SANDRA LACH ARLINGHAUS REMEMBERS HELPING her mother make Thanksgiving turkey as a teenager. But this was no ordinary roasted bird. Her mother was noted chef, cookbook author, and food consultant Alma Lach, and the entire breast was covered with a tapestry of delicate tulips, lilies of the valley, and other flowers carved out of vegetables and coated with gelatin. The leaves and stalks of the lilies of the valley were made from green onions, and the tiny bell-shaped flowers were stamped out of hard-cooked egg white using the metal end of an old pencil with the eraser removed.

“It was a fantastic presentation,” Arlinghaus recalls. “My mother was a real artist with food.”

Now everyone can appreciate that artistry thanks to Arlinghaus, an adjunct professor of mathematical geography at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and her husband William. After Alma Lach died at the age of 99 in October 2013, they donated her collection of more than 3,000 cookbooks, personal notebooks, papers, cooking accouterments, and ephemera to the University of Chicago library in Hyde Park—which already had her father’s papers and books, the Donald F. Lach Collection of historical material relating to Asia’s influence on Europe.

Alma Lach Papers, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library

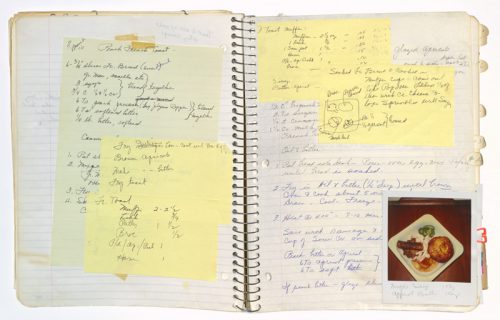

Alma Lach Papers, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library Notes upon notes, c. 1986

“We gave the whole collection to the University of Chicago because we thought it was a resource that should not be broken up, and this was a wonderful way for my parents to be together in perpetuity in a place they loved,” Arlinghaus explains.

The exhibition “Alma Lach’s Kitchen: Transforming Taste,” which opened in September and continues through January 6, 2017 in the recently renovated 2,384 square foot Special Collections Research Center Exhibition Gallery at Regenstein Library, 1100 E. 57th street, includes only a small fraction of the material, but it’s enough to show that Lach was an extraordinary woman, especially for the mid-twentieth century.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974. Alma Lach Culinary Library, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974. Alma Lach Culinary Library, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library Alma Lach, from the back cover of Hows and Whys of French Cooking

ALMA LACH’S CAREER GOT UNDER WAY IN THE late 1940s, when she and Donald returned to the University of Chicago, where they had met a decade or so earlier while living at International House, for him to teach history. They lived in Hyde Park for the rest of their lives, though Alma got a second home in Ann Arbor (to be nearer Arlinghaus) seven years after Donald died in 2000.

At age six or so, Arlinghaus, now 73, was the inspiration—and recipe tester—for her mother’s first cookbook, “A Child’s First Cook Book” (1950). Her memories range from making “candle salad,” featuring a cherry-topped peeled banana standing in a ring of canned pineapple, to a carrot-cutting “lesson in knife skills” interrupted in real life by a bolt of lightning striking the cross atop a turret on Harper Library across the street, resulting in a loud noise that caused the knife to slip. “The cut was serious enough to require a bandage and taught me the importance of having a steady hand,” she says.

“She never really cooked from recipes; she just collected them.”

Lach wrote three more children’s cookbooks: “The Campbell Kids Have a Party” (1954), “The Campbell Kids at Home” (1954), and “Let’s Cook” (1956). She also created, produced, and starred in her own 1955 children’s cooking series, “Let’s Cook,” first broadcast on WTTW and then on WGN-TV. It was the beginning of many television appearances over the years. The first case in the exhibit, which was curated by Eileen Ielmini, Brittan Nannenga, and Catherine Uecker, along with exhibition designer, Joseph Scott, is devoted to these early efforts, including the manuscript for an unpublished cookbook for men.

New York: Hart Publishing Co., 1950. Alma Lach Culinary Library, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library

New York: Hart Publishing Co., 1950. Alma Lach Culinary Library, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library Rare books librarian Uecker was responsible for selecting the cookbooks from Lach’s collection that share the main wall display case with a sampling of her cooking utensils, carving tools, recipe boxes, molds, a treasured terrine, and other kitchen paraphernalia. They range from books on Greek, Polish, Russian, Chinese, and other world cuisines to eclectica, such as “Shed Pounds with Cocktails and Gourmet Fare,” “The Gun Club Drink Book,” and Mimi Sheraton’s “The Seducer’s Cookbook.” “We wanted to show the variety of her interests, among them church cookbooks, international cooking, and food and vegetable carving,” Uecker says. “The carving was tied to Chinese cooking, which she was researching for another cookbook of her own.”

Uecker says her favorite cookbook was too fragile to display but is mentioned in a text panel. “It was handed down to Lach by her mother and is so heavily annotated and crammed full of notes that it’s twice the original size,” she says. “It really shows where Alma came from and how she got started, although she never really cooked from recipes; she just collected them and wrote her own.”

