IT’S FRIDAY NIGHT AND THE LIGHTS ARE AGLOW inside Nonna Silvia’s Trattoria and Pizza in Park Ridge. To get inside, you have to get past a line of people picking up cardboard boxes of pizza from the takeout window. The boxes are decorated with an illustration of a checkered red tablecloth Italian restaurant, so familiar that no one actually sees it. Italian restaurants don’t really look like that any more; what they look like is Nonna Silvia’s—exposed brick, decorative orange-dappled walls that signify a Tuscan village, Italian art moderne posters for Peroni or Cinzano.

And a crowd, boisterous and happy. It’s Friday night, and those with higher ambitions for a night out than pizza and Netflix are out at Park Ridge’s most popular Italian restaurant. It’s barely out of town—the city starts on the other side of Canfield—yet it feels like something that’s gotten kind of rare on Chicago’s food scene, a restaurant full of regulars. Nobody has the look of not being sure what the restaurant specializes in; nobody has to be asked if they’ve dined with us before, or to have the way the menu works explained to them.

There’s solitude at the bar, and laughter at the tables, and family conversations as unselfconscious as if they were taking place at home. John Giannini, one of the two chef-owners, who’s 36 and could pass for a decade younger, comes out and chats up a table of older folks who probably remember him as a kid. Waitstaff whips between tables with plates like toreadors dancing around bulls, while in the tiny kitchen, they’re dishing as many dishes into to-go containers as onto white china, in this age of GrubHub.

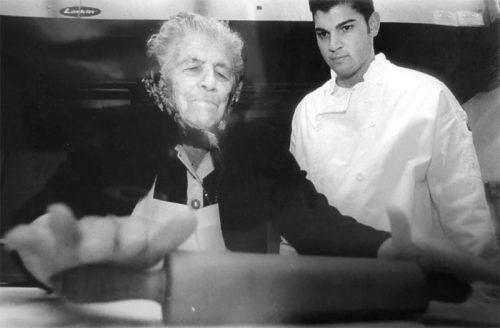

John Giannini at table side

The menu is—well, we don’t really have a word for it, so we have to give it a bloodless hybrid name, contemporary Italian-American, I guess. There’s not really much old school, Grandma’s red gravy Italian-American on the menu (Nonna Silvia wasn’t that kind of grandma), though John tells me they sell a lot of spaghetti and meatballs on Sunday.

To me, this is what Italian food was in Chicago in the 90s, fresh pastas and vegetables and herbs, fairly authentic versions of things like saltimbocca and fried calamari, some trendy American things (I know Italians make ravioli with squash, but it probably doesn’t have the Mrs. Smith’s pumpkin-ness of the ubiquitous 90s pumpkin ravioli). Lighter than old school Italian, with more seafood and chicken, but likable and accessible, without the dare-you-to-eat-it offal meats and other things of more recent Italian cheffery.

I have to admit I miss it; the places I used to go for it, Da Nicola and Oo-La-La and La Donna (which, as it turns out, Giannini has a family relation to), are long gone. So I’m at Nonna Silvia’s tonight, not because I think it’s a place everyone needs to rush to like it’s a hot opening in River North, a culinary wonder full of dazzling new twists. It’s not, and anyway, they don’t seem to need your fickle trend-chasing business, not this night anyway.

I’m here because it’s the kind of place everyone should have, the neighborhood Italian spot, welcoming and reliable and guaranteed to satisfy everybody. Everyone should have one, and we all used to, but much of Chicago seems like it got too hip for them.

Park Ridge, tonight, is not too hip for a good time with Italian food.

Courtesy Nonna Silvia's

Courtesy Nonna Silvia's John Giannini and Nonna Silvia: “I was 19 years old, she was 95 years young.”

IT’S BECOME A RUNNING JOKE THAT EVERY new Italian restaurant, no matter who owns it, will tout something from “Nonna’s original recipe” on the menu. But Silvia Giannini was a real nonna for both of the owners of Nonna Silvia’s, and even worked in the restaurant named for her for its first couple of years before she passed away.

Which is by way of saying, co-owners and chefs John Giannini and Steve Marti are not just business partners, they’re practically brothers. They call themselves cousins, because they’re close in age (Steve is seven years older), but technically they’re a generation apart—as John explains it, “My grandmother was Nonna Silvia’s oldest daughter, and Steve’s mother was the baby sister.”

They grew up together—literally, in the same building—and came of age in the restaurant business together. The family goes back to Abruzzi e Molise, the wheat growing region east of Rome—”It’s kind of undiscovered for tourists, but they make all the cheeses and pastas, and it’s laced with olive trees and mountains,” John says.

Idyllic-sounding but, in the 1970s, economically depressed, so family members started emigrating to the northwest side of Chicago. The younger ones found work in construction and in restaurants; the older ones like Nonna Silvia simply came here to retire among their families. “They were farmers,” Steve says, by way of explaining why they found what work they could. “The whole family used to live together in a three-flat in Portage Park—my parents lived on top, his grandparents and dad lived on the bottom, and my aunt and uncle lived in the middle with Nonna Silvia and my grandfather.”

