1. HE’S BACK!

Jean Banchet, that is, not literally (he died in 2013), but the Jean Banchet Awards (with which I have a certain involvement—here’s the In Memoriam from the last awards) will return on January 28. The Banchet Awards are easily the most highly-regarded food and beverage awards in Chicago and an important identifier of up and coming local talent, which often leads to them getting notice in national media and at the James Beard awards. They were founded in 2002 by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation as part of their Grand Chefs Gala, an important fundraiser for the foundation as it fights a serious disease often affecting young people, and was spun off as its own, industry-focused event in 2016; the first post-pandemic awards were held in May of 2022. Now they’re being put on (by longtime producer/host Michael Muser) in partnership with Chicago Chefs Cook, the organization that has put on benefits supporting relief efforts in Ukraine, Ethiopia and most recently, Maui, and whose events have included the recent 80th birthday party for Ina Pinkney. Nominees will be announced in November.

Some good followup coverage at Bob Benenson’s Local Food Forum.

Here’s what I wrote following a 2022 piece on them at Eater.

2. SLAVA UKRAINA

If you feel like post-pandemic dining seems to be a lot of steak, pizza and other safe things, there are certain restaurants that feel like a bold, innovative future rooted in underappreciated cuisines. Thattu is one, so is Boonie’s, and now here comes another—Beverly Kim and Johnny Clark’s Ukrainian popup, Anelya, which I went to last winter (read here), will become the permanent replacement in the former Wherewithall space. Anthony Todd in Dish:

Clark was familiar with many Ukrainian dishes through his grandmother, who left the country after the Second World War, but when he recently visited Ukraine, he was surprised to see the depth and variety of the cuisine, as well as the focus on local ingredients. “Unless you’ve been to Kyiv in the past five years, you wouldn’t know that it has a really amazing food scene, even in the midst of a war,” explains Clark. “It’s comparable to Italian food — produce is really important, freshness is important.”

3. AUSTIN POWER

Louisa Chu goes for an eating tour of the Austin neighborhood with the manager of the Austin Town Hall Market, Veah Larde:

To get a sense of what Austin is really like, where does Varde [sic] suggest we go?

“Community gardens,” she said without hesitation. “I love what BUILD has done.” Broader Urban Involvement & Leadership Development is a West Side-based organization focused on gang intervention, violence prevention and youth development. It was founded in 1969, and its new home opened in February. The expansive block-size campus includes an acre of gardens with fruit trees, a three-season outdoor education center and free-range chickens.

4. COLD FISSION

Steve Dolinsky talks sushi in Chinatown (or “East Pilsen”) at 312 Fish Market:

312 Fish Market is a cozy sushi counter tucked away on the second floor of the sprawling 88 Marketplace, which houses a number of restaurants and food shops, just west of Chinatown. Walk past the groceries and just to the right of the no frills dining court to see the chefs unpack enormous hamachi and kanpachi. There’s bright orange kinmedai nestled next to horse mackerel and smaller flying fish.

“We get them from Toyosu Market in Japan twice a week. We also get some fish from Hawaii, also get it from the Atlantic,” said Joe Fung, the Sushi Chef at 312 Fish Market.

5. EMMY ESME

David Hammond talks to the newest artist to be featured at Esme, Emmy Star Brown:

How do you feel your art works with the environment and food at Esmé?

It’s a perfect fit. When I first met with Jenner and Katrina, we were talking about ideas for the space. We found that we all had this common connection with Alexander Calder. I had dreamed of working in three-dimensions for years and years, but I had never pushed myself into that direction. And Jenner had said, “What if we fill the space with mobiles,” and having that kind of support pushed me from 2D to 3D. I’d never worked in three dimensions before, so creating art for Esmé was certainly very special to me.

I absolutely loved that we pulled this off. You know, the first course of the dinner is served on mobiles floating above the dining tables. There’s a pulley system, so the mobiles can be pulled down to the table level and then pulled back up. But then it stays within the space, and that’s really important for me. I want people to see how the art works functionally with the food.

