THE LAST TIME I WROTE A FULL feature story for this site, I was in the middle of my (still upcoming) book. That was more than three years ago, and thanks to COVID, I spent much of the past four years doing interviews via Skype or Zoom, first by necessity and then by habit. I was excited by the prospect of getting to hang out in a kitchen again, chatting up a chef to discover his approach and watching dishes come together.

But the world has changed. So the first thing they told me was that my exploration of Feld would begin by attending their weekly Zoom call.

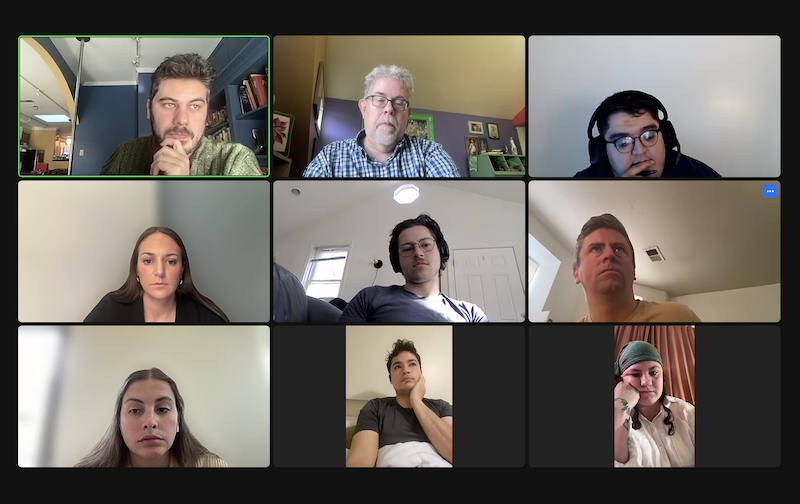

THE ZOOM CALL WAS AT 11 AM Monday—they’re normally on Tuesdays (service begins on Wednesdays) but this week they were having a holiday party for staff at Whirlyball, so it got bumped up a day. It was my first time meeting any of the staff, including chef-owner Jake Potashnick (upper left; I thought about making a joke about me having the Rose Marie square, but quickly decided that a 70s Hollywood Squares reference would simply baffle Feld’s youthful staff).

They knew each other and the current menu so well that I was soon lost in a host of references to things they were playing with—blueberry capers and maple mushrooms, saving the ash from burning last week’s scraps to nixtamalize chickpeas, a dish made with “cheese fat Bordelaise” which seems to have gone over well. The call was carefully structured, giving each cook a chance to bring up what they were thinking about, and Potashnick gave feedback, mostly supportive but occasionally cutting something off because it’s an idea that already didn’t work, or was repetitive of other things on the menu, or as he bemusedly explained, about something involving cheesy popcorn as a parting snack, “That’s a running gag, and they’re not going to get it just because somebody special is on the call.”

From the coverage of Feld—which has ranged from caustic to worshipful, depending on the moment—I had sometimes thought Potashnick might come off as a bit of a rube, young (he’s 31) and in over his head running a restaurant like this. But the chef I saw was decisive and assured, with a clear vision which he was happy to guide his staff toward, to help them refine their own ideas. Even when he shot them down, it was all good-natured, a little self-deprecating—at one point he called something “week one Feld,” ancient history and not good enough now, and someone else said they “missed the old Jake,” as in, they could have steamrolled today’s idea past him then, when he wasn’t yet the grizzled veteran (of five months or so open) that he is today.

They seemed a good crew who enjoyed working together. As someone who’s been immersed in the worlds of Jean Banchet (“Ah, the food will be good tonight,” waiters would tell diners when they could hear Banchet screaming at his kitchen staff) and Charlie Trotter (“He’s coming for you today,” Guillermo Tellez would warn cooks), Feld seemed like… a nice place to work? A supportive, collaborative environment?

That Friday, I would have the chance to find out for myself.