By the first generation born in America, to which John and Steve both belong, restaurants were in the blood. Steve’s brother became a chef for United, and owned a restaurant in Elmhurst; John’s mom remarried into a clan that had a number of northwest side and suburban restaurants, like Via Veneto and Pescatore Palace in Franklin Park, as well as Sapori in Lakeview and La Donna in Andersonville. “We started very young,” John says.

“My first job was $3.20 an hour,” says Steve.

“Dishwasher, salad boy,” says John. “Bus boy, cook, host—”

“I had one of those orange tarps, and I was cleaning calamari—”

“Caterer, delivery driver, you name it.”

In that family, it took them only as long as till John graduated high school before they thought about opening their own place. “We always got along really well, and right out of high school, we had an opportunity because one of my friends’ dads had a restaurant and my friend told me, he’s looking to get out,” John says. “It was 800 square feet, the overhead was low, it was like $850 a month. I was 18, Steve was 26. We paid my friend’s dad for a few pieces of equipment, we scrounged up as much money as we could—”

“Maxed out our credit cards—” Steve says.

“—and opened in 2000.”

That was in the middle of the block where Nonna Silvia now anchors the corner. “Seven tables in the front, carry out and delivery, very simple, pizza, salads and pasta,” John explains. They couldn’t serve wine or beer until John turned 21. But for those first couple of years Nonna Silvia, for whom they named it, was there, making biscotti and providing visual assurance that the in-house Italian knowledge ran deeper than two green kids. I asked John why they chose her, out of their house full of relatives, to name it for.

“We grew up eating her food, and appreciating it and working with her in the kitchen,” he says. “She always made everything from scratch. So we named the restaurant after her. The pasta recipes, the marinara—those are all pretty much hers.”

Perhaps because stakes and expectations were so low, the restaurant survived and prospered. “People thought we were crazy doing it,” Steve says. “But John’s mom worked at Via Veneto his whole life, and he was there every day after school.”

“She was a career server for forty years,” John allows. “Still doing it.”

“Yeah, but she wasn’t just a server, she watched the whole restaurant,” Steve insists. “That’s her brother’s restaurant, and she basically watched the front while he was in the back cooking. That was like a 400-covers-a-night restaurant, right?”

“Sometimes,” John says. “I mean, James Ward used to go there, Pat Bruno, Sherman Kaplan,” he adds, reeling off a roster of 1980s critics, most now gone, who loved their Chicago Italian food. “The economy was better then. There were some good years.”

She always made everything from scratch. So we named the restaurant after her. The pasta recipes, the marinara—those are all pretty much hers.

Well, the economy is always better for some restaurants than others, the ones that seem right for their times, and as spaces opened up in the building, they took them over for Nonna Silvia’s, turning the pediatric office on the corner into the kitchen and main dining room, and then the barbershop next door into a second dining room and private dining room for things like corporate events. “Because of the construction background in the family, Steve, his brothers, his dad and I built it out as we were still running the little place,” John says.

I ask them to take a crack at what genre they think it belongs to. “I think we picked the things that we liked from the restaurants we worked at, and added our flair,” Steve says.

“We know the old school spaghetti with meatballs, and sausage and peppers, and fettuccine alfredo,” says John.

“But you can get that anywhere,” says Steve.

“Really, where it’s at is our seasonal specials,” John says. “All the Swiss chard in the summer is from Steve’s dad’s garden, and we even freeze it and puree it in the winter—we use that to make the Swiss chard fettuccine. Then, in the winter time, it’s the peasant food that we grew up with that our parents made—the polenta, the wild boar ragu we put on special sometimes, root vegetables. And then in spring and summer, there’s a farmer’s market in Park Ridge that I go to every week and I grab whatever I can—”

“Tomatoes that you just can’t get in the winter,” Steve says.

“Baby eggplants, peppers—Steve’s got a place in Wisconsin so they go up there and get stuff from their farmers market—”

“Ramps, stuff like that,” Steve says. “A little bit of our personal flair comes from hunting—that’s why you’ll see game, quail, stuff like that on the menu.”

I ask if they’ve seen their audience get more adventurous over time in trying unusual meats and cuts, or the like. “Absolutely,” John says. “The stuff that we tried ten years ago that didn’t go over, is working now. We made squid ink pasta, I didn’t think it would sell—we can’t keep up with it. We have a lot of regulars, and I think we’ve built up trust.”

“Eight or ten years ago we got pork belly from Chicago Game & Gourmet, and everybody’s looking at it like we’re crazy,” Steve says. “We did a sea urchin pasta and they’re… I’m not doing this. You know, it just takes time.”

I’m curious about the dedication to seasonality. Was that something they talked about doing when they first opened, or did it develop over time?

“That’s all we knew,” John says. “It’s what we grew up with. So like right now, our moms would be doing stuff now with the cardoni, which are the artichoke stems. Now the asparagus is going full swing, so we go by our mom’s houses and they’ll have a big plate of grilled asparagus.”

“We used to pick wild asparagus by the side of the train tracks and jar them,” Steve says. “Now fishing season is starting, so we’ll have fresh trout on the menu, because that spring trout is what we had.”