6. THE ROAD TO HECK

Best Intentions in Logan Square has reopened after three years, and Titus Ruscitti checked it out:

More than three years after the pandemic shut down one of my favorite neighborhood bars it’s back and better than ever. Best Intentions quietly reopened at the end of April and had a line of people outside when they made their triumphant return along Armitage Avenue in Logan Square. Best Intentions is what many would describe as a hipster bar and they would not be wrong but it’s still an awesome spot. I don’t think being hipster makes a bar bad but lots of places definitely overdo it. What I like about Best Intentions is how they managed to keep most of the dive bar feel from the tavern it replaced. It doesn’t feel new and it isn’t some over-exaggerated replica of a bar from a bygone era. It’s got the feel of a slightly updated dive bar and most of the updates come in the form of the food and drink menus.

By the way, last week I quoted Titus saying that the management of Webster’s Wine Bar also runs Rootstock. Friend of Fooditor Scott Worsham wrote to point out that they have not been connected for a couple of years.

7. COMBI AND POKÉ

Michael Nagrant ate white boy tacos (but no poké; that’s just a headline joke) at Tacombi, a chain now in the West Loop. Here’s what he thought:

There is authenticity at Tacombi. The birria is shredded velvet and the accompanying consommé works as a killer chili-spiked chaser once the taco has disappeared.

…The tortillas at Tacombi are pliant and full of corn perfume, not as good as say the fresh comal-griddled beauties from Rubi’s on 18th or the ones from Taqueria Chingon, but better than a lot of the ubiquitous dry ones often slung by local tortillerias.

He also made a recording of this one, so you can listen to it while making tacos.

8. RUNNY FOR BREAKFAST

Maggie Hennessy gets results—she writes about a runny-yolk breakfast sandwich at Loaf Lounge and guess who went out and had the very one a day or two later?

It’s a decadent little thing, set on a checkerboard-print paper in a plastic basket. I like cradling it with both hands even though it only requires one; the first bite releases a golden river of yolk, through which I drag every subsequent bite. The muffin’s irregular structure stretches like a mini trampoline to keep the fillings intact. Its griddled edges lend just enough crunch.

9. PEOPLE WRITE BOOKS

Mike Sula looks at seven Chicago food books coming this fall season, one of them talked more about below in this newsletter, and three of them from the publisher of my eventually-upcoming book, Evanston-based Agate. This one sounds interesting (not that the rest don’t) and fitting for the times (again, not that others aren’t):

The Sacred Life of Bread: Uncovering the Mystery of an Ordinary Loaf, Meghan Murphy-Gill (Broadleaf Books)

Small enough to fit in an apron pocket, this collection of essays and meditations—sermons, even—from a former journalist and practicing Episcopal priest is a map toward developing a “spirituality of bread.” Released in early June, each chapter examines some aspect of bread or baking as a metaphor for inner truth, and ends with an appropriate recipe. “If you have no spiritual practices in your life or are looking for a new spiritually edifying habit to maintain,” one chapter begins, “may I suggest a sourdough starter?”

10. BAGEL HISTORY

The Bagel owner Danny Wolf, a Holocaust survivor, died at 77 last year. Now a 78-year-old has taken it over: entrepreneur Marvin Barsky:

In 2021, Barsky bought Stella’s Diner, The Bagel’s cross-street Greek rival. It was a means to curb the then-retiree’s restlessness — and he was certain this venture was his last. Then Barsky befriended Wolf, the man behind his perennial cravings: Reubens and bagels.

The two rubbed shoulders instantly. With over 150 years of lived experience between them, it was hard not to, Barsky said. Competition softened into friendship, and the septuagenarians evolved into North Broadway allies and occasional lunch buddies.

11. PREVIEWS OF COMING ATTRACTIONS

One thing I’m always eager to check out at Eater is a roundup of opening-soon restaurants—hopefully it includes some interesting places, and this one certainly does; I can’t wait for a new John Manion restaurant, Ramenlord Mike Satinover’s permanent restaurant, and the Ramova Theater complex.

