NAOMI DUGUID’S TASTE OF PERSIA WAS one of the best reviewed cookbooks of last year (winning the International Association of Culinary Professional’s prize for best Culinary Travel cookbook), partly because of its eye-opening look at the cuisine of the region that includes Iran and the Caucasus. But also because it’s a beguiling adventure tale of one woman alone, making her way through countries, some of which are kind of on the far side of the globe from us, politically speaking. In the book she professes little concern about her travels in such places—though she acknowledges that a few places she went have since fallen prey to ISIS.

The book

Duguid, a Toronto native perhaps best known for Hot Sour Salty Sweet, a seminal book on Southeast Asian food written with her ex-husband Jeffrey Alford, will be in Chicago this week for BESPOKE, a culinary conference run alongside the Grand Cochon competition this weekend. She has two public events while she’s here: on Friday night, she’ll be at a dinner with a $45 set menu of dishes (also available a la carte) from her book prepared by Edgewater restaurant Income Tax. There will be Persian-influenced wines as a pairing, and copies of her book (at a 20% discount) available for signing. To reserve a space, call Income Tax at 773-897-9165.

On Saturday, she’ll be the keynote speaker at BESPOKE’s symposium, beginning at 10 am at the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel. At lunchtime, there will be a Persian-themed tea break with vegetarian lunch prepared by Income Tax, at which attendees will rotate through tables including the featured speakers, for a more intimate experience. To get a ticket for the symposium and other Grand Cochon and BESPOKE events, go here.

In the meantime, I spoke with Duguid about her book and her remarkable travels, to get a better sense of why she argues that Persian food is a broader subject than just Iran, with more influences than we realize in our cuisine.

FOODITOR: Your book is called Taste of Persia, and most assume Persia equals Iran, but the subtitle, A Cook’s Travels Through Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, and Kurdistan shows that you really see it in terms of an empire covering an area that stretches up against the other empires of the region—Russia with Azerbaijan and Georgia, Turkey with Kurdistan and Armenia. What’s your vision of this region as reflecting one unified cuisine?

NAOMI DUGUID: When I was first talking to my editor, she said, “So it’s Middle Eastern?” And you don’t want to describe something with a negative, but it’s not Middle Eastern, it’s not Turkish, it’s Persian and it’s Persian-influenced. And if you go way back, way back before there was Russia, it was basically the Persians and the Byzantines—who were Greeks, really, who controlled what we now think of as Turkey—who argued over who was going to control that huge landmass in the Caucasus. It’s way older than any idea that these countries were any part of the USSR.

So people go to Georgia and they go, wow, the food is so incredible—but they have no idea that it has connections to ancient Persia. And so it’s that kind of thing—in our views of these countries, we get distracted by the news, ranting Ayatollahs or raving Putin or whoever. But there’s human beings in the kitchens, and they have grandmothers and great-grandmothers. There’s a landscape that produces pomegranates in Iran and pomegranates in Azerbaijan.

Laura Berman

Laura Berman Naomi Duguid

As we know, national borders are not at all a good reflection of culinary borders. It’s very fluid. And I wanted to pull that together. I wanted to talk about the coherence of it, instead of what often seems to be incoherence. I said to my editor, it’s not so confusing if we can have a map. I went for three maps, and I got two.

The point is, you can have a dish from Iran and a dish from Georgia and a dish from Azerbaijan, they’re not going to argue with one another. It’s like eating around the Mediterranean, there’s a palate—there’s ingredients that talk to each other happily. And that’s really fun, and suddenly it starts to make sense. I had an idea of this, but the more time I spent in the region, the more I saw it.

For Persian food, we tend in this country to think of a big pile of rice with kabobs on top of it, but of course like any peasant cuisine, it’s not a cuisine built around eating tons of meat—and your book is full of these beautiful pictures of vegetables and the fresh, slightly tart green salads we associate with the region.

It’s layers of green flavor, is how I think of it. Some of them cooked, like all those ashes, the Kurdish soups, and some of them fresh herbs. It’s sustainable and local—okay, before the Columbian conquest they didn’t have tomatoes, but otherwise everything is local and they’ve been sustaining themselves and not starving for over 2000 years.

