A PARTY OF FOUR LADIES OF A CERTAIN AGE, dressed up for a girl’s night out in bright colors and plenty of jewelry, is sitting at the counter, and I can tell they’re curious about the American family seated on stools next to them. The one closest to me finally just asks in English heavily accented by her native Japanese: “How are you at this restaurant?”

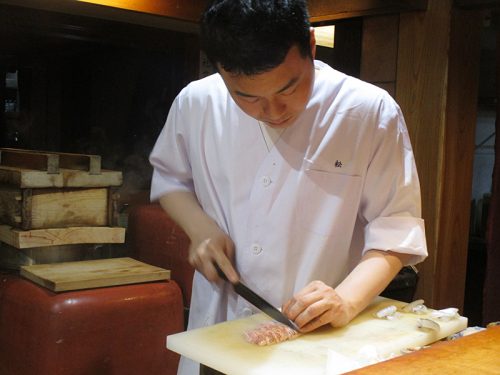

And it’s true that it’s an unlikely place to find Americans on a Sunday night—a roadside restaurant on the other side of Kyoto from the busy tourist areas, where restaurants make it easy by declaring “English Menu” in bigger letters than their own names. Behind the bar, an older man dips vegetables in tempura batter and then places them gently into a pot of boiling oil for just seconds before plucking them out with long pincers. At the other end, two long red urns radiate heat, one full of white-ashed bincho for grilling, the other topped with two wooden steamer casks. In between them, a young man expertly slices fish while maintaining a steady stream of joking and giggling in Japanese.

“The chef,” I say, pointing to the younger man, “worked in Chicago for a chef I know.”

“Are you chef?” she asks.

I briefly think that it’s hard enough explaining to my wife what I do these days, let alone to someone in a foreign language. “I write about food,” I abbreviate, pantomiming typing while I’m at it. “I know a lot of chefs.”

I think she gets it, but it’s hard to tell because at that instant, a block of ice is placed in front of her with a bowl carved into its middle, in which cold noodles sit in broth. Facing something so monumental suddenly delivered to her with the expectation that she eat from it, further conversation comes to a halt.

Toshio Matsuno

TEMPURA MATSU IS BECOMING A HOT FOODIE ticket, and those who’ve been take it for granted that it will rank among Japan’s Michelin-starred spots soon. But it’s not exactly geared up yet for the culinary globetrotting set, and my family is rightly a curiosity there. To get in, I’ve traded on a connection to Takashi Yagihashi, owner of Slurping Turtle and now-closed Takashi, but though I’ve shot video of Takashi a couple of times and met him a few more, my real connection here was Steve Dolinsky. An instantly-ardent Japanophile after his first trip in 2014, Dolinsky went on Takashi’s recommendation and wrote “your meal at Tempura Matsu will be life-changing, revelatory. It’s not molecular, and it’s not avant-garde. It’s simply Japanese perfection, using only what they can purchase each day, then combining fish, rice and a myriad of sea creatures into a tasting menu that you’ll be talking about for the rest of your life.”

It’s a ride with the chef in charge that seems closer to American dining at the moment—even as the techniques, and certainly the ingredients, are classically Japanese.

It’s interesting that Dolinsky almost instinctively called it a “tasting menu,” because it reminds me you of the pace and style of Chicago tasting menus—I’ve described it to people since we got back as “the EL Ideas of Kyoto,” for the informality and frequent laughter as much as the inventive dishes. But the menu of seasonal little tastes is something that Japan’s been doing for, oh, 500 years or so—most of Japan calls it kaiseki, and Kyoto, which I gather tends to think it’s the most refined place in a highly refined country, calls it kyō-ryōri, which just means Kyoto cooking, as if to say, of course we’re cooking seasonally, and arranging it beautifully, what do you do?

But this meal isn’t following the traditional order of kaiseki dishes, which progresses from sashimi to cooked dishes. Kyoto has plenty of those, following a decades-old book and charging Michelin prices for a technically perfect evocation of the season. Tempura Matsu is more like a tasting menu in Chicago, where the emphasis is on dramatic techniques and visual playfulness as much as flavor. It’s a show, a ride with the chef in charge, a parade of surprises in a way that seems closer to American dining at the moment—even as the techniques, and certainly the ingredients, are still almost all classically Japanese.

Tempura master Hirofumi Oyagi

All this, surprisingly, in a restaurant inside a house facing a highway and a river, named for a simple everyday food, tempura. Upstairs it looks like there’s slightly more formal dining, but downstairs it’s a bar with stools and wooden booths, the kind of tavern that could be in Wisconsin and named Stan’s Place or The Wagon Wheel. That’s the other part of this that seems like EL Ideas—it’s grown up inside a space that clearly didn’t start life as anything resembling fine dining. It’s a roadside family restaurant that’s charging three-figure sums (about $150 for dinner) and shooting for world-class status. How does such a thing happen in Japan, where dining gets more traditional the more money is spent on it?

