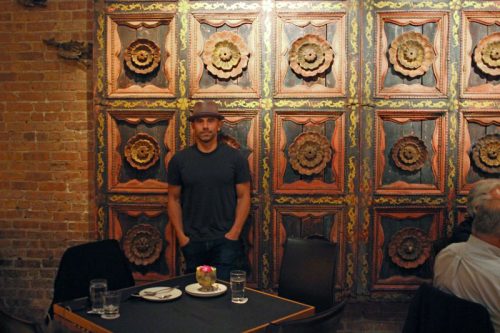

Billy Dec in front of an antique Tibetan ceiling, at Sunda

BILLY DEC KNOWS EVERYONE AND EVERYONE knows Billy Dec, at least if they follow the food and beverage scene in Chicago. The onetime owner of Rockit Burger Bar and Underground and Sunda and Le Passage and on and on, fit and fedora’d and visible in society columns, seen on TV food segments and as a bit player on TV shows like his pal David Schwimmer’s Friends and Empire, appointee to commissions on Asian-American affairs and bullying in schools by President Obama. For 20 years, if there was a party in Chicago, it seemed like Dec was in the middle of it, the living, high energy embodiment of good times, bro!

Once I was at a James Beard event in Chicago and my seat wound up getting taken somehow, so Kevin Hickey, who was then involved with Dec at Bottlefork, waved me over to Rockit’s table. Dec was on the other side, holding court and being the party as usual. But at some point I found myself face to face with him—and he immediately peppered me with smart questions about Fooditor’s strategy and positioning. (Smarter than I could probably answer after an evening of flowing champagne, anyway.)

I’m not saying that Billy Dec, Party Guy is an act, exactly—no one runs clubs for two decades, or gets on TV regularly, who doesn’t enjoy it or the spotlight. But the idea that Dec is just a lucky bro who went straight from the frat house to king of the nightlife scene is quickly dispelled by the actual history of his allegedly charmed life, marked by struggle and drive. His mother was an air hostess from the Philippines, his father was a top real estate developer—as he says to me at one point, “My mom looked like a cute, spunky short brown island girl, and my dad looked like you. German-Polish-Czech-Italian mix.”

Then his dad’s bipolar condition, shared by a brother, led to the family losing nearly everything. (Both are dead now.) As Dec has noted in past interviews, he observed that the attorneys were the only ones in his family’s spiraling disaster who seemed to know what was going on. He went to University of Illinois for law school, and found his real career in clubs and restaurants along the way.

I always wanted to do a Filipino restaurant, because I wanted people to love it. I know when I went away to college, I missed the flavors really deeply—like something was wrong with me.

“In high school my dad got really sick, and my brother got sick, and so it was really just a way to make money,” he says. “I was working a lot of restaurant jobs, and then when the restaurant closed, I got a job at a nightclub. I worked the door, and then I became a promoter, and it was the only thing I knew to make money for law school. And then there was an opportunity to take over a pizza place, and I turned it into a nightclub on the other side of Cabrini. I’d try to study in the back, and then I would do laps [around the restaurant] and act like I was partying and out of my mind. And I’d close it down at two, and be in class by eight.”

Even his iconic look came out of desperation. “‘Oh, your look is jeans, T-shirts, tennis shoes and a baseball hat.’ I was working around the clock, it was all I could get by with,” he says.

So, it just happened. But looking back, he was getting a street-level education others were paying for. “The guys who were smarter than me, they seemed to be in better classes, they all seemed to be in advertising. Or accounting. Those were the two to go into. They knew so much, they were talking about these companies, they were interning for them. And I had to work. I was driving back to Chicago every weekend. It was a catch-up game. And I was promoting parties, and coming up with crazy marketing tactics to create really interesting experiences with food and drink. And bringing artists together to create weird experiences.

“Some of those advertising guys, those accounting guys, they come in here and they’re like, ‘Oh, you made the right decision.’ Especially the lawyers, man,” he says, the law school graduate who never practiced law. “I get the, ‘Oh my God, you’re so lucky, I love having parties at my house, I should totally do a restaurant.’ Please don’t. I mean, I’ll give you the keys, we’ll just pretend, so you can get it out of your system.”

Sushi at Sunda

WE’RE HAVING DINNER AT SUNDA, Dec’s Asian restaurant in River North and one of the main properties he has left after he and his partners broke up Rockit a year ago. At the time everyone assumed there had to be some juicy story behind it, but he shakes his head. “Burger Bar we had a 10 year lease, do you want another 10 year lease? No, bucket list crossed off, done,” he says. “I had awesome partners, super amicable. Some [properties] I sold my shares, some, you take this one and I’ll take that one. Because I was giving 110% of my time to all these things, and what I wanted to do was give half my time, 75% of my time, to the thing I loved, and then find more things that I loved and had never been able to give time.”