KING TRUMPET MUSHROOMS (FROM FOUR STAR MUSHROOMS), lacto-fermented and fermented again in maple syrup, then dehydrated; they were being painted with chocolate from Svenska Kakao in Skåne Tranås, Sweden, then dusted with flake salt and mushroom powder.

Alliums, that is, pearl onions (from Kankakee Valley Homestead), being peeled and trimmed; so were sunchokes (inevitable in fine dining in December in Chicago).

Chef Jake was slicing mussels thinly enough to be put on a slide in a lab, and arranging them in circle molds on parchment paper. These and other forms of prep were being performed, calmly and precisely, on the tables which extend into the dining room. It was one o’clock on Friday, and after Potashnick made his rounds to be sure everything in prep was going well, he sat down to talk with me.

The first question I’d been left with after the Zoom call was: the ideas being tossed about had sounded interesting, but what they didn’t sound like was a 30-course menu that was going to be ready a couple of days later—that is, tonight.

Potashnick explained that he saw the menu dividing naturally into thirds. “A third is something that’s set, it’s been on the menu for a couple of weeks. It’s tried and tested and true. These include things like dry-aged meats, that we have a lot of and we’re going to keep running” till they’re gone.

“Then there’s a third of the menu every week that’s just new, like this is a new vegetable that the farmer texted me is coming, or a new piece of seafood that our friends in Maine work with. And then there’s the third in the middle, which are things that maybe last week were new. This week, we’ve tinkered. We’ve adjusted them.”

So only ten things had to go from vague idea to finished dish within a couple of days. But whichever group they fell into on the menu, it was all driven by the state of the produce they’re getting that week. “When I say it’s a restaurant driven by extreme seasonality, people think that we’re changing the menu every day,” he says. “No, we’re driven by a product coming in, a product coming out. Because we work exclusively with a selection of farmers, if we run out of turnips, we don’t go find another turnip. It’s like, turnips are done.”

I asked him how he chose the farms he wanted to work with. “Well, it sounds obvious, but the first step is finding out about them,” he explained. “After I moved back to Chicago, I read about all the farms that go weekly to an accessible Chicago farmer’s market. From there I went and visited quite a few of them, and I asked the ones I liked who they liked. So now I’m learning about the network of which farmers support which farmers, often because they share farming practices and ethics. For instance, I work with Marty Travis and his farm collective Down at the Farms [Fairbury, Illinois]. Marty drove me and some of my team around to some of his favorite farms he works with, so we could meet those farmers. I’m not just ordering off a sheet from Marty each week.”

“After a visit—or two or three—I make the call on if I think it makes sense to work with that farm. I’ve had farmers at market stands lie to my face about their operation, something I only realize after visiting the farm. The visit is so incredibly important. There’s a lot of factors that go into deciding which farms we end up working with. I wish every farm could be Jerry Boone at Froggy Meadow. He’s my favorite farmer for both his product, and growing philosophy. But there’s only one Jerry.”

“So I have to make considerations for every farmer we visit. Are they growing in a way that I think is good for the soil? Are they avoiding sprays or minimizing any spraying that they have to do? Are we working with a variety of growing styles?”

“For instance, I enjoy knowing I have some farms with thick clay-soil and some with soil that looks more like desert sand. I’m not a soil scientist. I don’t claim to be. I care about the produce being grown and the person producing it. I care about the taste and the thought behind the growing method. I care about seasonality, and farmers who truly care about seasonality.”

Seasonality drives everything—most of all, when to boot something off the menu. “We kill our darlings quite often. And we also give ourselves a pretty strict rule of, like, no easy wins. Like a dish that’s just a cream bomb. Everybody loves cream. It’s like, how do we either make it more interesting or just get rid of it? Because that’s not what this is driven by.”

