1. Cooking From Books

“IF YOU WANT TO FIND OUT WHICH RECIPES in a cookbook to use, hold it up by its spine and shake,” says Tim Graham, executive chef and co-owner of Twain in Logan Square. “The pages that fall out are the ones that deserve your attention.”

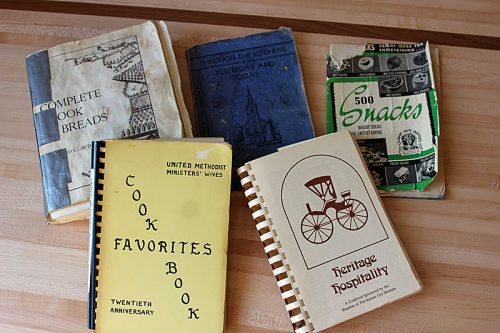

A focus on books from the midwest fits Twain, named for the author from Graham’s home state of Missouri; he opened the restaurant in August with his wife, sommelier Rebekah Graham, and partner, Branko Palikuca. The 41-year old veteran of Tru and Travelle has been collecting old, mostly Midwestern cookbooks since he was a teenager, and that collection, which numbers about 300 by now, is the backbone of his first independent venture.

Recipes from the books, mainly from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s, show up directly on Twain’s menu. But more importantly, it’s Graham’s passion for them and the culture that produced them that informs his whole vision for the restaurant, from the design by Jordan Mozer & Associates evoking folk art to the presence of hand-churned ice cream, made daily, on the menu.

His collecting focuses on spiral-bound volumes, many of them put out by women’s leagues, church groups or in conjunction with home economics courses. He says the tactile sensation of opening them and looking into the past fills him with joy. “I know it’s a romantic notion, but I feel connected to a time and craft that’s outside my purview,” he explains.

“There’s a naïve quality to the recipes, and many have the name of the person who created them written next to them. So it’s almost as if the sage-like wisdom of those people is being passed down directly to me, and I’m conscious of touching the same things they did. Then all of a sudden I’ll stumble on a hand-written note that really reaches out to me.”

Rebekah and Tim Graham at Twain

GRAHAM CAUGHT THE COLLECTING BUG after his parents started an eBay business called 50s Funk. He’d often accompany them on buying expeditions to flea markets. “I guess I gravitated towards books because I always liked them and history,” he says—“and I could afford them.”

Happy memories of special dishes for family celebrations—his aunt’s cheesy potato casserole, his dad’s seven-bean soup, his mom’s stacked enchiladas—helped focus his collecting on food. So did his father’s embrace of the “bread machine era” in the 1990s. “I’d walk into the house, and it would smell of freshly baked bread,” he recalls. “When I got an apartment with an oven in college, I always baked bread. I’m not sure why, but I loved it.”

The photo caption says “Almost anything you like can be rolled in bacon.” That guides my spirit.

Graham’s first cookbook purchase was “Bernard Clayton’s Complete Book of Bread,” and he still has it. It’s not spiral-bound, and the binding has been repaired with duct tape, but the recipe that falls out is for Egg Harbor Bread. “I’ve probably made it a gazillion times,” he admits, and it’s on the menu. He adds that he hasn’t modified Clayton’s ingredients or instructions for the fine-crumbed, dome-shaped white Amish bread that rises five times and is then baked in a loaf pan. The only difference is that when he’s kneading it, his hands “know better now than they did initially what’s happening in terms of temperature and humidity.” He serves mini loaves with pickles and pepper spread.

Graham doesn’t remember his first spiral-bound acquisition, but one of his most treasured is “500 Snacks,” number one in a 20-part series put out by the Chicago-based Culinary Arts Institute in 1940-1941. “There are no items on the menu from it, but it went to culinary school with me,” he says. “Curiosities like the two-ingredient bacon rolls are priceless. The directions are to spread eight strips of bacon with peanut butter, roll, fasten with toothpicks, and broil. The photo caption says ‘Almost anything you like can be rolled in bacon.’ That guides my spirit.”