The one he loved and kept was Sunda. Sunda debuted in 2009, not long after the 2008 housing crash, as a glitzy River North take on pan-Asian food, the opening menu by itinerant chef Rodelio Aglibot, a specialist in Asian concepts. Heather Shouse in Time Out Chicago summed it up at the time as “the one opening in recent memory that’s so excessive in scope, stature and style that it might as well tack on the tag line ‘Recession be damned.’”

“The best time to open is 2009, 20 below in February,” Dec observes caustically. “Especially in River North, when you know there wasn’t much here. We built this and people said, oh, they’re gonna get crushed.”

Few noticed at the time, but for Dec, Sunda was his attempt to reconnect with the Filipino roots he’d kept on the back burner while running clubs and burger bars. “We called it New Asian because ‘Asian fusion’ felt like people taking one thing and another and just melding them,” he says. “And I was like, no, I was in Hong Kong and I had this dish that I loved. My goal was to elevate the ingredients and the cooking techniques and the presentation—so it had a higher probability of being celebrated by Chicagoans who at the time had a lot of exposure to high level food. You know, in 2009 there wasn’t a ton of people calling themselves foodies and taking pictures of their food and stuff.

“I always wanted to do a Filipino restaurant, because I wanted people to love it. I know when I went away to college, I missed the flavors really deeply—like something was wrong with me,” he says. “I wanted to open a Filipino restaurant but I saw people go too mom and pop or too high end, and I couldn’t figure out the balance. What I felt was that every time we went in the Philippines, we would stop—Tokyo, South Korea, Beijing, popping around other countries. Then I started backpacking a lot, especially as the Philippines kept evolving so much and it had so many other influences, that as I looked at my pictures, it was always other countries, too. It’s funny when people talk about ‘authentic’ Filipino food—because they were always taking stuff from China, from America, fried eggs, bao buns. Always evolving and grabbing different parts.”

With that experience shaping his thinking, incorporating Filipino dishes with other, more familiar dishes from Japan (sushi) or China (soup dumplings) or Thailand (Thai fried chicken) was a way to slip his heritage in alongside things already within diners’ comfort zones.

“I basically built the culture [of the restaurant] around my Lola,” he says, using the Filipino word for “grandma.” “She would bring you in and embrace you and make you feel like a million bucks, and feed feed feed you. In 2009, people got their ass kicked so bad, that they appreciated that. And the strategy that we picked allowed people to sit at a table, feel really great, be in a really beautiful place in 2009, and kind of navigate their own journey through southeast Asia, such that they didn’t have to spend a ton trying Filipino food, or Vietnamese, or Thai.”

Ordering

“WHEN MARCOS WAS IN POWER, THERE WERE RUMORS that he was going implement martial law, which he eventually did [in 1972]. So my mom took her mom and got out,” Dec explains.

“My Lola took care of us, and she happened to be this amazing cook, everyone knew it.” But kids don’t look at getting fed as a culinary experience—”That’s just Lola. It’s only now that I reflect on it and yeah, there were strangers who’d come over to pick up bags of food. Somehow they always knew when she was making shopao. She’d make trays for people for birthday parties. Before we’d go to school, I would see all the vegetables laid out, and she would cut them very finely, and make all the insides of the lumpia, and by the time we got home, she would let us fry them.”

Like so many kids with an immigrant parent, Dec had conflicted feelings about his family’s food. “At some point, you try to fit in, and you start to push away. ‘Mom, why can’t we have pizza bagels and Pop Tarts?’ You have a sleepover and you’re so embarrassed because you ordered in pizza, but there’s rice. And you’re like, mom, dad, Lola, what are you doing? People are like, what’s that smell?”

Dec had that feeling in mind when he agreed to be appointed by Obama to a presidential Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and another on bullying, which he says disproportionately affects Asian-American kids. “A lot of kids these days, especially in the Filipino-American community, have completely detached themselves” from their heritage, he says. “I think it’s a shame, but I understand, there’s not a lot of positive content out there, there’s not a lot of positive role models. No one’s making the food and the culture look extremely adventurous and sexy and fun.”

Dec says he was aware of feeling separate early on. “You end up not looking like any of your cousins at all, and you’re always trying to search for your identity and connections.” Once he was in a position to, he began exploring his Asian heritage. “In the past few years, I’ve gone back every year, and before that, every two years. But they were such short trips, and I wanted to go to Japan, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines part got shorter and shorter. Never a time to really explore too much of anything.”

Then, a few years ago, his Lola died, as did another older relative within a short time. “My Lola passed away, and none of the recipes were written down, and basically I thought, what assholes we are,” he says. “You want to fit in so bad, that you’re not embracing it.

