“WHEN I WAS YOUNG, THAT WAS HOW beef was,” says Rick Whittingham. “It wasn’t pumped full of steroids.”

I’ve asked him how he can tell the difference between the naturally-raised beef that he’s marketing under the brand Chicago 250, and the commodity market beef he also sells that has been subjected to all the industrial magic that modern agriculture has. Turns out, it’s pretty easy if you visit a farmer who’s raising both kinds. “He shows me a couple of cows,” Whittingham says. “They’re the same age, and one looks like Arnold Schwarzenegger…” he laughs, leaving you to imagine the Frankencow he found himself face to face with.

Whittingham is 51, and so he was a kid in a family that ran a butcher shop on the South Side of Chicago through the era when the beef business was revolutionized—incidentally, putting an end to the Chicago stockyards. His father’s father had butchered whole animals, shipped by train to Chicago and slaughtered somewhere in the vast Union Stock Yards starting near Halsted and 41st.

Rick Whittingham and his son Bob

But then came the era of boxed beef, when the big meatpacking conglomerates began slaughtering out on the prairie, in Kansas or Nebraska or Texas, and sending boxes of primals (sections of a steer to be broken down further into individual cuts) or simply boxes of a single cut—four dozen steaks from different animals in a box. The slaughterhouses—he just calls them “houses”—raise the cattle themselves on giant feedlots, and use steroids and antibiotics to produce the most meat on the biggest animals possible.

Now Whittingham works with some farmers who raise cattle both ways a couple of hours to the southwest of Chicago, near Marseilles and Starved Rock. But there’s something he’s noticed about these farmers. “They do grow for the bigger houses, but their families will not eat that,” he says. “They only eat the meat we get,” the naturally-raised meat intended for the Chicago 250 program.

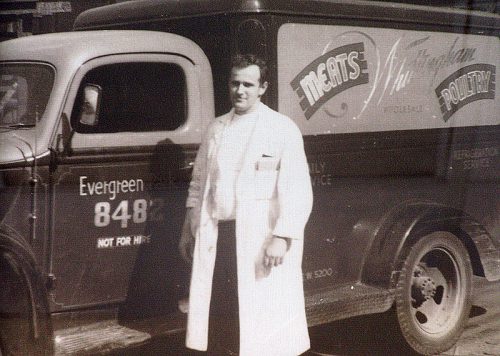

Richard Whittingham Sr., and his first truck, c. 1947

WHITTINGHAM MEATS, IN THE SUBURB OF ALSIP, straight south on Pulaski at 127th Street, claims 70 years in the meat business, but it actually goes back even further than that. “My great grandfather had a grocery store in Chicago back in 1909, but he lost that in the Depression,” Rick says. “My grandfather was a manager at A&P, and he bought a truck off a guy for $100, and he went down to the Yards, picked up some meat, and started peddling it.”

That was 1947. The grandfather, Richard Whittingham Sr., had a wholesale business located at 72nd and Racine—Englewood—but as south side businesses tended to do in the racial unrest of the era, it relocated to the south suburbs in the early 1970s. Rick’s father ran it as a wholesaler and butcher shop open to the public, and then in 1999 Rick bought his father out, and expanded the meat cutting and warehouse side. Under his father, it was about 50-50 between wholesale and the butcher shop; today, although the butcher shop is busy with calls about corned beef for St. Patrick’s Day when I visit, it’s about 80-20 wholesale to retail.

“My dad sold to restaurants, bars, a lot of Greek restaurants,” he says. “When I took it over I started hitting the city—hotels, bars, white tablecloths. A lot of casinos, and we do about 80% of the country clubs in the area. What really helped me out is when the market crashed,” he says.

I wait to find out what sense that makes. “We were kind of a small player at the time, and Allen Brothers was the crème de la crème” of Chicago wholesalers, serving high-end restaurants all over the country, he explains. “But when the market crashed—that’s what helped me get into the country clubs, they all started having to watch their food costs. So that got us into these places for tastings, and when they see that we’re $5 a pound less… But listen, I’m never going to knock Allen Brothers. When they sold the company [to Chefs’ Warehouse], we hired a lot of their people and that’s how we learned to buy meat the right way, the Allen Brothers way.”

Portioned short ribs for a country club event

If you’re a country club chef, you see the same diners week after week. So what you prize is not just quality, but consistency—no chance for a member who’s on your board to start grousing about how your steaks aren’t what they used to be. In Whittingham’s mind, the late Allen Brothers CEO Bobby Hatoff created the model for achieving consistency: “Mr. Hatoff, he only bought from two houses. So when you buy prime, you’re getting the same steak every time.”

Whittingham followed the model, and “that’s when we really got into the clubs and we built relationships with the managers and the chefs. It’s all about relationships, you dial here and you get the girls on the phone. The other guys, it’s all dial 1 for this person, that’s where they’ve gone. They get someone who doesn’t even know about meat, they just take your order.”

The core of consistency is buying beef raised under the same conditions. “It’s all midwestern beef. We only get meat from certain houses, and it has to be a midwest house. Texas and Arizona have feedlots, but it’s 90 degrees out, a steer is just like you or me, if it’s hot out you’re not going to eat,” he says. “The USDA bug from that facility has to be there [stamped on the meat]. If it doesn’t have that bug, we just tell them to leave it on the truck. Now we can focus on walking in with a consistent sample and saying, ‘Give our steak a try.'”