Gallery: Midwestern Food and Drink at Twain

OFTEN GRAHAM WILL USE A RECIPE FROM one of his books but adjust it for a professional kitchen with more flavors and better ingredients. For his mushroom turnovers, for example, he’s kept the cream cheese crust exactly as it appears in “Heritage Hospitality,” sponsored by the Musettes of the Kansas City Museum and inscribed “to Bettye from R.J.W. 1983 Happy Mother’s Day.” But he’s changed the filling. “The recipe calls for canned chopped button mushrooms, which are one of the worst canned items ever,” he says. “I substitute porcinis and flame them off with Madeira, though most of the other ingredients—butter, onions, dill—remain the same. If a recipe calls for canned cream of mushroom soup, I never use that, either. I always make fresh.”

Another of his favorite techniques is to re-purpose a classic recipe. Calico salad, always a bean salad, turns up in about 10 percent of the books, he says, but he uses the version in the “Missouri Square D Cookbook” (Square D is a giant electrical company) and not only updates it, but also pairs it with seared Minnesota walleye and finishes the dish with pickled egg sauce. His salad has pinto and black beans cooked from scratch rather than the book’s canned, as well as cauliflower, broccoli, peppers, onions, and green and yellow beans, again all fresh.

“To get the right flavor, they’re marinated in the refrigerator for a couple of days in a mixture of vinegar, sugar, water, and a little oil,” he says. “But I don’t marinate the green beans with the rest because they get icky. I also delete the sugar—as I do from all the dressings in these books, because they’re always too sweet.” His attempts to “fancy up” the dressing with Champagne vinegar haven’t worked, so he sticks with distilled white vinegar. The other accompaniment, the pickled egg sauce, “is just my riff on the pickled eggs you’ll often find on a country bar in Missouri,” he notes.

Other menu items reflect dishes Graham grew up with, some of them ubiquitous in the Midwest. “Ants on a Log is more from kindergarten than a book,” he admits, “but I replace the peanut butter in the celery with a duck liver and peanut butter mousse, and the raisins on top with bourbon cherries.”

His Brock’s Fried Green Pepper Rings, on the other hand, are a tribute to Murry’s, a 33-year-old restaurant near where he lived in Columbia, Missouri. “I never met Brock (the menu has lots of dishes with people’s names attached to them), but the place is famous for these,” Graham says. “Ours probably are a little better than the original because we fry them in tempura batter, but the key is the copious amounts of powdered sugar dumped on them. They’re like funnel cakes with a piece of vegetable inside.”

Sommelier Rebekah Graham isn’t tailoring her wine, beer, cider, and cocktail program to go with specific menu choices, but she does see her 24 Carat Punch–a takeoff on the Golden Punch in those1960-1980 cookbooks that include alcohol–as a good match for the fried green pepper rings. She’s transformed the mix of pineapple and orange juice with seltzer water and Champagne into a rum-based cocktail with house-made pineapple cordial and orange flavors (essential oils, bitters, and liqueur).

“We also have the Jam Jar, a rotating cocktail with different jams and jellies (which will eventually be made in house) as the base, and a very traditional Sconnie, a Wisconsin-style Old Fashioned made with brandy and topped off with Sprite,” she says. “Mostly we want to find the right balance of beverages people are familiar with, and new ones.”

Graham’s cookbook collection continues to grow, and he’s created a spreadsheet to catalog it, assigning each book a number and referencing the page of each recipe he uses. “When my dad discovered he could buy in bulk on eBay, he focused his search on the Midwest and got me a lot—without West Coast riff raff,” he says. “In opening the restaurant, I’ve also received some wonderful presents.”