One easy win that’s avoided—loading up on the luxe ingredients that are perceived to justify the three-figure price at most tasting menu restaurants. (Feld, at $195, is around half the price of the most expensive tasting menus in town.) And the ubiquity of certain ingredients is, I suspect, a reason why some reviewers and hardcore foodies have gotten tired of tasting menus (more on that anon). Jake explained, “You’re not having truffles tonight. You’re not having caviar, you’re not having wagyu. You are having foie, but it’s from the most special foie gras farm in the country.”

Chef Jake with tonight’s duck; the paintings behind him are of Froggy Meadow Farm, near Beloit

“There’s three foie gras farms in the United States,” he continued. “There’s two in New York, La Belle Farms and Hudson Farms. La Belle raises 180,000 ducks a year, Hudson Valley raises half a million ducks a year. At Au Bon Canard, Troy King is a one man band. He raises 550 ducks a year. We wouldn’t serve foie for the sake of serving foie. We serve foie because this guy is so close. He’s near the border of Minnesota with Wisconsin [Caledonia, Minnesota], I can go visit him, I have a really good relationship with him, and it’s an unbelievably special product. You’re also gonna have the duck that that foie came from. So it’s like, I’m not serving luxury products for the sake of it. I’m serving them because they happen to to fit our philosophy and ethos and be delicious and be special.”

Potashnick’s description of his philosophy in a soundbite—”relationship to table,” which means not only that Feld has relationships with farmers but that they try to convey something about that relationship to the diner—is pretty good as marketing, but it’s also what has annoyed other chefs about Feld’s publicity. As one said to me, after we’d both heard about Feld (but neither of us had been there), “We all do that now”—not just buy from farmers but change the menu week to week, based on what certain farmers tell them they have.

That night at Feld, I had a dish with winter spinach (the cold makes it sweeter) from Three Sisters Garden in Kankakee—and the next night I had the same farmer’s spinach at Dear Margaret. So it’s something many restaurants besides Feld use—and it only exists as a farm because owner Tracey Vowell was a cook and sous chef at Frontera Grill, and Rick Bayless supported her evolution into a farmer selling to restaurants. The point is, plenty of restaurants have relationships with midwestern farmers, the same midwestern farmers, these days.

“We didn’t invent the idea of talking to our guests. We didn’t invent working with farmers,” Potashnick admitted, well aware of the criticism. “Yeah, everybody now works with a farmer, but also a lot of people just work with big name farmers who do big deliveries once or twice a week. That’s great, I would rather they do that than work with a big box operation—but this restaurant does not have a single contract with a US Foods or a Sysco. We don’t get things in cans. When they want to do staff meal with something in a can, I have to go get my personal can opener for them.”

It’s a determined, even proud commitment to doing things a certain way, a way that’s not unique to Feld but certainly taken very seriously. So where did it—and he—come from?

BUT FIRST, SPEAKING OF STAFF MEAL, that’s what we’ve stopped for. It’s a very nice gumbo; I was happy to share in their comparatively humble meal, to be able to claim that I had lunch at Feld (which they don’t serve) as well as dinner, but the risk is that it could wind up being the best dish of the day. (Awkward!)

I’ve heard a lot about Potashnick’s background, or what people imagine it to be, so I asked him to tell his own story. Though Berlin, among other metropolises around the globe, would come to play a major role in his background, he’s a Chicagoan—born and raised in Lakeview, or as he put it, “around the corner from The Bagel.” He loved food from an early age, and an eighth-grade science fair project proved to be pivotal in his life: his mom had just read a review of a year-old restaurant called Alinea, saying they did “science-y food.”

“I sent them an email. Grant Achatz responded and was like yeah, come on in. And he gave me a personal tour of Alinea. I mean, I didn’t get to eat there, but he gave me little bites of things. He gave me a bag of maltodextrin”—the fat and flavor-absorbing powder ubiquitous on “molecular gastronomy” plates c. 2007—”for my project. But the science-y stuff wasn’t what was fascinating to me. It was the rows of, like, everybody in all white, and it’s so quiet. I was just like, why would anyone not do this for a career?”