So it’s not a bad model [nutritionally] and people seem to thrive on it. And we think about wine originating there, and all the sorts of fruits that we grow in the states basically grow there. The climate’s not exactly the same, but it’s quite a familiar palate in terms of the shopping basket.

And you talk up front in the book about the basic pantry, and it’s really nothing we don’t know—it’s mint, it’s saffron.

Yeah, absolutely. There’s the blue fenugreek from Georgia, which is a little unusual, but you can get by, you cope in the same way immigrants have always coped. But the basic ingredients are all here.

Which you say is partly because there was a lot of Persian influence in European cuisine in the medieval era.

It’s such a long time—we think in terms of decades, and to say, “Well, two thousand years ago—” that sounds a little pretentious. But if you think about the Arab conquest of Europe, it’s like the Mongol conquest of China, a nomadic group conquered China, and they took on Chinese civilization. In the same way, the Arabs conquered Persia and they took on Persian culture and technology. So when they crossed northern Africa into Morocco and Spain, what they took with them wasn’t nomadic desert cuisine, it was Persian culture adapted to different places. Like tart fruits mixed with meat in Moroccan food.

When I looked into peoples’ store cupboards it would be like, this is where Aladdin’s treasure cave, “open sesame,” comes from.

And then when you think about the Crusades—all those armies from Europe who went marching to Palestine, the leaders of that, the knights, they brought back a taste for things that goes back to Persia. The use of quinces, or like a mint sauce on lamb, I swear that goes back to then. Diluted, nothing’s ever a pure influence, that’s the whole interesting thing around food, but there are strains of influence, so it’s not wildly unfamiliar anywhere. Like the yogurt, and fresh cheese, that you see in northern Europe and eastern Europe.

Obviously there’s dried fruit and things like preserved lemons, but how big a role does preserving play in Persian food?

When I looked in Georgia, and Armenia, and Azerbaijan, into peoples’ store cupboards, their larders, it would be like, this is where Aladdin’s treasure cave, “open sesame,” comes from. There would be rows and rows of jars—there’s one picture from a Yazidi household in Armenia of jars under bedding. And they glow, these peaches in jars. So people are putting these up, but also the fruit leathers and other things that don’t require a glass jar, they just use the heat of the sun.

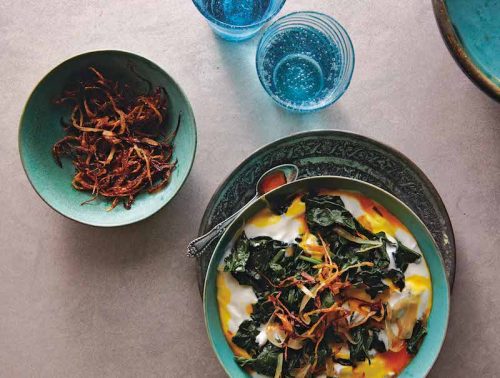

Excerpted from Taste of Persia by Naomi Duguid (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2016. Photographs by Gentl & Hyers.

Excerpted from Taste of Persia by Naomi Duguid (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2016. Photographs by Gentl & Hyers. Spinach Borani

There are dried greens, dried beans, dried herbs, some preserving of meat, the thing that in Turkey is called basturma. And the Georgian adjikas—they’re so amazing. I have a number of friends who are hooked on adjika, and people hoard it—”Well, I know I made it to give away, but my family’s going through it so quickly I don’t think…” When people are getting turned on to using ingredients that are locally grown, but are being reconfigured because of a culinary culture in the Caucasus—how fun is that?

It seems like the only one of these countries that has large cities is Iran, the rest are not that populous. Is there a notable difference between city and country food in this area?

Cities are a place where wealth concentrates, and there’s more foreign influence. So in Kurdistan I was in Erbil, the capitol—this is before ISIL invaded, of course—and Sulaymaniyah, which is a town with an American university, and I describe in the book the one Italian restaurant. I think the question is, what’s the food in peoples’ homes? Well, I think there’s home cooking in that region and my sense is, home cooking goes on, everywhere, but the bigger the city, perhaps, the less of it there is.