Normally, I’d answer that question by interviewing the chef—but in this case, though Toshio Matsuno, the young, frequently laughing chef, speaks enough English to functionally get through explaining our meal to us, my attempts at exploring more philosophical concepts of cooking with him don’t really work. So for the history of the restaurant, I’m mainly relying on Rice Noodle Fish, a book about food in Japan from one of the authors of the Roads & Kingdoms blog, Matt Goulding, who devotes about 20 pages to Tempura Matsu—as the antidote to “a boring, overpriced cuisine in need of a shakeup.” Or as another blogger puts it, “It is strangely raw and real in a town that can be almost too elegant and refined to be believed at times.”

And though it’s by no means the only, or even the most important, influence here, I come away convinced that the two months Toshio spent in Chicago are one of the things you can see here that set it apart. Even if it means we’ve traveled halfway around the world to eat at the EL Ideas of Kyoto.

An uncharacteristically serious Toshio and his sister Mariko

WE HAVE A PARADIGM FOR FATHER-SON Japanese restaurants in Jiro Dreams of Sushi—the father so dedicated to the perfection of his art that the son is never allowed to blossom on his own, is doomed to hear “Well, it’s not what it was when Jiro was alive” for the rest of his career. Tempura Matsu presents a different one—an attempt to get out from under the heavy hand of Kyoto kaiseki tradition and follow one’s own creativity. A father’s plan for personal expression, that will span decades being realized by his son.

Toshio’s father, Shunichi, comes from Gion, the ancient district on the other side of the other river in Kyoto, which somehow manages to be both its spiritual center and its entertainment district. In early evening it seems the most restaurant-dense place on earth, as dining rooms in 300-year-old residences light up their foyers to welcome guests, and geishas (who were invented here) move in packs through the streets—is it merely for the tourists, like a Japanese Colonial Williamsburg, or is it because they still dress that way here? I’m not sure.

It’s all quite lovely, and there’s plainly an internal tourist trade for Kyoto as the place you go to have a storybook traditional dress wedding. But Gion was also the red light district of samurai days, and it’s not hard to wander into more modern streets and find nightclubs named things like Club Exotic, in front of which sit black Mercedes with glowering musclebound chauffeurs, waiting for the boss to finish inside.

Tempura

Shunichi wanted out of all of that, the heavy hand of history telling him what he could and couldn’t do as a restaurateur. So he set up his tempura shop on the other side of town, in the Arashimaya district, by a river and a bamboo forest—44 years ago, Toshio says. Within the first three years, his ambitions expanded beyond merely frying vegetables in tempura batter, and the menu evolved over time to reflect the range of kaiseki—in his own style.

His greater ambitions were for his son, Toshio. (Toshio has an older sister, Mariko, who is effectively the restaurant’s manager.) Shunichi taught Toshio what he knew, and then he began seeking other masters for him—like Alain Ducasse, whose Tokyo restaurant is one of the city’s most expensive and highly rated (assuming you go to Tokyo to eat French food). Toshio staged there in the late 2000’s.

At that time Takashi Yagihashi hadn’t come to Chicago yet—he was working for the Wynn Resort in Las Vegas. “I have a very good friend in Kyoto, and several years ago when I went back to Japan, my friend took us to Tempura Matsu,” Takashi told me recently. “Until then I didn’t know them. But I saw this food, which was very remarkable, especially for a family run restaurant, not a big restaurant. And I fall in love with the people.”

Bonito sashimi

Shunichi approached Takashi and said to him, “‘I have a very good son, following my career.’ Toshio wasn’t there that night. And he said to me, ‘Can I send my son to Las Vegas to learn?’ So I said no problem, and for a couple of months he stayed at my house” and staged in the kitchens at the Wynn Las Vegas.

A couple of years later, in 2009, the Matsunos approached Takashi about Toshio coming to Chicago. Takashi invited him for a stage at Takashi, but more importantly, set him up with stages at Charlie Trotter and Alinea during the same visit in November and December 2009. This is when he saw a more sophisticated American approach to simple, ingredient-forward and to some extent theatrical cooking—though when I ask Toshio what he came to Chicago for, he says “to learn French cooking.” Well, French technique underlay what both Trotter did and Grant Achatz does, however much they evolved it to something else entirely. Either one could have told him that you have to know your tradition, in order to escape it.