12. A TRADITION ENDS

Sorry to hear that one of the traditions at LTHForum, the annual picnic where members brought whatever oddball thing they cooked up to share with friends from the almost 20-year-old culinary chat site, was canceled this year. Apparently the powers that be decided that not enough people had signed up to make it worth it, which seems odd to me as there were about 30 people signed up—down considerably from high points in the late 2000s/early 2010s, I suppose, but to me the old LTH spirit was that if two people showed up, that was two old or new friends to have a fun time and eat good things with. Perhaps the powers that be did not see that the people they wanted to see had signed up—that would not surprise me, as the event (like most of LTH) had taken a distinct “in-crowd/out-crowd” tone the last time I went, in the early 2010s, and many of the in-crowd fled at the site of me approaching, food in hand and apparently, trailing brimstone smoke.

The site will enjoy its 20th anniversary next May—assuming it exists by then—but the dispirited nature of this announcement suggests that there’s little hope for a revitalization; the site has been somewhat unwelcoming to both new posters, and a lot of the more notable older ones, for quite some time, as people moved on to other, less restrictive forms of social media. If you ask me, the interest and creativity that originally founded LTHForum is still alive, at NewCity where David Hammond writes, at Titus Ruscitti’s blog, at Greater Midwest Foodways presentations arranged by Cathy Lambrecht, on social media when Kenny Zuckerberg comes to town and finds Italian food no one else has paid attention to—much more than at LTHForum in recent years. And it just kind of floors me that a site which still has some activity, and could probably have a lot more with very modest efforts at outreach, sees no way forward—compared to 20 years ago when it was created from nothing and nobody, and changed food culture in Chicago.

13. LISTEN UP

* * *

BOOK REPORT

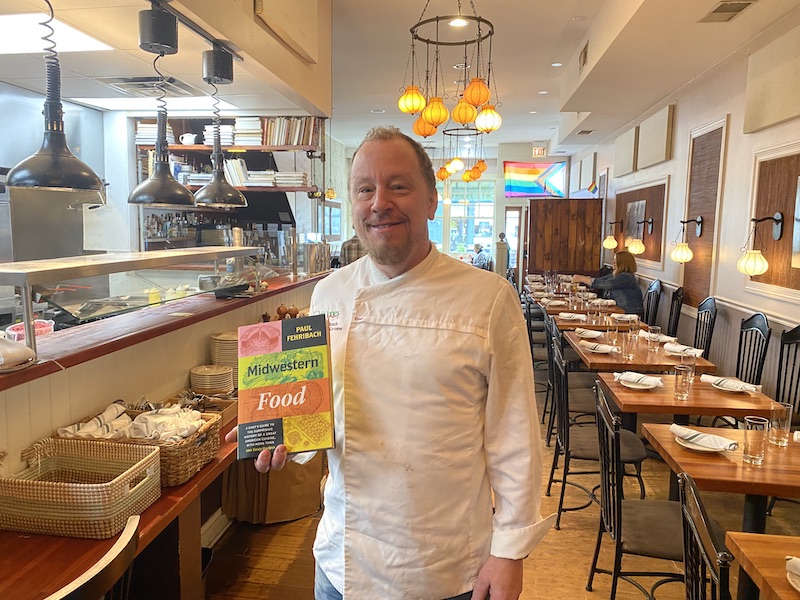

The book

Chef Paul Fehribach is known for having a Southern restaurant, Big Jones. But the truth is he grew up near the border—Jasper, Indiana, near Evansville, officially in the midwest but located across the Ohio river from Kentucky—and thus a place where Southern and Midwestern food cultures wind around each other like the two banks of the twisting river. Of course, one of these cultures is much more commercially appealing than the other—Southern food culture has lots of cachet, Midwestern food culture is a bit of a joke, made of Jell-O salads and casseroles. Fehribach’s new book, Midwestern Food: A Chef’s Guide to the Surprising History of a Great America Cuisine, With More Than 100 Tasty Recipes, coming out September 20 from University of Chicago Press, sets out to reclaim the food heritage of a region that grows much of the nation’s food and includes a wide array of cultures—and continues to evolve with immigration (this is surely the first book to include a recipe for homemade Jibaritos). If nothing else, he hopes to encourage you to pickle and bake like Grandma did. I spoke to Fehribach at Big Jones:

FOODITOR: First, let’s dig into the cliches about the Midwest versus what you’re trying to express that it really is.