He goes, ‘I don’t really care if you learn how to cook by the end of this. I care that you know what a real carrot tastes like.’

“I went to college in upstate New York for business, and then I went to the Cornell hotel school,” he continued. “Every summer, when all my friends were interning in investment banks or consulting firms, I would intern in restaurants. I picked a bunch of different kinds of restaurants—two stars, three stars, no stars. Because I wanted to know, what do I like?”

Part of the criticism of Feld has revolved around him not having a track record in Chicago restaurants—and Chicago is still a place that don’t want nobody nobody sent. But actually, that first summer after college, he worked for two chefs who epitomized the kind of Chicago dining that breaks rules and boundaries—he worked for Homaro Cantu at iNG, the sibling of Moto that did things like heavy metal-themed tasting menus, and he worked for Philip Foss at EL Ideas. “Props to Chef Foss, he sat me down after that summer and he said, what do you want out of your career? I said I want this and this and this. And he said, You don’t want to be the cook who makes the rounds of all the Chicago places. You need to go explore, and then come back. By pure chance, I had applied to a restaurant in Sweden a week before that. I heard the next day, and three weeks later, I moved to Sweden.”

The restaurant was Daniel Berlin Krog, in the southern Swedish town of Skåne Tranås, which was just coming into its own as an internationally recognized spot—this piece at Bon Appetit, calling it “the restaurant you need to visit right now,” came out just a couple of months before Potashnick arrived in September 2015. During the year and a half he was there, “It got its first Michelin star, it got into the back end of the 50 best list. When I got there, there was Daniel, there was Eric who was the CDC, there was Alex who was the sous chef, and there was me, that was the whole team. By the time I left, there were four stages and another cook. I watched this place balloon up in success.”

“Daniel’s the best. He was the best mentor. He sat me down on the first day, in the greenhouse where they would take guests for desserts. And he goes, I don’t really care if you learn how to cook by the end of this. I care that you know what a real carrot tastes like. He was just obsessed with produce. And the only meat we really served in that restaurant, at least in the autumn and winter, was what Daniel hunted himself.”

After a year and a half, he went to Japan for three months. “I spent a month apprenticing in a place called Narasawa,” a two Michelin star kaiseki restaurant, “and then a month in Kyoto at a place called Kichisen, which was like super traditional kaiseki. It blew my mind, and their work ethic blew my mind too. While I was there, I got a job offer in France. So I flew straight from Japan to France and started working at this place called La Marine,” on the tip of an island off the west coast of France below Brittany, dotted with the getaway homes of wealthy Parisians. La Marine holds both three Michelin culinary stars and a Michelin Green Star for its commitment to local farmers and fishermen.

“Daniel Berlin was the kind of restaurant where it was a three-month menu. You did not change it for three months. La Marine was a place where, every day Alex [Couillon] scribbled out the menu for the day. We would go pick the vegetables from the garden in the morning. We’d get the fish the night before, and that’s what we would make the menu out of every day. And it was just like, so freeing.”

For his next position, “I wanted to find somewhere that kind of kept to that trend.” That brought him to the place that you’re most likely to hear mentioned as an influence on Feld—”this tiny little restaurant, which at the time was six months old, called Ernst in Berlin. I visited Berlin as a tourist a bunch, and I loved the city, and reached out to them. And they were like, Sure, come eat. You need to come eat before you’re allowed to work here. They were super strict about that, because, they said, people find this restaurant divisive.”

Curiously, especially as I got hints of dry German seriousness, a whiff of Sprockets, from the way Potashnick talked about earnest Ernst, the nine-seat restaurant was not actually run by Germans or German by cuisine—chefs Dylan Watson-Brawn and Spencer Christanson are Canadian, and if they claim any country as inspiration, it’s Japan. Jake said, “They ended up in Berlin because Berlin is also the techno capital, right, and the electronic music capital, the super modern, contemporary art capital of Europe. I think Dylan could see that that was a place that would be accepting of what his cuisine is, which is extremely minimalist. I mean, bizarrely minimalist, and I do think it was embraced for that reason there. I don’t think that restaurant works in Munich or Frankfurt or Dresden.”