THE FIRST COURSE WE GET IS enough of a show that it could have come straight from Alinea—a little salad of a chopped clam with some vegetables and rice, under a dome of clear gelatinized broth. A scalding hot bowl is delivered to each of our places, and then the entire salad is placed into it, the gelatin bubbling furiously as the oyster and the rice fry in the liquid it creates.

There are dishes that you’re supposed to eat a certain way in Japan, from ramen on down. But a subsequent course of tiny shrimp on a block of vegetable (daikon or something in that vein) is the first one on our trip where I’ve been instructed, as with Alinea’s black truffle explosion, precisely how the chef wants me to eat it—first, drink the broth, then eat the shrimp and vegetable which have been warmed by it. It’s a terrific shrimp bisque, classically French—except it’s not; there’s no dairy in it, he tells us.

Oh, and speaking of presentation, we’re also told that the bowls it’s served in are about 300 years old; if you look closely at the plain black top, you can make out cherry blossoms lacquered under the glaze, 300 springs ago. Much of the servingware is antique like this, perhaps Shunichi’s way of reclaiming the heritage he moved to get out from under.

One course will be familiar to anyone who’s been to Next—though it’s an ancient Japanese way of cooking:

Rice Noodle Fish notes that Toshio, even as a mere stage, may have played a role in elevating this method of cooking to a place in international cuisine:

“I taught Ducasse how to cook on hot stones,” he says with a sort of sweet seriousness than dispatches any doubts you might have about the claim. “Now he’s using it in all of his restaurants, but because he’s so famous, people think we’re the ones copying him.” When Toshio looks over at me, he seems concerned that my pen isn’t moving. “Please make sure to write that down.”

Could be. What impresses me, though, is that for all that you can spot influences from Western dining styles poking out of our meal, the food remains strongly rooted in Japanese cuisine free of trendily shallow fusion tropes, the briny and woodsy flavor notes of Japan in almost every course.

Fish with its own skin crisped on top

And even more specifically, it’s rooted in the cuisine of his father’s restaurant. One of the most simple yet satisfying courses is the sashimi of a fish served with its own skin, flash fried, and accompanied by what he called “soy sauce with sea bream.” I don’t know what the latter meant, exactly, other than that the soy sauce had something (bonito-like flakes? roe? larvae?) mixed into it, but it tasted like soy sauce thrown back to a fishing village of a century ago. This is simple food with surprises of unexpected depth.

Soy sauce with sea bream… something

It ends, twelve courses later, with the showstopper we had seen the ladies finishing with, and laughing about, when we arrived: the block of ice with cold somen noodles floating in the bowl carved into the ice. We’re expected not only to eat the noodles out of it, but to pick up the block—which is not light—and knock back the rest of the broth. My kids, who’ve done me proud by eating more unfamiliar seafood in one night than in their entire lives to this point, are unfazed and happily lift the dripping blocks to slurp up the last bits of broth. They were in for the ride all the way, too.

ONE THING WE MISSED AT TEMPURA MATSU: Shunichi himself. Rice Noodle Fish talked extensively about the interaction of father and son, but in the time since the book was written—and since Dolinsky’s 2014 visit—Shunichi and his hostess wife have both retired and turned the place over to their children.

One who’s sure Toshio is ready to run the show himself is Takashi Yagihashi. “He’s such a great, great young man, he had a great time working here,” Takashi tells me. “He has a very good foundation working for his father, and his technique is impeccable. He has a very open mind, and he’s very hungry for something new. I enjoyed working with him,” he says.

Tempura oyster

I ask him what he thinks Toshio might have absorbed from his time in Chicago. He doesn’t mention anything on the level of specific dishes—”I don’t see anything that he’s doing in Chicago,” he says. “In Japan you can see new techniques and styles in restaurants becoming common.” In Tokyo I had a course in a restaurant where the plate was dabbled with dots and gels, and colorful, intensely flavored segments of fruits and vegetables were scattered about—that dish could have been from Trotter’s or any number of places, frankly. But nothing was in any way as obviously Western, or international haute-cuisine, as that here.

“Toshio is approaching it more like a traditional chef, do a lot of table side [preparation], more getting out from the counter and in front of the table side. I love it, it’s like French style, like crepes suzette,” Takashi says. “But he doesn’t do it in a way that’s completely changed [from Japanese tradition], I think he learned from many places and he gets so many ideas, but he also digests it himself. What he’s doing now, is his.”

Tempura Matsu, 21-26 Umezu Onawabacho, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto 615-0925, Kyoto PrefectureMichael Gebert has two very good sons who try what he feeds them, as editor of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.

I was fortunate to dine here 11 years ago. The food was fantastic. every thing you have described here is what i remember, especially the cold ice udon. I too knew takashi. I cannot believe this place has gone unnoticed for this long.