But the best gift, he says, is his own Grandma Graham’s cookbook put out by the Ladies of Saints Peter and Paul Church in Seneca, Kansas, in 1944. “I think it was a wedding present to her,” he says. “When I opened it up and looked at the first recipe, I saw that she’d crossed out a ‘scant 3 cups of flour’ and written in ‘2 ¾ cups of flour.’ She was a pretty rigid person, and that was typical of her. In that moment, I felt like she was standing there right next to me.”

2. Designing From Books

The Duke and the Dauphin, from “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”

WHEN RESTAURANT DESIGNER JORDAN MOZER REREADS “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn,” as he does every couple of years, he says he’s transported to being a 7-year-old boy down in a ravine looking for bugs—and struck by the novels’ archetypal characters and its celebration of everyday life and humor. That’s the same sensibility he brought to the design of Twain when Tim and Rebekah Graham explained their concept’s roots in midwestern cookbooks.

“The cookbooks are the quotidian documentation of Midwestern food culture,” explains the founder and president of Jordan Mozer and Associates, who made his name with the wild designs he did in the 1990s for Vivere in Italian Village and the Michigan Avenue Cheesecake Factory—which are like nothing you’d ever see in Hannibal, Missouri. “Like Twain’s writing, the recipes are timeless and transportable to any time and place. They’re made with everyday ingredients, and Tim has added his magic to transform dishes like chicken and dumplings to tell our story as Midwesterners. My job was to create a portrait of the Grahams’ ideas incorporating their love of barn quilts and other folk art, relying on locally sourced materials and hand-crafting as they do for the food.”

After meeting the Grahams through mutual friends, Mozer read Twain’s autobiography with Tim, and they also talked about the chef’s recollections of his grandparents’ farm. “I essentially blended Twain and Tim’s memories together,” he says, “and referenced them in everything from the pairs of bobwhites—a Missouri game bird and a Graham family favorite—and ‘Twain’ sign with honeysuckle blossoms, Missouri’s state flower, to the 60-foot-long dining room mural adorned with animals and landscapes associated with life along the Mississippi.”

Felt mural

That mural, made of 100% wool felt quilted with a nail gun, features a pink cow, an electric-blue heron, a purple donkey, game birds and squirrels rendered without perspective as a folk artist would. It was designed and built by Mozer’s eldest daughter, Eliza.

In fact, the whole project was a family affair. The patchwork “quilted” copper murals behind the bar with more creatures from Twain and Tim’s childhoods were designed and manufactured by Chloe, one of his twin daughters, as was the façade. The other twin, Isabel, did the graphic design for the menus. Mozer’s wife and business partner, Karen, helped with the interior design and was responsible for many of the finishes.

Jumping frogs from Calaveras County

More than 100 artisans and manufacturers were involved in making the patterns, casting metals, crafting the steel and wood components, and installing different forms of recycled and repurposed materials. Their handiwork can be seen in details like bar shelves carved from recycled red West African ironwood (brought to Chicago for highway partitions 60-some years ago), or the curving arches carved and cast in recycled metals to suggest Harold Fisk’s 1944 historical map of the Mississippi River. Chandeliers made with cloud-like wool and hand-blown glass shades allude to Twain’s birth, which coincided with the appearance of Halley’s Comet, and his accurate prediction of his death on its next pass by, 75 years later.

A structure that started out as a dilapidated 1920s garage was entirely rebuilt, from re-framing half of the roof to pouring new concrete floors and installing new doors and windows. One thing that wasn’t changed: The height of the interior—12 feet. “That was an auspicious height for a Twain concept,” Mozer points out. “As a 21 year old, Samuel Clemens became a licensed riverboat navigator. His job was to call out to the captain ‘mark it twain’ to indicate that there were two (twain) fathoms of depth ahead required for the safe passage of a river steamboat.” For those who don’t know, a fathom equals six feet.

Anne Spiselman is a freelance writer who has covered food, wine, and culture for decades. She’s a frequent contributor to Crain’s Chicago Business and Edible Chicago and has written for most local publications and some national ones.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.