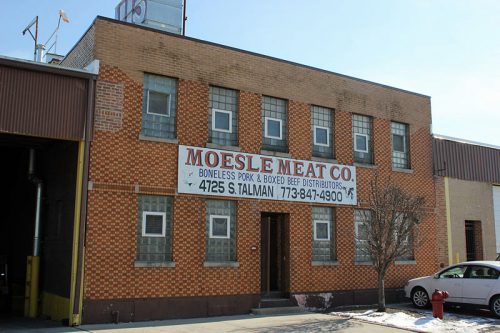

I’VE COME TO 47TH STREET TO TALK ABOUT about Salumi Chicago, the new venture from Greg Laketek, former proprietor of West Loop Salumi, the Chicago-based charcuterie company that enjoyed a few years as a hipster brand supplying bespoke cured meats to everyone from Eataly to chichi hotels and airlines. Instead I find myself at an old school Brighton Park processor called Moesle Meat Co., in a buff-colored postwar building of the type that generically dots the whole neighborhood.

Right place or not? The craggy-faced worker who passes me going out as I go up to ring the doorbell suggests not, but when I ask for Laketek, the Latino woman who answers the doorbell buzzes me in.

Laketek greets me, but then he introduces me to his partner Joel Janecek, who looks more like a finance guy on vacation. Which it turns out is what he is—on permanent vacation from it, maybe. And the story of how Laketek ended up here rather than in a hip neighborhood, in business with what looks like a commodity foods company, turns out to maybe be the most interesting part. Certainly the smartest, from the point of view of how to build and grow an artisan food business in a practical way—so it will last this time.

Joel Janecek and Greg Laketek

WE SIT IN THE SMALL BREAK ROOM BETWEEN processing areas—with its thick tile walls in Industrial Neutral, it feels a little like being sent to an elementary school principal’s office. Janecek explains to me how he came to be the owner of a pork processing plant in Brighton Park.

“I had worked with a few meat processors and flavoring companies on the financial and operational side, and I was tired of traveling around and consulting—I wanted to own a business. My parents had bought and sold businesses before, so I’d seen it done,” he says.

Moesle (pronounced “moseley”) Meat Co. came on his radar as a possible acquisition. A family-run processor, it had started on Fulton Market—”They started out swinging beef but went into pork, because there was no money in beef once some of the big packers like JBS came to town with boxed beef,” Janecek says. They were pushed off of Fulton by rising rents, pushed from beef to pork by changes in the industry, and now the second generation, two brothers and a sister, were close to retiring.

But they were also looking for a way to work out their last few years before turning the business and their employees over to somebody who would keep it going. “I talked to them for about eight months before I convinced them I was the right person,” Janecek says.

The day Janecek took it over, he had a going concern and no immediate need to change it. But in the long term, he knew, “I didn’t want to just do boxes in and boxes out. The business is either volume on the distribution side, or value-add on the processing side.” If you don’t speak business-ese, what that means is, you can either fight against other guys selling the exact same thing at almost exactly the same price. Or you can find a way to make something special that people will pay more for.

I was applying to different jobs in the meat industry. I was just like, I’ll probably never cure meat again.

Because he had a pork processing plant already in operation, “Under those guidelines you already have the USDA tags or bugs, you can basically do whatever you want under them as long as you have the right processes and plants in place,” he says. So often when I and others have written about artisanal charcuterie, the story has been about the struggle to get state or USDA certification for a small-volume product using an artisanal, non-industrial approach. But Janecek already had a USDA plant—and so if, say, he wanted to turn pigs into squiggly little cured sausages instead of boxes of tenderloins and chops, he was better than halfway there. He just didn’t know he wanted to do that yet.

Looks scary, but good mold is where the flavor comes from

WHEN FOODITOR LAST SPOKE WITH GREG LAKETEK, in 2016, it was about how West Loop Salumi had survived two burst pipes in the dead of winter, both of which had flooded his plant and cost him hundreds of thousands of dollars in repairs and ruined product. West Loop Salumi survived that—by bringing in funding from new backers.

