YOU MIGHT LIVE IN A HIGH-rise, far above the city, and work in another just as high. You might not know your neighbors; you might celebrate the holidays alone, or with someone you met who, like you, is from somewhere far away. You might be a leaf in the wind, blown from one city to the next.

But the promise of Chicago is that out there, there are people not like that. There are people who grew up in a neighborhood known by the name of its Catholic parish, and have a tribe—Italian, Irish, Polish, whatever. And it comforts you to know that somewhere out there, this is a city where somebody gets a hundred friends together—a hundred friends! Imagine knowing a hundred people, outside of your office!—to make Italian sausage in their garage on a chilly Saturday. Italian sausage, from a 60-year-old (at least!) recipe passed down from a grandfather who was one bullet on D-Day away from losing it forever. You don’t know anyone like that, and yet it’s comforting to know that somewhere out there in Chicago, they still exist.

And they really do.

This year even has a T-shirt, modeled by Sam, great-grandson of Dante D’Apice, whose D-Day hat he’s wearing.

EDISON PARK IS A PENINSULA OF Chicago extending into northwest suburbs like Norwood Park and Niles. It’s no trick to tell what the ethnic makeup here is—any business not named something like Nonno Pino’s is named something like Emerald Isle. Public transportation up here means Metra, not CTA, and the houses are square brick buildings on spacious lots, prewar suburbia. Right now, it’s a rare house that hasn’t got a green election sign for someone with an Irish name in its yard.

But the story actually starts at the other end of Chicago, in Chicago Heights near the Indiana border. As long as Dan Schrementi can remember, his grandfather Dante D’Apice made sausage in his home, usually sharing duties— and the results—with a neighbor who like to make wine. Some of it would be cooked up fresh, but “the main part of it, you’d hang it, and make ‘super sod’ out of it,” as south siders call sopressata, a classic style of Italian salume. There’s enough regular salt in it that it would cure without spoiling, so they’d hang it in the garage. “I would always hear these stories of, one time they had a hundred pounds hanging up, and him and his neighbor would battle over who was in charge of opening and closing the garage door at certain times of days. A freezing storm is coming and somebody has to race home to close it—I love stuff like that,” Dan says.

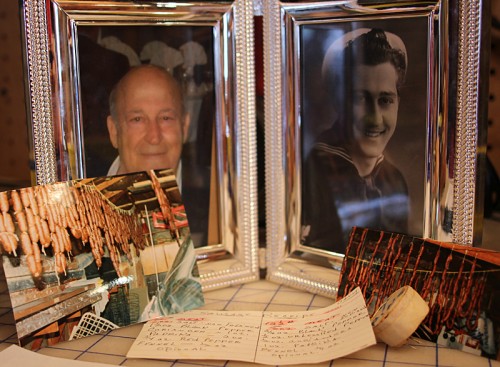

Dante D’Apice and his recipe card

Dante had been a seaman, working a landing craft on D-Day. Back home, he was a house painter; he never worked in a restaurant (though the Schrementi side of Dan’s family has a long-running Italian restaurant in south suburban Steger). “He’d make sausage, he’d make sauce out of anything—sauce out of crab legs, sauce out of snails, in the old days I think they made sauce out of sparrows. It wasn’t a foodie thing—it was the Depression and it was what you did to have food.”

“He’d make sauce out of anything—sauce out of crab legs, sauce out of snails, in the old days I think they made sauce out of sparrows.”

Dante never made a big party out of making sausage, but he’d do it with the whole family, a dozen or so working on making the sausage and cooking afterwards. “We always liked that, it was something that was always around in our family, and when I was old enough to make it, I learned to make it with him,” Dan says. “Later in life as I got married, Megan and I would make it at my house, and then my friends would ask for it, when was I going to make it?”

Dan Schrementi welcomes guests—more likely relatives—to the 8th Sausage Fest.

“But it was a lot of work,” he says. “We were hand-grinding it. It must have been eight, nine years ago that my buddies wanted some, but I was tired of buying it, tired of doing all the work for them, so I said, just come over on the day that I make it. Maybe six guys showed up, and we did everything by hand, pork butts, cutting, trimming, all that. Then every year, we would come up with ideas—like, I’m going to get an electric grinder. Or I’m going to add more butcher stations.” The biggest acquisition came after last year—the first seven years of Schrementi’s Sausage Fest, as it came to be known, were held in his garage in suburban Lombard, but when he and Megan decided to move back to the city, a top priority was a garage and yard big enough to continue the tradition (and hang the sausage afterwards).

Records of how Sausage Fest has grown—from 251 pounds in 2012 to 1,267 this year.

The records going back to the early years are taped to the fridge in the garage and show the event’s steady growth—a dozen friends and 133 pounds around 2010 would become 800 pounds by 2015 and the nearly 1300 pounds of ground pork that three neatly spaced rows of friends had pre-purchased and would be making sausage out of that day. Along the way one of the things to go would be the cutting and grinding—now he buys the pork already ground from Schmeisser’s, an old German butcher on Milwaukee Avenue in Niles.

“Logistically, it’s getting to be a problem. 1300 pounds of pork—just fitting it in my car is getting to be an issue,” he says. “Kurt Schmeisser, the guy who owns it—he gets it. I told him the story, and as I got him more involved, he was so happy to be part of the tradition. The day we made it, he took me in the back, let me oversee the grinding and the seasoning. When I picked it up, he said he used to make sausage with his dad—he was born in the butcher shop, he said.”