PAUL FEHRIBACH: As with a lot of cliches, there’s a grain of truth to them. The meat and potatoes, the ranch dressing, the bland casseroles. But it’s a very diverse regional cuisine, and as we find out in the book, there’s a lot going on everywhere.

The grain of truth to those things is that the cuisine evolved. Along with industrialization, the Midwest was later to settle than the south and the east coast. And so you have immigrants coming over, primarily from from Central Europe at the time, Germany and later Poland, Dutch people, later Scandinavian, and settling in the cities. And this is when factory jobs were what you had. So you’re busy, a lot of times two people working. And you have industrial food happening at the same time, they’re putting food into cans, they’re getting really efficient at freezing vegetables, and all of that. And so it’s very natural that all of this rapid change for these immigrant groups results in things like [the Minnesota specialty] hot dish where a really busy family can open a can, open a box out of the freezer, boil some pasta, brown some ground beef, put it all in a casserole and put it in the oven and forget about it for an hour. And then you’ve got dinner.

Those were the sorts of things that we did because we were busy and, you know, we’re Midwesterners. I think that it might be that German and Scandinavian blood, nose to the grindstone, just getting shit done. Where New Yorkers and the East Coast like to talk about themselves a lot.

Yeah, no, I think there’s definitely kind of in the Midwestern personality, a don’t talk yourself up too high mentality. So what about midwestern food should people rediscover?

I’d like people to rediscover a geographically diverse Midwest that has a lot of diversity in its cuisine. I think again, because of the industrialization period, we find ground beef is important in every corner of the Midwest. But what’s done with it varies, if it’s something like Cincinnati chili or or Detroit’s Coneys, for instance, and all of the sausages that we have. And depending on where you go—you know, in Minnesota butcher shops do different things than they do in Cincinnati or St. Louis. Because you have a large population of people from Scandinavia, you also have a population of people from Germany up there, but that tends to be more from the Protestant north of Germany.

So you get things like mettwurst, as opposed to bratwurst. You see things like gritzelwurst, which I think Titus Ruscitti was posting about the other day, he was in Minnesota, and it’s sort of like goetta [a Cincinatti specialty of meat and oatmeal], basically the northern German version of [Louisiana] boudin. You find things like zwieback in Kansas, influenced by the Mennonites, and the bierocks out there as well. One thing that actually didn’t make it into the book, because the fried chicken chapter just got so long, is that I didn’t even discuss Barberton, Ohio and Barberton chicken [a specialty of one town near Akron]. So it’s a very diverse and dynamic regional cuisine.

Mentioning fried chicken brings up a good point. We all take it for granted that it’s southern, but it’s everywhere in the midwest—I grew up in Kansas, and there are no famous restaurants in Kansas, but the few that do exist, like the Brookville Hotel or Stroud’s in Kansas City, are all fried chicken places. And you make a compelling case for fried chicken really coming from Germany.

Fried chicken was another Catholic thing. I couldn’t find it in any of the cookbooks from the north of Germany, from low Germany. I grew up in this town, Jasper, and it’s a really closed, insular place. It’s never been welcoming to outsiders. Everybody in that town is from the same two towns in Baden. And yet we all grew up eating fried chicken, and so everything we’d heard about sort of the established narrative of fried chicken [originating in the South] in America never really made sense to me.

I thought, well, you know, maybe I’ll just figure out how to read some of these old German texts, figure out how to acquire them first, and it turns out that the Library of Congress is actually a really good resource, a lot of the books are literally online. The hardest part was learning what they called chickens. Because in German there’s at least a dozen different names for chicken depending on where and when you were. But so wherever the Germans went, is where you find fried chicken, and you don’t really find fried chicken anywhere in the United States before you find German people.

The interesting thing to me about Barberton chicken is that they put this kind of sweet and sour—relish? Dressing? Whatever you’d call it—on the chicken. And it struck me as being very like Jewish cooking. So is German cooking more Jewish than we know, or is Jewish cooking more German?