What it did not survive, was the new backers.

Laketek doesn’t want to talk about specifics—it closed because it closed. And he was ready to do something else. He was a long ways from the guy I wrote about who had staged for Massimo Spigaroli in Parma:

He worked there for several months, “twelve, thirteen hours a day,” and learned the secret of Italian salumi: no dextrose, no nitrates or nitrites, just salt and, for the sugars, the local wine. “It takes a lot longer to ferment, about three or four days,” versus a dextrose cure which is fully fermenting within about 14 hours. “When you start to ferment something over three or four days, you’re developing other bacteria which are flavor-enhancing.”

The result, in his product, is cured meat that still tastes like the meat it came from, more than it tastes like salt or a lactic acid tang. It’s often softer than you expect from cured meat—maybe disconcertingly so, like meat that’s been left out, since you don’t have the obvious it’s-been-cured cue of saltiness. But taste it and the doubts disappear—it’s beautiful meat (he buys from midwestern farms, these days mostly Slagel), and it’s been treated with obvious respect… and love.

Now Laketek just wanted to find a job. “I was applying to different jobs in the meat industry, took a couple of interviews, and I was ready to carry on to the next chapter. I was just like, I’ll probably never cure meat again.”

In early 2018, Janecek was working with a friend named Steve Gaither on a strategic plan for what he was going to do with Moesle, which he had owned for a year by that point. He knew he wanted to do something where he could build a brand and sell directly to retailers, but what? Gaither, meanwhile, happened to run across Laketek on Linked In.

Laketek says, “I’m applying for jobs and I get this Linked In message that says, ‘Hey man, I like meat, let’s sit down and have a talk.’ And I’m like, okay, that’s weird…” But they agreed to meet on a Friday morning.

Janecek says, “Steve’s calling me, leaving me messages, and I’m thinking why is Steve calling me, he knows Friday at 9 am is my busiest time of the week. What is he thinking? He’s leaving me these long drawn-out voicemails saying ‘this guy’s in my office, you need to talk to him.'”

“We met up that weekend, came over, looked at this place and shook on it,” Laketek says.

It was an ideal setup for growing a charcuterie business—the bills covered by an existing business, with the room for charcuterie to grow inside it and eventually, perhaps, to take it over. Janecek says, “I knew when I bought it there was a lot of capacity—there was capacity in processing, there was capacity in coolers, there was capacity in our trucks.” He was talking with Gaither about what to do with it, but he says, “I wasn’t in a rush.”

And as it turns out, slow-curing meat is an excellent business to not be in a rush in.

Bresaola

LAKETEK KNEW THAT THE MARKET HAD CHANGED EVEN since he first started West Loop Salumi just a few years ago. Despite being taught the Italian ways, he had used nitrates at times in his salumi, but now, “I knew that times were changing, I had to go the clean route,” using non-nitrate cures. He also started using a new form of casing, made from beef collagen and silk, which is more convenient for both makers and consumers, and also means that observers of kosher can eat the beef products (though they are not certified kosher).

The news that Laketek was getting back in the cured meats business attracted attention in the industry. He says, “For a moment there was a chance that we wouldn’t even produce salami or bresaola or any of those products, because a lot of private label companies were interested in us” making retail snack sticks under their brands.

They hit the ground running in March 2018—”We started ordering equipment for the rooms, we started contracting out construction of the rooms. And the timeline just got demolished by our suppliers and our installers,” Laketek says. “We were telling people August, and then October, and I think we finally got it going just before New Year’s.”

“I was just saying, don’t ask. Even my family, I told them, don’t ask,” Janecek says.