Feld is maybe not bizarrely minimalist, at least now, but as Potashnick talked about his experience at Ernst, you could certainly hear the inspiration—even as he denied too close a similarity: “If Dylan came here, he’d be like, this is not our food. He’d be mad if we called it that.” But one thing he got, certainly, is the thing no one thinks about German cooking—a close connection to farmers. “There’s a shockingly good amount of farms and produce [in Berlin] because, all credit to the Eastern bloc, [the culture there is] driven by the base mentality of that mindset, because Germany was divided for so long.” At the same time, the restaurant culture has only slowly moved to a widespread acceptance of anything farm to table—”Here we have a million great farmers markets, and it’s pretty easy to go up and talk to a farmer and start chatting with them. In Germany, it’s so difficult to get a farmer to trust you, because they’ve been scorned by restaurants in the past.”

I know one of the critcisms of Potashnick is that while he’s staged all over the globe—Eater said “At 30, Potashnick’s resume borders on ridiculous”—he’s supposedly a dilettante who’s never really worked anywhere. Potashnick refutes that notion forcefully: “I think part of that comes from [the idea] that I’ve never really worked in Chicago. I worked at Daniel Berlin, I worked at La Marine, I worked at Ernst, I was head chef at Barra [a nose-to-tail restaurant in Berlin], all for a minimum of a year, and some of those up to two. By the time I left Ernst, I was the most senior employee there, and was very much creatively evolved, hierarchically involved. At La Marine, I was hired to replace the sous chef, because [Alex Couillon] had a lot of respect for Daniel, and he wanted somebody to come who was coming from Daniel Berlin, and he instructed me to start a fermentation program.” He sighed, “That’s one of the critiques I don’t really know how to respond to in Chicago.”

WHEN CHARLIE TROTTER FIRST OPENED HIS RESTAURANT in 1987, with a sign handpainted by his sister Anne in the window, he was nobody and nobody knew what it was, and he had time to work out the details.

Decades later the restaurant world is very different—and Jake Potashnick has had to play under the new rules of restaurant publicity. Feld has lived through at least three distinct phases of public awareness. First, Potashnick used social media to get his name out there—primarily his TikTok and Instagram accounts, in which he expressed his philosophy and built up an audience. (He also wrote lengthier disquisitions on Medium.)

The second phase began when Feld opened on June 28—Week One Feld, so to speak, and the few weeks after. People shared their experiences on Reddit’s r/chicagofood—and some of the reports were not friendly. Like the one headlined “Went to Feld. Hated it, thanks for asking,” from the first week or two. The photos accompanying it came in for particular scorn, minimalist plops of stuff in a bowl, or most notoriously, three slices of cheese, laying on the plate vaguely like a collapsed Stonehenge. That’s a course?

In that first month Feld also got its first review from someone who has actually been a mainstream media reviewer—Michael Nagrant. In a Substack review dated July 26, he engaged with the restaurant seriously—after sharing his own version of the Cheesehenge photo, he actually spoke appreciatively of the concept behind it:

It is actually the very best dish Feld serves. The cheeses from Uplands were made last year on successive days of July 11, 12, and 13. The concept of the plate represents a year and a half of planning, a pilgrimage to Wisconsin and a plea with the cheesemaker, offerings of coffee and donuts to convince him that Potashnick wasn’t crazy.

On the other hand, Nagrant’s review contained the phrase which would stick to Month One Feld like white on rice: “Food-wise this is the worst meal I’ve experienced in nineteen years as a food writer.” It’s safe to say that not only did he not respond to Feld’s concept, he had to contact Potashnick afterwards to try to understand what it was supposed to be. He also observed what some of the Reddit commenters had noted: seasoning was inconsistent at best, nonexistent at worst.

