Peanut butter and tongue at Mi Tocaya Antojeria, done three ways:

The most intriguing dish, however, is also Davila’s chef-iest. It bears the provocative name “peanut butter y lengua,” and consists of crisped cubes of braised beef tongue in a complex and delicious sauce of peanuts, cured tomato and chile de arbol, accented with bay and cilantro leaves. Rich in flavor and beautifully composed, topped with cooked red onions that provide color contrast to the vivid orange-red sauce, this is as much a must-order dish as anything dubbed “peanut butter and tongue” can ever be.

The dish Dávila calls peanut butter y lengua, which sounds like the casualty of an earthquake in the refrigerator, is an homage to her food-obsessed uncle in San Luis Potosí. A generous slice of beef tongue is braised, pan-seared, and drizzled in a thick salsa de cacahuate that’s similar to a Thai curry.

Dávila isn’t overreaching for originality. Many of her dishes are born out of personal memory and family history. Her uncle’s lengua con salsa de cacahuate is rendered as chunks of pillow-soft tongue (minus the papillae) and seared half radishes drizzled with thick ropes of smooth, creamy arbol-spiked peanut salsa.

Dutiful readers of the city’s restaurant reviewers can probably identify these reviewers for three of the city’s major publications by stylistic notes. Usefully calling out “must-order dishes?” Phil Vettel, in the Trib. Getting off the funniest line (“the casualty of an earthquake in the refrigerator”)? Jeff Ruby, in Chicago magazine. Taking Mexican food with a scholarly bent? Mike Sula, in the Reader.

They may have different ways of expressing themselves, but restaurant reviewers clearly don’t have the diversity of outlooks of, say, political opinions. It’s not like Vettel thinks farm to table is a crock, or Ruby loudly denounces sushi eaters as snowflakes. There’s a reasonable consensus about what’s good and what’s not, and a reasonable parity of knowledge, all told, allowing for individual expertise in this or that.

So if Tronc were to own all the publications named above, as it might well shortly, we wouldn’t be losing anything if that multitude of voices were trimmed down to one, right? They all liked the peanut butter with tongue dish, what do we need three of them for?

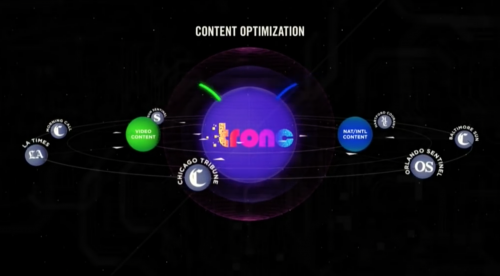

THE POSSIBILITY THAT TRONC, BY ACQUIRING WRAPPORTS, could shortly own nearly all the major print media in Chicago—this tweet from Scott Smith shows a pretty complete list—has excited lots of debate, mostly focused on the two daily sources of hard news being under the same roof (and leaving the Reader to complain, what about us?) But we all have our beats, so of course I’m thinking about food coverage. And precisely because food is not one of the self-appointed central missions of a newspaper, thinking about it reveals some things about how a Tronc future could drastically change what kind of media we get, about food and plenty of other things.

When it’s all just content, there’s little need for an overarching brand that stands for something, because every piece of content is an island floating on Facebook.

It wasn’t that long ago that the Justice Department was preventing the Tribune and the Sun-Times from being printed together, the mingling of paper and ink seen as a threat to papers representing different political constituencies, an idea considered essential to democracy.

TV was already changing that by the 1950s; there was less difference between papers than between people who got news from paper and people who got it from TV. But it was never just about headline news. Every publication was a full lifestyle, aimed at a specific group whose tastes were reflected in sports, in comics, in society coverage, in the arts, and in how they covered food. At the Republican Tribune, Paul Camp told businessmen where to spend their expense accounts. At the working class Sun-Times, Pat Bruno told you where to take the wife for a nice Italian meal for your anniversary. In glossy Chicago magazine, Allen Kelson informed sophisticates about Charlie Trotter and Jean Banchet. In the gritty Reader, Laura Levy Shatkin led yuppies to younger chefs and ethnic discoveries.

Like the carefully cultivated distinctions between Buick and Pontiac (that car buyers stopped caring about as they bought Toyotas instead), a lot of these distinctions have faded with time. Put everybody under one roof and in some ways you’ll increase diversity—of coverage. After all, three reviews of Mi Tocaya Antojeria means some other potentially worthy place isn’t getting covered.

