EZRA STOKES PICKS UP HIS BROOM and sweeps the dust off the wooden floor of his shop at 28th and Frome. A modern janitor’s brush would do it faster, but he wields the old broomcorn stick with surprising grace, a cloud of dust disappearing out the front door. Outside cars go by with low motor noises, but once the door is closed, Stokes lights his oil lamp and takes his place behind the counter in a silence that could have come from another century. “Looks like a nor’easter,” Stokes observes.

“Is that bad?” I ask, for lack of anything else.

“Good or bad, that’s for the Almighty to say, not I,” Stokes muses, tamping his corncob pipe.

Few customers come into Stokes’ shop these days, as the old Yankee population on the South Side dwindles to the last dozen or two families, now squeezed into just a couple of blocks. Only one restaurant, Hawkethorne’s Fo’c’sle, survives in Yankee Town, serving scrapple and pease porridge just five days a week.

There’s still a trade in antique scrimshaw among LaSalle barristers, eager for a piece of one of the industries that built Chicago as a powerhouse. But you wouldn’t call it brisk, exactly, and it’s hard to see on what economic basis Yankee Town has survived as long as it has. With each brush of Ezra Stokes’ broom, a little bit of Chicago history is swept away.

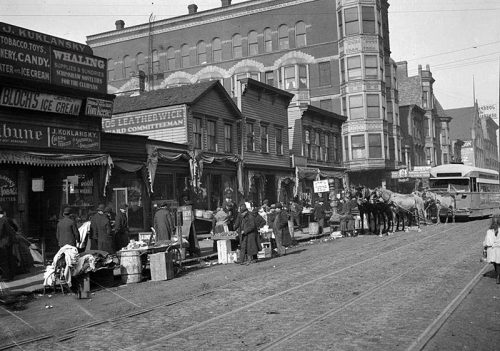

28th street in Yankee Town, with horse-drawn bus visible, c. 1938

BOUNDED BY KEDZIE, 26th, HOLTON AND Piddlebury, Yankee Town was founded in the late 19th century by a group of Quiverers, an offshoot Pentecostal-Prelapsarian sect who’d become disgusted with the godless decadence of central Connecticut. They split off and made their way west and purchased what was then eleven acres of prime farmland outside the borders of Chicago.

Their intention was to farm it. It was only by chance that they arrived in Chicago during the height of the lake whaling industry, at a time when the massive cetaceans which once spouted in Lake Michigan were fetching top dollar on the Chicago exchange. Most Yankee men had “gone t’sea” at some point in their lives, and the newly arrived Quiverers soon split between those determined to follow a calling to farm, and those who were lured by the promise of blubber-oil wealth on what poet Hamlin Garland would call “the blue prairie of Illinois shores.”

Whalers slicing out blubber on the shore of Lake Michigan, c. 1920

Electrification and depletion of the whale stocks would spell an end to the whaling boom (the trade in whale meat was, of course, outlawed entirely in 1951). But Prohibition gave the naturally abstemious Yankees an unexpected degree of clout—no cops needed to raid Yankee Town looking for hidden stills. This was the heyday of Yankee Town’s most powerful boss, Alderman Amos “The Crofter” Leatherwick.

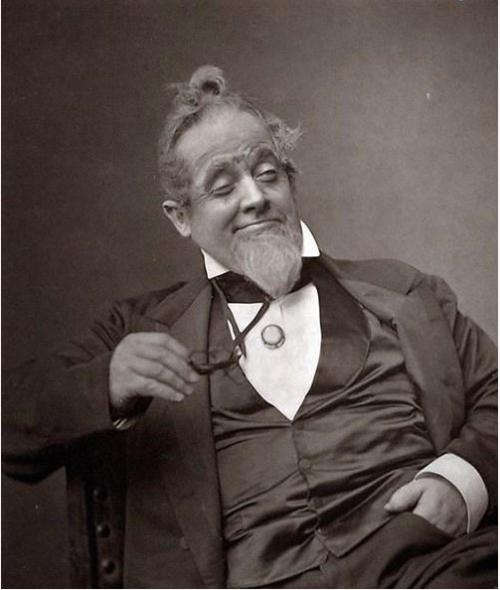

Amos “The Crofter” Leatherwick

Seeking to preserve the old Yankee way of life, Leatherwick fought a rearguard battle against modernity for nearly 30 years. As the rest of the city indulged in modern plumbing, Leatherwick kept it out of Yankee Town, employing local ragamuffins to deliver pails of water to Yankee Town homes. When the 28th street bus sought to come through Yankee Town, he used an old covenant barring motorized vehicles to force the Chicago Rapid Transit company, forerunner of the CTA, to shut the bus off and have it pulled by horse for four blocks before resuming powered service.