It’s fair to call this (along with The Infatuation also reviewing it pretty negatively in the first few weeks) Feld’s low point, and Potashnick still has sensitivity to it, complaining to me about reviewers (unnamed) who review your restaurant too soon. True enough, but tell it to Charlie Trotter—you can’t, because you just don’t live in the world he knew, where foodies and reviewers alike gave you time to find your way—gave themselves time to discover you.

On the other hand—and you might not know it from Potashnick occasionally kvetching and kvelling on Kvinstagram—he seems to have reacted intelligently to the complaints: the seasoning is on point now, the plating, though still deliberately unfussy, doesn’t look quite as random as it once did. “We did not design the lighting in here for food”—or for foodies taking food photos, he explained. “We designed it for the experience of being in here. We use the term ‘manicured plates.’ How manicured do we want our food? We’ll do something if we think it makes it taste better. So you’re gonna have dishes tonight that are more plated, more refined, sharper, just by default of the skill set of the team after five months. We don’t swoosh, we don’t dot. But also, most of our plates here are three to four components, so there’s not much to cover up with swooshes and dots.”

Which brings us to the third phase of Feld’s development, the one it’s in now. It’s perhaps best summed up by the fact that two food writers who’d been, described their experiences to me in almost identical language—or tone of voice: “Actually, I kind of liked it.” Said a bit uncertainly, gunshy, as if they expected to be instantly mocked (three slices of cheese on a plate! Imagine showing that to Curtis Duffy!) But the corner has been turned—Feld has had to work out its kinks in the glaring spotlight of online food chatter, but the consensus of those who’ve been lately seems to be that it has. Potashnick dated it precisely: “This restaurant has not received a negative comment from a single human to me, online or anywhere since like August, three weeks after we opened, four weeks after we opened.”

ABOUT AN HOUR BEFORE SERVICE WAS GOING to start, Feld, like all fine dining restaurants, was having a pre-shift meeting. Nothing particularly dramatic to write about came up in it, which was a good thing. The afternoon had gone by with no screaming or anything crashing to earth, nobody getting pissed enough to walk out (or at least sneak out to smoke a joint—Feld,has a strong no-substances-at-work policy).

They’re a tight-knit group—most of them are from outside of Chicago and moved here to work at Feld, so there’s no “when I worked for Grant/Paul/Stephanie, we did it like this…” They joked around a little, but never with a mean spirit. And it was clear that Potashnick set that tone; as I told another restaurant owner a few days later, “I don’t know if he’s a great chef, but he’s a really good boss.” He told me something that’s almost unprecedented in restaurant kitchens: since they opened almost six months earlier, they’ve added a couple of people, but no one among the kitchen staff has left.

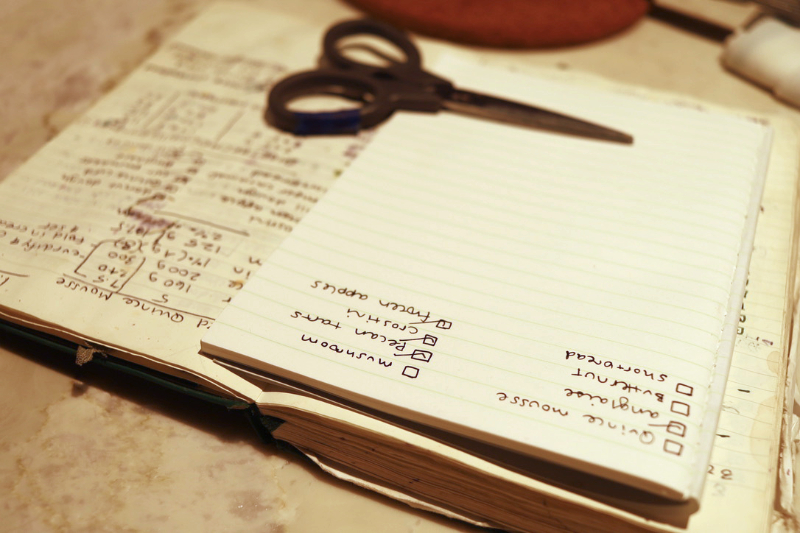

One thing here, that I’ve never seen so much of in any other kitchen, is that they all scribble in little notebooks. I suppose that’s essential to sanity in a place where you have (at minimum) ten new dishes a week. But it also hints at something about the way they work here: Jake may be on his journey, dish by dish, but so are they all. Remember what you thought of the dish you made today, because it’s going to inform how you approach whatever comes in next week.