“The one rule I’ve had at this is that I don’t let people change the recipe,” he says. “It was my grandfather’s recipe; that’s the recipe. Because the first year, a few people said, I’m gonna bring garlic, I’m gonna bring this or that… no. The only thing you can change is level of heat, because some people like it hotter. I figure that’s fair, you go to a grocery store, you’ve got hot or mild.”

Step 1: Meat is weighed to give everyone what they ordered.

Step 2: The first rule of Sausage Club is that the only adjustment to the recipe you may make, is the level of chili pepper heat. You want to add garlic, orange zest, chipotle truffle? Getouttahere.

Step 3: Three stuffing stations, lined up on a foldaway table built into the wall.

“It’s pretty spicy as it stands. It’s got a lot of black pepper,” Dan says. “Which gives you, not a kind of blow your face off hot, but a kick for sure. And it’s got a lot of coriander in it, which is the other thing that’s probably unique to the recipe. It’s different, and that’s why I think people like it.”

“Does it have fennel?” I ask, licorice-y fennel seed being a hallmark of Chicago Italian sausage versus many other styles.

“There’s whole seed fennel in it. That’s a Chicago thing,” Dan says. “I’d like more fennel in it, but the baseline recipe doesn’t have a ton of fennel in it,” he shrugs, helpless to alter a recipe with such history.

“Last year was the first year I made it that my grandfather said it was perfect,” Dan says. “He was picky about it, even though he was happy we were doing it. He said it was perfect, and he passed away in May.”

“His work was done,” I suggest.

“Right,” Dan says. “His work was done.”

I SNAP SOME SHOTS OF SAUSAGE-STUFFING, but it’s crowded in the garage, between all the guys and all the pork, and I wind up hanging out with one of my sons in the backyard, in the crosswind of a fire pit, the grills being fired up, and a few guys smoking cigars (at 11 am). A steady stream of new arrivals comes up the driveway, often the husband dragging a cooler while his wife carries a baby in a car seat. The women go straight inside, the men head for the garage, often plopping a bottle of bourbon on a table or passing around whatever new brew they arrived with. There are about 40 people out here at the high point, but with a constant stream working the three sausage stuffers, and people regularly packing up their coolers with the sausage they’ve just made to take it home, I can believe it’ll pass the 100 guests Dan anticipates by the time the evening is over.

It’s interesting to me that while the inspiration for this is the kind of things tightly-knit neighborhoods once did in Chicago, in reality this party is the complete opposite. It’s made a circuit from Chicago Heights to west suburban Lombard to the city’s northwest side, picking up a mix of attendees every step of the way—a fraternity brother of Dave’s from Illinois State tends the grills, family from Chicago Heights mingle with new Edison Park neighbors. And there’s a whole contingent from Bourbonnais, where Megan’s family farms—her mom filled her cooler with eggs, and I buy a carton from her before I go. This is the Chicago get-together as it happens today—not a gathering of one neighborhood’s clan, but an event that draws from a diversity of neighborhoods, employers, and even people met on the internet, like me.

By 12:30 I’m hungry and haunting the guy manning the grills. On the pretext of capturing a picture first thing, I manage to snag one of the first sausages to come off, to be served with the grill man’s homemade Italian beef and onion spread.

The first batch is ready, about 12:30.

Homemade Italian beef results in a home-smoked combo

It’s good! It’s a classic Italian sausage, just different enough—I’m not sure if I taste the coriander but the emphasis on black pepper is obvious. It has the taste of an old-fashioned recipe, when people didn’t season things as aggressively as we do now, because they counted on the meat to have its own flavor.

“It’s become an institution in my family that the sausage is always around,” Dan had said to me. “And I just think it’s cool that so many people will have the same experience, they take it and they give it away and have the same recipe that we have. It makes me happy that people like it. Otherwise they wouldn’t keep showing up. I said to Megan one year, it increases by hundreds of pounds every year—I don’t know why these people do this. But there’s something takeaway about it, that makes you want to be involved.”

“It’s not just drinking at 11 in the morning?”

“There’s that, too,” he admitted. “For my grandparents, it was strictly about the tradition of making sausage. They were never having huge parties along with it, so that twist to it is new. Here it’s a mix of making the same recipe, but adding this whole layer of craziness—I’ve got friends coming to it from college, from home, from work, from all walks of life, and they all show up because of this one thing. How many times in life do you get that?”

courtesy Dan Schrementi

courtesy Dan Schrementi

Michael Gebert suggests that you don’t ask how the sausage gets made as editor of Fooditor.

Special thanks to Megan Schrementi, Elliot Papineau.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.

Norwood Park is another neighborhood in Chicago like Edison Park and Jefferson Park. Niles is definitely a suburb and Park Ridge is another adjacent ‘burb to Edison Park (lots of Parks there to muddy the waters).

[…] Alan is a retired Com Ed lineman, and he already owned a farm where he grows ornamental trees—”If you ever want a workout, come dig trees,” he says. Rebecca is a part-time nurse as well as a Master Gardener—a designation given by the state of Illinois to skilled gardeners who volunteer to educate others. She too saw a blank slate for their retirement years where they could grow what they liked and let their city grandchildren run free outdoors. (Fooditor readers have already met one side of their family—their daughter Maggie and her husband Dan host this annual sausage party.) […]