Alma Lach Papers, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library

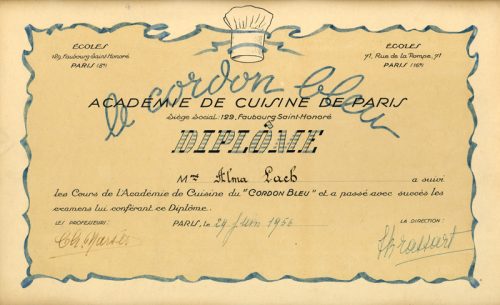

Alma Lach Papers, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library AS IT WAS FOR JULIA CHILD, WHOM SHE met but did not become friends with (according to Arlinhgaus), Le Cordon Bleu cooking school was a life-changing experience for Lach. When her husband won a Fulbright Scholarship to study in France in 1949, the family lived in Paris for three one-year periods. Like Child she attended cooking classes during the day and, in the evenings, duplicated the dishes at home for Donald and Sandra. She filled several spiral-bound notebooks with her schedule, notes, and French recipes, and Ielmini, assistant university archivist, says they are among her favorite items in the exhibit—where they sit near the Grand Diplôme she received in 1956, one of the first Americans to earn that honor.

Also like Child, Lach wrote a French cookbook. “Cooking à la Cordon Bleu” was published by Harper & Row in 1970, but when the school objected to her use of the name without permission, it was revised, expanded, and republished in 1974—this time by the University of Chicago Press—as “Hows and Whys of French Cooking.” “It was the first cookbook the press ever published,” says Uecker, who points out that the main difference between Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” and Lach’s book is that where Child focused on teaching traditional French cooking to Americans, Lach focused more on making French cooking understandable to American palates.

The show as a whole is organized to highlight the main themes that emerged as the curators sifted through more than 350 boxes of materials. There are sections on Lach’s stint as Chicago Sun-Times food editor from 1957-1965, the cooking school she opened after that, her many awards and accolades from professional organizations, her world travels to places like India and Italy, and her consulting work for clients like Flying Food Fare, which made the food for Midway Airlines, and Chicago restaurants, such as The Berghoff and The Pump Room (see below). A slide show of her photos—she was a terrific food photographer—supplements the displays in the cases. “She was always learning and writing, about truffles, where cinnamon sticks came from, what the Maxim’s that opened in Beijing was like… about all sorts of subjects,” Ielmini says.

One of the quirkiest examples of Lach’s role as a businesswoman is her 1995 invention, the Curly-Dog Cutting Board, which gets a display case of its own. The device cuts a hotdog partially through into segments, so it can be curled into a circle and fit on a hamburger bun. If you happen to be in Meridian, Mississippi, you can see the results at Brickhaus Brewtique, where the half-pound Monster Burger is topped by a Curly-Dog, beerkraut, bacon, cheeses, and more. Not co-incidentally, the restaurant is owned by Arlinghaus’ son, Lach’s grandson, William, who has some of the kitchen equipment that didn’t go to the university.

His son, David, the bartender at that establishment, has created a “beer tail” that’s being served at a Nov. 2 fund-raising dinner at the library to support the collection. The brew is a blend of Mississippi craft beers that tastes just like Scotch, Lach’s favorite libation, and it’s called… the “Alma Mater.”

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974. Alma Lach Culinary Library, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974. Alma Lach Culinary Library, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library Flower design illustration, Hows and Whys of French Cooking

Rich Melman Meets Alma Lach

Around the time Richard Melman, founder and chairman of Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, opened The Pump Room in 1976, he hired Alma Lach as a consultant. “I was a kid and realized I didn’t really know what good food was,” he recalls. “She knew so much, I was enthralled. Her job was just to teach me about food by cooking for me, taking me places to eat, and sitting around and talking. She did this for about a year until I hired Gabino Sotelino as chef.”

Matchbook, c. 1970s

One of Melman’s most vivid memories is learning about caviar. He’d put it on the salad bar at R.J. Grunts, his first restaurant, but admitted to Lach that he didn’t know why people got excited about it because the $8/pound stuff he was using tasted awful to him. “She introduced me to great caviar, and fine smoked salmon, and foie gras. Every Sunday for months, my girlfriend (now wife) Martha and I would have them for brunch,” he says. “We’d often drink Champagne, and it was a real thrill, because we were so young.”

He took the crappy caviar off the salad bar and says Lach also influenced LEYE restaurants in other little ways. “She played around in The Pump Room kitchen a bit, but restaurant kitchens weren’t her real strength,” he says. “Also, she was a serious person, and I don’t think she liked the fact that I joked with her a lot.”

Melman adds that Lach gave him some advice that was right on the mark, though he didn’t follow it then. “The most untapped source of food I know is Chinese food,” she said. “It has so much depth, you ought to start thinking about it.” Today Lettuce has the Big Bowl chain, sushi restaurants in Chicago and through its airport division, and just this month launched a dim sum menu at Intro, as well as hosting a Japanese chef, Hisanobu Osaka as chef in residence at the same restaurant.

Courtesy Intro Chicago

Courtesy Intro Chicago Shrimp toast at Intro, dim sum menu

Anne Spiselman is a freelance writer who has covered food, wine, and culture for decades. She’s a frequent contributor to Crain’s Chicago Business and Edible Chicago and has written for most local publications and some national ones.

COVER IMAGE: Alma Lach, photograph, ca. 1980, Alma Lach Papers, Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago Library

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.