“I just think it’s a common problem, and at a time where you hear so much politically and in media about alienating people based on culture and color and whatnot. And I wanted to do something that looked cool and adventurous. But meaningful—and of course food-heavy.”

Sous chef Louie Yu, with lechon

BEFORE WE MET FOR DINNER, DEC SENT ME the latest trailer for a documentary called Food. Roots. Philippines., which he’s planning to finish by October for showing on PBS stations during Filipino American History Month, and on the festival circuit. (You can see the trailer here.)

“When my two elders died, I immediately got on the phone,” he explains. “I’ve filmed in the Philippines before, so I know cameramen, kids really, and they’re like yeah, yeah, we’re in, we’re in, just put a van together. We’re just traveling all over, learning dishes, and it became a lot more, because behind every dish, there were some serious stories about my family that just colored it in.

“And I’m learning about my name, and why I did some of the things I did in life. My grandfather, whose name I carry, was a small village community leader, worked his way out of poverty to get to Manila to go to law school, and then went back to his village. And I went to his house, and it was like a hut. My family was there from that lineage, and they gave me a goat and taught me how to cook it four ways.

“When I sat down after dinner to talk stories, I learned that it was a goat because they always had goats and chickens, because he helped everyone in the community and that’s what they gave him for money. And another cousin a little bit more south was teaching me this snail dish. And we’re just making it, lemongrass and ginger and coconut milk and all these different peppers. And I’m talking about how to source it. What do they usually cost, those peppers? ‘No, no, when we work the rice fields, we [pick them and] put them in a different bag.'”

He shakes his head at the realization of the differences between his world and theirs. “And I’m like, you’re my age, you’re almost my same DNA, we have the same Lola, and that’s what you do, still? You just grab them while you’re working the fields. I was learning recipes, but I was really learning shit about my family that was like, what the fuck.”

Family connections eventually led him to what he describes, a bit ominously, as a headhunting village on a remote island. “I went 2-1/2 days off the grid and found this 103-year-old tattoo artist in a headhunting village. Because I wanted to know what a village looked like, untouched, pre-colonized. And learn what those recipes tastes like. The coolest experience in the world,” he says.

“This lady, she doesn’t really tattoo any more because she can’t, but I told her my story, translator to translator. I told her how important it was to tell these stories in America, to know this even exists,” he says. “So she walked over to her big cauldron on the floor, with the fire and the char, and she grabbed the ash and the soot and put it in a coconut shell. And then she went over to this bush, grabbed a big thorn, and put it in a hole in a stick and tied, and then put the ash on the end of the thorn. And started fuckin’ jabbing me…” Words escape him at the moment, but I’ve seen a shot of it in the trailer, so he doesn’t need to make the process of tribal tattooing with a thorn on a stick any more vivid than it already is.

“And it wasn’t like America, where we’re like, ‘Uh, I’ll take the Harley wings,’” he laughs. “They decide what it is and where you’re getting it. But I could never have gotten that if I didn’t have my lineage, if I didn’t know the specifics of where they are from… it was just the greatest thing.”

Sisig with fried egg. “In a Filipino household, you put fried egg on everything.”

HAVING RETURNED TO HIS ROOTS AND divested himself of the businesses that no longer interest him, Billy Dec asks me what he should do with his life.

“I’m a free agent now,” he says. “This all just happened at the end of the year. I could partner with any of the groups, with any cool chefs.”

He tells me what he’s been thinking about doing. “I was really tempted to do a Filipino restaurant, small, with some really amazing chefs in LA. that want to do something together. And instead, I said, why don’t I help you do it—why don’t I help you guys with the infrastructure that I’ve learned the hard way?

“If I have access to the best talent in the Filipino world, do you think I’m being wasteful in not opening a small Filipino space?” I suggest that it would be a fine thing to do—but so is introducing a cuisine to the number of people who pack a place like Sunda, night after night.

He seems to be wrestling with the possibilities. “I want to do something really significant and I don’t know what it is. Is it a high quality fast casual concept, where we can pop it up in more areas? The whole restaurant model is really concerning me, and what kind of tweakage can we make to make it better? I just think the model is messed up. I think people are being derailed by things you can’t control. Like labor laws, wages, rents. And then there’s things you can control, whether it’s HR, rents, compliance issues. sexual harassment, training orientation, all the things that I’ve learned the hard way in all that time. And then marketing, how to differentiate yourself, tell your own story.”

He admits that expanding Sunda is “a full plate, and I don’t want to get back to the situation I was in where I overdid it. The idea of me being able to help other people work on their concepts, rather than it just being me and my four walls—I’ve been doing that for twenty years. I was grinding so hard for so long, I’m kind of happy to help with other peoples’ problems.