Seven o’clock approached, and people started walking in the door. It’s maybe the coldest night of the winter so far, and Jake told me later that they’d only had three no-call/no-show parties ever, and two of them were this night and the (very cold) night before. (Hey, we’re Chicagoans, we’re supposed to be tougher than that.) I’m joined by my friend and fellow food writer David Hammond; picking a dining companion, I thought he would be open to the spirit of experimentation here (meaning if it was bad, he’d take it philosophically) and might offer a second perspective as we worked our way through the dishes. (We were both guests of the house.)

The tables are banquettes facing inward, toward the counters where most of the plating happens and behind them, the tiny kitchen. I’ve heard several times how dinner runs at Feld—30 courses in about 2-1/2 hours, each prefaced in some way by a little spiel from whomever is dropping it at our table. I didn’t want to drink a full pairing (hey, I’m working), but I asked him if I could get tastes of the pairings along the way, to see how that works too. So every course, and every pairing (about one for every three or four dishes) got an introduction. Sounded like a lot of food and a lot of talk.

It was, but it moved swiftly—after an amuse-bouche of polenta in amazake (fermented rice), which had a comforting corn taste, we got the next four all at once—raw trumpet mushrooms (not the maple ones) on a crostini, tempura-fried ones with dots of something (I was told there would be no dots), a duck confit pancake topped with a thin slice of radish, and a small bowl with two mussels which looked, unavoidably, the feminine opposite of phallic (I looked up the word for it, it’s apparently “yonic,” but neither of us would know what I meant if I used it).

Gold Bouchot mussels with dill oil

We started, as tasting menus tend to, with seafood courses; our second, less yonic dish of mussels was the paper-thin slices of mussels Jake was slicing earlier, tossed with a dill oil and, I think, something acidic. The gumbo is safe—Hammond and I were both wowed by this mussel dish, and at the end, it was still the best thing we ate, or at least the one that we could remember the clearest, thirty courses and many tales of this vegetable coming from this farmer later. It being the dead of winter, we got many root vegetables—Hakurei turnips, sunchokes, fennel, a dish called “Parsnip—Spruce,” and beetroot with the cheese Bordelaise (the cheese provides the fat of the Bordelaise sauce, but beyond stating that fact, I have no idea how it’s made). It came to its savory climax with the foie gras with alliums, and the rest of the duck followed in the next course.

Foie with alliums

The meal flowed just as promised, quickly and smoothly; there was never a wait for the next course. Part of that was because, given the not-too-fussy philosophy on plating, there wasn’t a lot of time used up tweezering little microgreens into position. One sprig of dill on a course of fennel in lobster hollandaise was about as artful as that got. When I asked if they even have tweezers, he said yes, but I’d already seen the only thing they were used for—portioning out finely grated garlic for later use in a dish.

Fennel under lobster hollandaise with a sprig of dill

It ended with dessert, including those chocolate-painted maple mushrooms, and a course using Uplands cheese from Dodgeville, Wisconsin, not our old friend Cheesehenge, made from the hard cheese Pleasant Ridge Reserve, but parsnip ice cream plated with a cheese I nearly always run into around the holidays, the funky, Camembert-soft Rush Creek Reserve. (Hammond and I have history with this cheese.) And then after that there was another dessert experience (it’s waafer-thin!) which I won’t describe. If you haven’t already read about it, I’ll let it be your surprise; myself, I was far too full to wish to indulge in it.