So, given a world in which houses with big feedlots raising pharmaceutically-maximized beef rule the marketplace, Whittingham has found his niche, and makes it work for his customers—and himself. “I own the business, I’m not bringing guys with money in here so I can get bigger and give myself more headaches,” he says.

So why does he want to change the way his business works?

Dry-aging room

15 OR 20 YEARS AGO, BUYING MEAT LOCALLY at your farmers market or directly from a farmer was a niche of a niche. Something only a few restaurants at the high end did, charging a premium price for an often smaller (but hopefully more flavorful and sustainable) piece of meat. Even as distribution has grown with dedicated distributors like Local Foods, many would still think of it that way in a Costco Mega-Pack nation.

But Whittingham Meats is proof that as consumer awareness grows, the meat industry is starting to get it from both sides. Country club members dine at downtown restaurants and see what’s happening there; country clubs hire chefs who come out of a world where being able to say farm to table on a menu is a sign of quality. “A lot of the country club people want the story, the source,” Rick says. “Farm to table is very big now, especially on the north side.”

And it comes from farmers as well. About five years ago, he was approached by a group of farmers in the Marseilles area. “I met a couple guys, and they introduced me to a few more. And I went and saw their farms, and I thought it would be a nice little niche. Everybody wants to know where their stuff’s coming from now,” Whittingham says.

“They do an Angus program. Their animals are born right on the farm, raised on grass, finished on grain, there’s no steroids or stimulants,” he says. “They’re not put in feedlots—so they have a very nice life. We use a slaughterhouse out in Earlville, as well as Aurora Packing.” The proximity to the cattle’s, er, final destination is important: “Our animals don’t travel. In the midwest, you get animals from a feedlot, they have to travel 150, 200 miles to get to a slaughterhouse. For ours it’s maybe a 20 minute ride, so they’re not stressed.”

From the diner’s viewpoint, he says it’s an excellent steak: “You can really tell the difference, when they’re not rushed through the aging process. And if they tried to slip something in, you could tell right away, just by the size of the ribeye.” But it also affects how the farmers live their lives: “They want to see a change. They mass produce for some of the other guys, but they like to see that. And it’s kind of a feelgood story that when this gets put on one of our menus, they’re proud of that. It’s like us, when we see our name on somebody’s menu, we take a lot of pride in that.”

Besides the menus of country clubs, Chicago 250 is turning up on some menus in the city, maybe not as the primary supplier but part of a restaurant’s supply chain—they sell to Tortoise Club, to The Purple Pig, and they supply for the banquet and catering side of GT Prime. The question I wonder about, though, is the company’s own area. Alsip may be close to places that have country clubs like Olympia Fields and Midlothian, but it’s a blue collar suburb, fast food and Greek coffeeshops, and I notice that Chicago 250 doesn’t have that much representation in Whittingham Meats’ own retail cases.

“Guys downtown and the country clubs can afford it,” he admits. “Where your local mom and pop, they can’t charge $50 for a steak. But a lot of guys down here use the burgers, because we do accumulate a lot of the chuck and trimmings.”

So the world hasn’t changed overnight. But it is changing, a burger and a steak at a time.

THERE’S ONE OTHER DIRECTION FROM WHICH Rick Whittingham gets pressure to keep his business modern, and it’s why I’m here. It’s his son Bob, who just rejoined the family business in the last couple of weeks (and promptly contacted Fooditor, figuring that they had the kind of business that would be interesting to me).

Bob grew up around the business—”I’ve always been in it, since cleaning the cutting rooms in grade school. The meat shop is in the blood,” he says. But he went to college at the University of Oregon, and then worked in public relations for a few years in Seattle, perfect training ground for a meat guy full of ideas about making the business more sustainable, local. All those Portlandia things, which make for good-natured back and forth between him and his dad.

“My dad got on the bandwagon earlier than some. But you know, he went to Xavier College down the street,” Bob says. “I bring in a different mentality. Out on the west coast, I saw how everyone was focused on knowing the source of their food, on organic and grassfed meat. I have a real passion for food, I’m always nerding out on the food documentaries on Netflix.”

The next step for Whittingham Meats may represent another major change in what kind of business they are. One of their peers in the industry whom they know well is Peter Testa of Testa Produce, which built a green, LEED-certified plant on land in the old stockyards area. With their 2000 addition at capacity, they’re looking at either further expansion or a second facility, and just beginning to investigate the possibilities of making it a green building. In fact, a day or two after I met with them, Rick was scheduled to have lunch with Alsip’s mayor about the project.

Bob spins some of the ideas they’re talking about for the new plant for me—generating power from their waste, biodegradable cryovacking, and so on. “I’m trying to bring that green mentality back from the West Coast, I was drinking the Kool aid out there,” he says. “But you’re helping out the environment and promoting sustainability with a good facility that’s conscious of environment, and your customers see that.”

Michael Gebert cooked up a couple of Chicago 250 ribeyes, fit for an editor of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.