There’s a fourth major-publication reviewer who didn’t review Mi Tocaya, Michael Nagrant of Redeye, and he says that since Redeye went to a weekly format (and more of its content runs in the Tribune), they’ve started a certain degree of informal coordination to ensure that the Trib and Redeye reviews usually don’t overlap. The week Vettel reviewed Mi Tocaya, Nagrant covered Tex-Mex at The Texican, and you could learn something different worth knowing from both.

AND THAT’S AS FAR AS IT’S GOING TO GO! newspaper people were quick to insist. Kevin Pang tweeted (in response to Scott Smith above), “Sorry, but to suggest my courageous colleagues at the Trib, Sun-Times + Reader don’t have editorial independence is a ridiculous assertion.” Josh Noel of the Tribune tweeted, “Told a top editor recently that a story would likely get a lot of page views. He didn’t hesitate. He said: ‘We don’t write for page views.'”

Well, you get a lot of hits for avocado toast at the Tribune, for a publication that doesn’t write for page views at all; and obviously clickability is driving things like monthly themed food slideshows at the Trib. Which is not in itself a sin—you can write smart things in a caption as well as anywhere else.

But in any case, this is all about today. And if Tronc is about anything, it’s about the future, forward, not backward, twirling towards freedom! Actually, I don’t know what Tronc is about and neither does anyone else; since its much-parodied video a year ago, which Slate (no stranger to a clickbait future) described as “an unrelenting circular saw of vapid media-consultant clichés,” there has been little visible progress toward a future in which journalism is fed into a funnel and then optimized, into delicious snack patties for your dog. (I’m quoting from memory here.)

From the Tronc video

What we do know is that when it’s all just content, there’s little need for an overarching brand that stands for something, because every piece of content is an island floating on Facebook. As I was writing this, a piece in Flavorwire had similar thoughts about the way Netflix treats the art of movies as, basically, so many kilowatt-hours traveling the wire:

The problem is, you can’t appeal to these people’s sense of cinematic history or cultural responsibility, because they don’t have any. Increasingly, those who are custodians of cinema and television don’t see it as an art – they see it as content, to be data-cized, targeted, and delivered. The contents of the content are inconsequential.

And if that’s true of great art like The Godfather and Road House, it’s only moreso of politics and culture and, well, writing. People were Tribune or Sun-Times households, in their time, because the content, in aggregate, said something about who you were and how you approached the world.

But nobody feels the slightest bit that way about the Orc-armies of anonymous clickbait that swarm Facebook (“You saw those baby meerkats on Whoozi.com? Sorry, I get all my news about celebrities whose net worth stuns me from Smackmyfacedaily.com, we can’t be friends any more”). Perhaps the only online brand like that created in recent times is Medium.com, which has successfully carved out a space as the online equivalent of a celebrity wearing glasses to look intelligent.

The thing is, there’s nothing about a world of continuous content spewage into the optimization funnel that supports the traditional virtues of a newspaper with a point of view on things like restaurants. Hot new restaurant opens! Then reviewer goes and writes, well, actually it kind of blows. All that’s going to do is irritate people who want it to be good. Why does reviewer have to be such a grouch?

Much better to generate five different pieces of content about its hipness, about what to drink, about the five hottest places to party in River North right now. It’s not like that stuff isn’t getting written anyway—all those “First Look” articles aimed at partying twentysomethings are already anti-reviews, based on the fact that they (supposedly) don’t want to read criticism, they want to know what’s hot.

Now imagine a future in which 20 pieces like that, 50 pieces like that, get generated each day, each grabbing a little bit of the audience to add up those clicks. Having one authoritative, learned voice is not only not worth the investment, it’s contrary to the whole point of keeping the audience happy and clicking by never offending anybody. It’d be like expecting Clear Channel in radio to take a strong pro-Steely Dan, anti-Fleetwood Mac position. Are you trying to make people turn the dial?

Maybe there’s money to be made at that, but it’s not about anything, it doesn’t mean anything. Rich people used to start newspapers to stand for something; now it seems some very wealthy people are interested in owning all the newspapers at once for the precise purpose of saying more nothing than ever before, of chasing eyeballs with baby animals and security cam videos. You may be amused, you may click “Like,” but you are not going to know more about Chicago’s restaurants (among other things) as a result.

And that should bother diners, restaurateurs and anyone else who cares about… anything, really. A content optimization funnel? There used to be another word for that kind of image: a black hole, from which nothing with any weight to it can escape.

Michael Gebert is Chief Funnelizing Officer of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.