I think it resembles Amish cooking to a large extent too, the seven sweets and sours that they put on the table, but that’s actually a really good point. And I always thought that the fried chicken part of it at least, you know, Serbia [the ancestry of many of the Barberton chicken restaurants], that’s the old Austro-Hungarian empire. And you know, we have fried chicken going back at least to the 13th century in Vienna.

Well, let’s talk relishes for a minute. You start the book with a chapter urging people to get back to making their own relishes, which is the answer to “it’s all bland food”—well, it isn’t if you put a relish with some kick on it. And it’s a natural thing in a farming part of the world, to divert some of the growing season into things preserved with salt or vinegar.

That’s a really good point about the cuisine. When we started here at Big Jones, well, you cook Cajun food, and everybody comes in thinking that it’s going to be really spicy and punchy. And that’s what hot sauce is for. You go into a cafe in rural Louisiana, and get gumbo, it’s not spicy. You have your relishes, and you cook on the less-seasoned side, it gives everyone an opportunity to finish their own plate.

So what relishes do you think people should make?

People should make chili sauce—

Which is what?

It’s basically ketchup, but it has a little more of a spice profile to it. It might taste somewhere between ketchup and barbecue sauce. I think the only thing I ever knew it for was in some cocktail sauce recipes. But 100 years ago, it was ubiquitous. You’d see the supermarket advertisements for it, it’d be ketchup, chili sauce, mayonnaise, mustard. You eat it with meat. I mean the flavor profile again, it’s like ketchup, maybe a little bit more vinegary. And it might have horseradish in it but typically is like, a little bit of clove, a little bit of allspice maybe, maybe not some cinnamon, but definitely some ginger. So it’s just a little more interesting but even just for French fries, it’s more interesting than ketchup. I love ketchup but you know, change it up sometimes.

People need to be making piccalilli, they need to be making chow chow. Those are the big ones, I would say. Our whole pickling and preserving culture sort of devolved into just cucumbers on the shelf at the grocery store.

Another thing that you talk about, and this certainly matches up with how I grew up, is how much people in the midwest bake. My mother-in-law was not a great cook, but she had one coffee cake that was very good, out of a Junior League cookbook of course, and my wife makes it too. So tell me about baking culture in the midwest.

I think the midwest is easily the most fascinating and delicious baking region in the country. And it comes from that foundation of of both German and Scandinavian traditions, even from the Hungarian things and Serbian things that you can find in Ohio, and particularly Cleveland. But the Germans left the strong coffee cake traditions and St. Louis, you can go to the Missouri Baking Company and still find stuff that looks like it’s 1890 and all made by hand. Really, really good stuff. And then, you know, the kringles in Racine, and things like a Mexican wedding cookie—when it shows up in the southeast, it’s called Russian Tea Cake, because that’s what Betty Crocker calls it in “big blue” [cookbook].

There’s strong evidence, I might delve into this at some point, that the midwest was influencing southern baking culture, certainly more than southern baking culture was influencing the midwest. The south’s prodigious talent with cakes, it really begins with the Iglehart brothers in Evansville, Indiana with Swans Down cake flour. Because really cakes didn’t become a thing until you had baking powder and stoves with reliable heat. The midwest was already sending flour all over the country at that point.

No mention of pfeffernüsse? In my mom’s family that is the old family Christmas tradition, and everybody has their own way of making it—with milk, without…

I’m constantly becoming aware of things that I was cognizant of, that I was leaving out. When we got over the 90,000 words that I was contracted for, they didn’t really get push back, but once we got to 120 they’re like, Stop. So that’s why pfeffernüsse didn’t get in there. It’s why roast beef commercial [a Minnesota hot sandwich] didn’t get in there. I have a list of things that are likely if I do another, bigger book.

I think your fate is going to be people like me saying “I can’t believe you left out…”

I’m kind of looking forward to that. Maybe eventually I’ll start dreading it. I think the publisher was worried about having a package that was affordable for people. And sure, that’s good guidance from them. Because I’m a nerd, I would have made it 400 pages and cost 50 bucks, and we’d sell 500 copies.

One thing you do have is Amish Friendship Bread, which you include while admitting that it’s basically “fakelore,” that is, something that sounds like folklore or an old traditional recipe, but actually is a fairly recent invention, or for tourists, or whatever.