In Tbilisi, in Georgia, now that it’s the post-Soviet time, everybody in the family has to go out to work, the economy is kind of ragged, people are working hard to make ends meet but they’re doing it with grace, the older women who are over 60 are making things from scratch, and they’re cooking for their daughters who have to work. But the layers of work that go into making things from scratch—people don’t have the time to put that in, as they did in the households I saw in rural Iran.

It’s really analogous to, if you were living on a farm in Idaho or something, there’d be more preserving, and things would be paced differently than life in the city.

Where dinner is “What do you want to get delivered tonight?” Now, you talk about one street food, a potato and egg wrap in Iran—did you encounter a lot of street food?

Not in that sense of lots of little stalls with a gazillion things—it’s not like southeast Asia in that way. But you can grab a flatbread any time, and there were these sugar beets cooked—very basic, working man or student food on the run, unglamorous food, you might say. And then there’s sweet treats.

But mostly there are little cafes, so you’re not going home for lunch, you’re going to sit down for a skinny little kebab or two, meat on a stick with a grilled tomato, which might be kidney, say. And in Georgia you go into a hachapuri parlor, and have some kind of an incredible bread and melted cheese thing, with or without an egg on top.

To go back to the guy with the egg and potato thing—you know, that’s pretty minimal. He can make it all at home, he’s just keeping it warm, and then he’s doing a process for you. And why he doesn’t have, say, cheese—well, that would be more money for him, so he’s just sticking to the egg and potato. It’s entry level.

Excerpted from Taste of Persia by Naomi Duguid (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2016. Photographs by Gentl & Hyers.

Excerpted from Taste of Persia by Naomi Duguid (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2016. Photographs by Gentl & Hyers. Eggplant Roll Up

All right. We’ve been talking about the food, but I think the thing that fascinates a lot of people about this book is just that you traveled to these countries that seem kind of scary, Iran, Kurdistan, Azerbaijan—as a woman by herself no less. And you describe several experiences on trains or other places where you had a chance to talk to people, other women in particular, and get some insight into what their lives were like.

I really like not knowing what’s going to happen. That’s my form of adrenaline. And I think for many people, travel is about knowing where you’re going to stay. For me, it’s a little about being vulnerable, and not having a set agenda. Because before I go, I don’t know enough—you can never know enough to get it right. I’d much rather see how it all evolves. And there’s going to be things I get good luck with, and there’s going be things I miss.

So instead of a list I go with a sense of possibility, hoping for the best, and taking enough time so that something good can happen. I tell the story in the book of taking a phone to my contact’s brother in Kurdistan. And I think, I’ll call him when I get there in this collective taxi, and then I’ll find a place to stay and I’ll see what happens with the rest of my time here.

But no, I got scooped up, he came with a friend, the friend had a car, we drove to the home village which was two more hours away, and then that was that! It’s really lucky I didn’t have plans, because what a privilege. It had its complications—I’m happy and comfortable sleeping on the floor, I don’t have an enormous need for privacy. But for me, those encounters, and this question of how much language do you have—well, you can do a lot with gesture and connection and openness. It can be tiring to stay open, it can be tiring to stay tuned in to a language that you’re learning, slowly. But if I’m going to complain about being tired, I might as well stay at home.

I do have to realize that for a lot of people, that’s not what gives them pleasure. And they think, oh my God, you mean you were sleeping in a room with five other people? When did you get any time to yourself? Well, not, except when I went to the washroom. But that’s okay, and yeah, at the end of it it was kind of nice to be home and be in a place where I could close a door, but in the meantime, how fascinating to be an insider for a moment. How lucky.

Michael Gebert is pricing airfares to Georgia as editor of Fooditor.

Cover image: Baqlava from Iran. Excerpted from Taste of Persia by Naomi Duguid (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2016. Photographs by Gentl & Hyers.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.