“The days of forcing things are over. I just want to do really meaningful, good things. Until it doesn’t work. Until I have to go back to doing it the old way,” he laughs.

I tell him he reminds me of talking to Michael Carlson of Schwa a couple of years ago. When you’re young, you like the party and you want to show the world what you can do and knock it on its ass. But Dec is 45 now, married for a decade and with kids. And if the party hasn’t killed you, your priorities change. It’s less about what you can do, about the creative disruption of your talent, and starts to be more about mentoring the next generation and creating something for the future. It seems like he’s making a natural evolution to me—and he should go with it.

Anyway, I doubt he really needs my advice, given how many possibilities he has going at once. He tells me about a meeting he had while he was filming in the Philippines. He had met the vice president of the Philippines while he was on one of the Obama panels, and she passed him along to officials of the tourism board. “They loved what we were capturing and sharing so much, that they said it would be great to do a series exploring the rest of the over 7,000 islands. We’re actually talking about it—we’ll see. I’ll be back there to visit my family again in January, either way.” The world, and certainly the Philippines, could use a new Bourdain; maybe that’s where the party and TV-ready Billy Dec are going next.

THERE ARE TWO DIRECTIONS FOR A RESTAURANT GROUP to go from Chicago. One is to other top level food cities—toe to toe in New York City, like Hogsalt is doing with Au Cheval. The other is to go to up and coming cities where a newly sophisticated audience will be excited to have Chicago food talent at work in their town. Which is how Nashville has become a bit of a culinary outpost of Chicago, and the first place Dec has sought to expand the Sunda brand.

“The concept [of multiple Asian food cultures] works in Nashville,” he says. “People know that they can get a mix of stuff if they don’t like raw, they don’t like spicy, there’s familiar items from familiar countries and then maybe not so familiar items. That diversity, people take to it.”

To make it work, Dec bought a house in Nashville, typically spending Sunday through Thursday in Nashville and the weekend in Chicago. He also persuaded some of his Chicago staff to follow him there, because Nashville is growing faster than restaurant culture can keep up with. “It popped so hard and so fast—150 people moving there a day in the last three or four years. They’re moving these companies with 500 or 1000 people at a pop,” he says. “And every time you do that, you need everything in life. The person who works at the store, the bus driver, the gardener—every single thing in life.”

I ask him if he sees a difference in the restaurant culture in the two cities. The biggest one: the workforce. “On the end of the night notes [in Chicago], very seldom, we’ll have, ‘Joe Schmo, no call/no show.’ That’s a bad thing, he didn’t call us or show up? He’s either fired or he quit,” Dec explains. “In Nashville, when we first opened, we had about two a night. I was lead bus boy, every night. Pouring water, clearing tables, table touching—which I loved, I hadn’t done that in so long, but that’s how I got started. And it’s such an awesome entry point to talk to people, sometimes you forget to talk to people—because we all shifted; chef’s on the line, the manager is expo’ing, I’m bussing.

“But no call/no shows and walkouts in Nashville, because of the labor shortage and the ability to get a job anywhere they want… You can walk in and be like, hey, I just left that really awesome restaurant across the street, I walked out mid-service, pay me a dollar extra? And I’d be like… yeah. Because I need somebody.”

One answer was to lure some of his Chicago staff to Nashville. “We were kind of bursting at the seams with talent here. No one ever left after eight and a half years,” he says. “I strategically took them in February and March, when it was freezing here. It was 75 and sunny, with birds singing songs, country singers singing—real instruments everywhere. No electronics, and the guy that made the guitar, the person who wrote the song is sitting right there.”

Next I ask him if he’s noticed any differences develop between the two Sundas. He says in Nashville, “The conversation’s different at the table—a lot of the agents and country stars and the small portion of people that travel a lot have had the flavors, but I introduce them to Filipino food and it’s like, what? Zero idea. But there’s a lot of commonalities between even Filipino culture and a lot of what I’ve experienced in Nashville. I mean, the amount of pork dishes that go out—they just happen to be Filipino dishes.

“The other thing that I think people are really digging is the Kamayan. They just freak out. It’s a very family thing, so Nashville gets that,” he says.

Kamayan—a recent addition at Sunda in Chicago as well—is a traditional Filipino feast spread out on banana leaves, which you eat with your hands from the table. “In January I did a family reunion in the Philippines,” he says. “And it was funny how normal [eating off leaves] is. It’s like laying out a picnic cloth. At our Kamayan meals at Sunda we give everyone a seat, let them take their time. We laid out a 40 foot table at this family thing, it was standup—and I immediately had to squeeze in, and things were flying fast, and it was fun and crazy and—I forgot, you know? I forgot how this is. And I looked at all the kids, and I’m like, man, that was me. I’ve been going back and forth, all my life.”

Michael Gebert is boss tao of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.