Back home [in Indiana] you see that all of the Amish restaurants are serving fried chicken. But Amish people don’t eat fried chicken. You see this in Pennsylvania also, where these restaurants that sort of started popping up in the 1900s would serve fried catfish for the the tourists coming up from New York, and they were selling what the city folk perceived as country cooking.

So Friendship Bread [a sweet sourdough loaf that comes with mythology about passing along the starter as a gift] has nothing to do with Amish culture, with daily life. It’s actually a fairly recent thing—I couldn’t find evidence of it before the mid-80s. So people just call something Amish when they want to pass it off as legitimately country. I don’t know how the Amish feel about that, but I imagine if they can make good money selling fried chicken to the plebes…

To the English, yeah. I like that you talk about how Mexican and Asian influences are going to be the next thing in midwestern food culture. I mean, they already kind of are in a world where salsa is our number two condiment.

Yeah, I had a long debate about whether to include salsa recipes or discussion about salsa in the book, and it’s like, it doesn’t really meet my arbitrary three-generation threshold. But yeah, I think those are going to be the next ones. I think African cuisine would be interesting. Obviously here in Chicago, you see a lot of Somali, Minnesota, you see a lot of Somali stuff coming up. If you go to Dearborn [Michigan], I ate at the Iraqi Kabob House and yeah, damn. But the danger is of course, that those things will live and die within their immigrant communities. I think Mexicans and Asians, they get out and work in the restaurants, so maybe they’re more successful realizing their cuisines into the mainstream.

Let’s talk side dishes. You have a great line about “the french fries and austere side salads that cast a monotone over all our nation’s cooking.” I was thinking about that when I read about Beverly Kim and Johnny Clark opening their Ukrainian restaurant, we think of side dishes in Eastern European food as being stuff out of jars, but they’re really like any farming culture—they’re making meals out of the fresh stuff they grow. Italy gets all the credit for cooking like that, but they’re all doing it, or at least they were until industrialization reached them.

If you look in the old community cookbooks, we talked about how much midwesterners bake, and the pride they take in that. But those cookbooks also had a ton of vegetable recipes, until you get to the 1960s when it starts to dwindle. Even just with potatoes, there’s so many more things you can do with potatoes, but you know, there’s vegetables like rutabagas, roots, turnips, beets, all of these things. We start to lose a lot of our identity when we don’t have these things—like in my hometown, every restaurant has German fries, and you just don’t see them anywhere else. And they’re basically a certain treatment of home fries. But you see them in Dubois county, a little bit in Daviess County. And it’s a major touchstone of identity there. I mean, people talk about restaurant versus restaurant based on their German fries, it’s a major point in discussing the virtues of different restaurants.

Part of what I want people to take away from this book, is what Titus Ruscitti says—to eat like the locals eat. Find what’s unique in the place that you are. Go the couple of extra miles to to find that locally owned a cafe or that locally owned tavern that’s been there forever. Or you can find the chef-owned places that are trying to do the farm to table thing and put up a new spin on midwestern cuisine. But definitely patronize your local businesses and try to find out what’s unique where you are, rather than just giving up and hitting the Panera Bread right on the interchange. I can assure you there’s a much much better sandwich if you go just another mile or two.

As I studied Southern cuisine, and would go to these cities in the south for different events, I’d often wind up in a small town, looking for a good place to eat. And I started sort of envying this about the South, that it seemed like every town had like this cool little old cafe that had been doing the same thing for 60 years. That definitely had local flavor and a real local identity to whatever town it was in.

And then I started coming home, as my parents started getting older, and I was like, we actually have all these same things, I just took all of this stuff for granted. When I was growing up, I never thought Snaps Cafe was special or worthy of note, I never thought The Chicken Place in Ireland, there was anything remarkable about it. And when I started traveling back there, I’m like, holy shit. And so I wanted to start documenting that stuff. What I really wanted to do was dispel a lot of the myths about, say, sugar cream pie. Or fried chicken for that matter. I wanted to start a serious conversation about Midwestern cuisine. Establish it as a legitimate and beautiful regional cuisine as much as Southern cuisine, and California cuisine, and Mexican cuisine and Chinese cuisine.