“Him and his dad still go fishing all the time,” John says.

“We don’t obviously bring it here because you can’t,” Steve says. “But different seasons, different pastas.”

Seasonality and farmers market produce, odd cuts, even foraging… you know, what’s interesting about this 90s Italian throwback food is how 2018 it is.

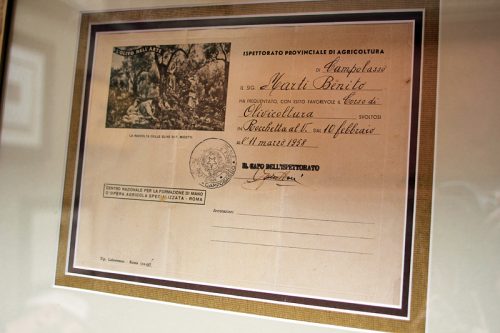

Steve Marti with his father, Benito

THEY’VE HAD THE RESTAURANT 18 YEARS NOW, long enough to grow up in it as men—from starting with just the two of them they have a family of employees now, and each has a family of his own: Steve has a son, John has a daughter. “We split the time a little bit more, where before we were always together,” John says. “But one of us will always be here.”

So the restaurant and its owners shift, inevitably, toward the future generation. But this is a family restaurant, and even if Nonna Silvia is gone, the elders who shaped it aren’t done with it yet. A week after dining there, I return during the day to interview John and Steve, and to meet Steve’s dad, Benito Marti. It wasn’t to interview him, though, because despite having been in America since 1974, he doesn’t really speak English.

For me, so much of food writing is about uncovering cultures hidden in plain sight in Chicago. Yet it’s still kind of astonishing to me that you can spend 40 years in an entirely Italian-speaking enclave within Chicago, and never really be exposed to enough English to even be able to half-speak it. But I look at this man who spends his time growing herbs for his son’s restaurant in the summer, and goes fishing for trout with him, and helped build the restaurant (he did a lot of the brickwork, John says), and spends time with his family… and I can’t think what, exactly, I’d tell him he missed in the English-speaking world. (Oh, if only you were on Facebook, sir…)

The only thing he’s actually missing today, Steve explains, is that because he’s recently had some medical issues with his eyes, he’s had give up his driver’s license at age 85. This must be a hard blow, but his is a face of such stoicism that I would never have known it, a Roman statue’s visage of determination and lines etched deeply by work in the sun.

Benito was a farmer, and a sheep herder (“When he was a kid they’d give him half a loaf of bread and send him off for a couple of days to feed the sheep,” Steve explains), and a hunter who would shoot quail and trade them for other foods in the village. And he was a producer himself of food—his certification as an olive oil producer, dated 1958, hangs on one wall of the restaurant.

Sixty years later, he still is. He grows vegetables and herbs for the restaurant in his oversized backyard—zucchini flowers, and heirloom tomatoes, and squash and Melrose peppers and string beans (“with fresh olive oil, they’re fantastic,” Steve says).

He makes the gnocchi a couple of times a week, usually coming in at 5 in the morning to get it done before anyone else shows up. With some lifting help from his son, he fills an industrial mixer bowl with potatoes, “00” flour, and just enough water by sight or feel, and mixes it. Then the dough is dumped onto a counter and he starts tearing off chunks, which he kneads for a few minutes and then rolls out with a rolling pin.

He makes ropes of dough, finger thick and about a foot long. With a handheld blade—given his construction background, my guess is it’s an ancient spackle knife from a hardware store, normally used for plastering—he neatly snips off pieces, an inch long each. Then, surprisingly, he uses his thumb to make a little divot in the middle of each one, smearing it slightly as he does so, to give it a little pocket and some irregularity, to hold the sauce in the final dish.

I soon have enough photos of this process to more than satisfy my needs, and I feel a little guilty leaving him to this work for hours to come that morning. He says nothing—but then I wouldn’t understand it if he did, most likely—and continues in his work as I go off to interview his son and nephew.

When I come back, a half hour or more later, he’s filled trays with hundreds of these little gnocchi, and by the look of what’s in the bucket, he will make hundreds more today, every one by hand. There are very few Italian words I know to say for what he’s done this morning, partly for my camera, and I say a couple of them. He nods, just the faintest hint of a smile cracking his stone visage.

But I know one thing, in any language. This isn’t the Italian restaurant that slick magazines or international dining guides will lead you to. This is the neighborhood Italian restaurant you would be lucky to have near you. You would be lucky, to have this man and his son and nephew working every night to make dinner for you.

Grazie, signor Marti.

Michael Gebert is il Gattopardo of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.

Great article! I remember 2000. Eating pizza with small space heaters keeping our feet warm. I think Gina? used to be our server. We loved it and still do. I will keep visiting until they bring me my last “goodbye limoncello”.

Nonna Silvias is a fantastic restaurant! Chef Steve and Chef John are simply the best as is their staff!!! We love the food, the wine, the atmosphere, and most of all the people (staff and customers). Nonna Silvias is worth the trip from wherever you are coming from.

You need to visit more often – Yes!! Let’s make a reservation for the next wine dinner on 1 May 2018 – Oh! I have already made mine!! :<)