The Crofter’s reign came to an end when some of the younger Yankees, like Makegood Pleasance, who owned the Think-No-Ill-Thoughts Tearoom, sought to introduce modern innovations (like the gas stove). This led to a rupture in the community that took the usual Quiverer form—the north side of 28th street in Yankee Town split off from the south side, calling themselves the Free New Covenant Yankee Merchants Association of Unabashed Godliness.

Whether the young Yankees like Makegood Pleasance could have wrested control of the neighborhood from The Crofter is one of Chicago history’s great what-ifs. Within the month, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. As the nation geared up for war, the city forced innovations on a divided Yankee Town that they’d long been thwarted in realizing. No longer would boys roll barrel hoops down 26th without worrying that anything faster than a team of horses pulling a bus would come their way.

HAWKETHORNE’S FO’C’SLE IS A TINY white clapboard luncheonette, that looks like it should be topped with a widow’s walk; today the widow in question, Elspeth Hawkethorne, dressed all in black, was behind the counter, clutching the business’s tin box from atop her stool. The rest of the staff was a pair of Mexican cooks, and save for her severe visage, there was little to distinguish this establishment from any other diner in town. Well, except for the four traders in their yellow coats, clustered at the end of the row of stools. Someone made a big score and came down to Yankee Town for a scrimshaw memento, I guessed.

I scanned the menu—Yankee pot roast, and pease porridge, and Aroostook potato stew. A hand-lettered yellow sign called out another item, a special of Lake Steak, for a surprisingly high price of $22.99. My curiosity aroused, I asked what it was.

“Sorry, boss, all gone,” the cook said.

I could see why—all four of the traders were chowing down on the thick filet of seared meat. Then an older businessman type walked in; he nodded to the grill cook, and I saw him pull another slice of the ruby red meat from the cooler and place it on the grill.

“It’s a special kind of steak raised on Lake Michigan, up toward Mackinac,” he said. “Very unusual flavor. Mostly the old-timers like it.”

“Is that the Lake Steak?” I asked. “I thought—”

“He called ahead,” came a peremptory answer from the proprietress. “As others might be well advised to do, out of politeness,” she added.

I ordered the Yankee pot roast, but as the older businessman received his plate, I asked my companions generally, “So what makes this a Lake Steak?”

There was an audible choking noise from one of the traders, who thumped his chest and coughed to clear his throat. “I—I—” he said. “I’m not really sure—”

“Go on, dude, tell him,” another said, to which a third added under his breath, “Yeah, don’t be a dick, mopey.”

The newcomer finally answered. “It’s a special kind of steak raised on Lake Michigan, up toward Mackinac,” he said. “Very unusual flavor. Mostly the old-timers like it.”

“Curiosity killed the cat,” I heard the owner say behind me.

A sailor came in to ask a question, and the proprietress stepped out for a moment, clutching her tin box. The older gentleman and I exchanged a look, and then he slipped a slice of his steak onto my coffee saucer. I palmed it and then popped it into my mouth. I expected little of the meat, given its lack of marbling, but I was impressed by its flavor, more like game than the usual corn-fed diet, and even a briny note, like an oyster.

“Does it taste like that because of its diet?”

“Must be,” he replied. “I believe they eat close to the shore. A lot of seaweed.”

“And wooden puppets,” it sounded like one of the other four said, which earned him a vigorous smack on the upper arm. It didn’t deter the others, though, because they were soon making mock as well—”And peg-legged sea captains,” said another.

There was a cough from the proprietress as she reentered the room; she loudly intoned, “Tongues that wag may soon find themselves cut off from their supper.” The four traders muttered apologies, and went head down back to their plates.

So my Yankee pot roast was fine, but my curiosity about this delicacy, confined to a single neighborhood in Chicago, was not abated. Indeed, I think I was quickly becoming obsessed with it. Someday, when I find it a damp, drizzly November in my soul, I will have to go in search of this great lake cow. What a tale I’ll have to tell then—for there is nothing they love in Yankee Town so much as a good tall tale.

Call me editor of Fooditor.

Cover image: Carol Highsmith

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.