Though there was someone standing in front of our table delivering and explaining a dish, it seemed, about half the total running time of the meal, I can’t begin to remember everything that was said, or even everything I ate. But there was so much continuous activity that I was certainly never bored. Service was, to use a cliche that’s almost never literally true, flawless. (The restaurant was, let us remember, five months old at that point.)

Maple mushrooms, Grandma’s shortbread, pecan potato pie

At the end of it Jake, taking a victory lap in the face of our obvious pleasure, said “So, worst meal in nineteen years?”

“Nowhere near nineteen years,” I joked back, and thankfully, he laughed.

WITH FELD IN ITS THIRD, ACTUALLY-I-KIND-OF-LIKED-IT phase, the critical consensus is moving to the idea that Feld is something special—Louisa Chu, reviewing it just before Christmas in the Trib, said “it has surprisingly become one of my favorite dining experiences”—as well as something to use to criticize the ubiquitous tasting menus around town. John Kessler posited that notion in Chicago mag:

There are more tasting menus than we can or should review in this magazine lest we give short shrift to the other 95% of worthy restaurants. Plus, most of them are showcases for a chef’s technical prowess, eye for creating visual drama on a plate, and storytelling as much as their palates. Yet one exception, which I reviewed last month, is the restaurant Feld. Like it (which I very much do) or hate it (which a lot of early visitors did), this Ukrainian Village spot and its chef-owner Jake Potashnick are really trying to do something new enough that it changes the conversation.

So it’s the antidote for people tired of tasting menus. But is anyone, besides a reviewer who has to decide which tasting menus not to write about, actually tired of them? I’m surely in the upper quintile of tasting menu devourers, and I’ve certainly grown tired during a few that just didn’t measure up, but I can’t say that indulging in a couple of examples a year leaves me tired of the format itself. (That line of Kessler’s about what Feld is the exception to? It all sounds pretty good to me!) But I can see the idea that presently, it’s at a less mindbendingly creative point than when, say, Alinea, Schwa and Moto squared off in the early 2000s, or the mid-2010s when Grace, Smyth and Oriole battled royale.

So I don’t see it as the solution to a problem I don’t have, but I can see it being the back-to-basics answer for some burned out on the genre, I guess. That said, 30 courses (27, by the count of the printed-out post-dinner menu) can’t help but blur together a bit: I can identify most of the early, seafoody courses by name, but had to inspect my photos minutely for clues what some of the later ones were. A lot of bowls of a root vegetable in a Japanese broth or a French sauce. When a (foie-based, I think) canelé turned up, it was a pleasure to see that Feld knew about baking, too.

Part of this is, I think, just the time of year; I think Feld would seem a very different experience in August, with tomatoes and corn and basil on the menu. The rigorous commitment to a small set of selected farmers and what they have this precise week, by the end, seems rather austere, and kind of German to me. (I note, and you can decide for yourself what it means, that two of Potashnick’s top influences are not currently in operation; Daniel Berlin has closed his restaurant in Skåne Tranås and opened other restaurants, and Ernst is apparently on hiatus. So it’s an open question how long such minimalist concepts are meant to last.)

But hey, Feld is a mere six months old by now. And thinking that it’s passed through three phases and is now fully mature, and set on its course forever, is almost certainly selling Potashnick short. I think back to my first visit to year-or-so-old Charlie Trotter, nothing conceived or plated in the ways that would become world-famous once every chef on earth had Trotter’s books (still five or six years in the future at that point). Trotter had European inspirations—Frédy Girardet, in Cressier, Switzerland, most of all—but in time he wasn’t just doing French nouvelle cuisine, but his own American vision of a similar philosophy. With luck and time, Potashnick too has the opportunity to take what he learned at Ernst and all the others, and follow it in his own, very Chicago and midwestern farming, direction.

Michael Gebert has had more courses than that once as editor of Fooditor, and it nearly killed everyone at the table.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.