I ask if, now that they’re finally producing product, they plan to go after some of the high end clientele that West Loop Salumi once had. “Yeah, we’re talking to City Winery again, I just got a message from [chef] Mark [Mendez],” Laketek says. “He said ‘Hey man, if I drop off a barrel of wine, can you make salami with it?’ Sure,” he says. “We’ve been talking to Marz Brewing for a bit about doing snack sticks with their beer, which is great. But we just want to focus on getting our main product into packages, so the stores can sell them.” (If you’re looking to buy some locally, besides the mail order link, at present they’ll soon be in Plum Market, Eataly, and Mariano’s.)

Those kinds of collaborations are the fun stuff they’ll do when they can—right now it’s about finally getting product to the clients who’ve been waiting for it. Janecek says, “We don’t ever want to tell people we don’t have product again, because pretty soon they stop calling. So that’s step one, the low-hanging fruit, and then step two, who else can we take on and be sure that we can satisfy their needs. That might be private labeling. And then, once we fill out the facility, where can we go next?”

WE GO INTO THE CURING ROOM, A WHITE BOX with enameled metal walls. The smell is, to me at least, one of the best in the world—fresh meat becoming complexly cured meat, like steak and cheese and wine all at once.

Remembering West Loop Salumi’s curing room, filled with racks arranged tightly among each other like blocks in Tetris, this has the emptiness of a suburban megamansion’s family room, only half a dozen or so racks strung with dangling sausages. They look gorgeous to me, but Laketek prods some of the bresaolas, comparing some cured with nitrates (only for comparative purposes) to some using only the new cures, and the new-cure ones are clearly still softer—they’re taking longer to lose moisture and become charcuterie. And any aging process is a bet that good changes will happen before bad changes take over.

He takes one to a table and slices it open—an expensive decision, but the only way to really know what’s going on inside. I have to admit it looks beautiful, and he cuts me a slice. It’s wonderful, meaty yet starting to develop the complex flavors that mark Italian charcuterie as the best in the world. I badly want to ask for another slice, but restrain myself.

Bresaola, freshly cut into

The reason the room is so empty is that even though they’re selling by mail order now—your humble author was, incidentally, customer #1, the first to respond when Laketek announced availability on Facebook—everything we see today is essentially still from the test runs. The day before, they had received 10,000 pounds of fresh meat, which is enough to make 21,000 salamis in a couple of days—marking the start of full-scale production. In another cold room, two of their workers are opening boxes of naturally-raised pork shoulders from Pennsylvania, ripping the plastic off them with a meat hook, and tossing them into a bin for an epic bout of grinding and salting to come.

I ask if the Moesle staff—used to breaking down larger pieces of meat into smaller pieces, not to making Italian charcuterie—has proven up to the task. “We have really good equipment,” Laketek says, which at first sounds like a no. “I have one guy who sticks with me and has become my right hand man, and other guys step in. But also, if you take a chef and bring him into a new restaurant and try to teach him new tricks, he’s going to go against you. If they don’t know how to do it, and you teach them how to do it, that’s the only way they’ll know how. So luckily, we have that.”

The point of starting Salumi Chicago in this building was having enough space—ten times what West Loop Salumi started with, Laketek estimates—but “hopefully we don’t have enough space,” he says. “Joel has workers that are able to hop in on the salumi side, so we’re able to double them up. But we’ve added some pretty big distributors, and it seems that we may be seeing another expansion in the future.”

Which brings with it another concern. The Moesles sold to Joel Janecek because doing so provided a future to their mostly Mexican staff in the Brighton Park neighborhood. Now Janecek is looking for a place to expand in this same neighborhood. “Our employees live here,” he says. “We want to make sure we expand where our employees live.”

As it happened, I still had some West Loop Salumi Spanish chorizo on hand, past its prime, clearly (left). But I tasted this gnarled sample against the new Salumi Chicago product—the paprika taste was the same, obviously, as was the depth of cured meat flavor. The only noticeable difference was a coarser grind on the new product.

Michael Gebert is capo di coppa as editor of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.