WE’RE SITTING IN TJ CALLAHAN’S FAVORITE BOOTH at Farmhouse in River North—favorite because of the table, which was reclaimed from a south side factory and has the well-worn bumps and gouges to show it. The bartender brings over two bottles of a cider called DTW, which Callahan explains was called “Tell William” until they realized there was already (of course) a cider called William Tell, at which time legal caution suggested a change to “Don’t Tell William.” These are two of the very last bottles of the 2014, which he doesn’t mind opening because the 2015 vintage—five different varieties, all made exclusively for Farmhouse—will be introduced at a tasting event on August 3, benefiting Familyfarmed.org, the group behind the Good Food Festival.

The bartender pours it and I give it a taste. Crisp, clear, a very slight hint of funk such as you sometimes get from wine (or cheese), you might identify the taste of apples right off, or you might struggle to pinpoint it, depending on your experience of hard cider. It’s refreshing and dry; I say I like it. Then Callahan, one of the owners and managing partners of the Farmheads Group which owns Farmhouse Chicago, Farmhouse Evanston and Farm Bar in Lakeview, makes his pitch for why I like it.

Michael Gebert

Michael Gebert TJ Callahan with DTW

“What you may or may not know about cider is, cider is just like wine. It’s a fruit that’s ready in the fall, that will naturally turn into an alcoholic beverage on its own. But the vast majority of ciders in America are made from culinary apples,” he says. “It’s just like you going into the supermarket, buying those grapes, crushing them, and wondering why you didn’t make a wine as good as Caymus. Because it’s the wrong grapes.”

The apples they use for their cider are, he says, true cider apples—mainly because they have the tannins that provide structure, to use a wine word. In the trade they’re called bittersharps and bittersweets. “Bittersharps and bittersweets are way too tannic for eating,” Callahan says, but that’s what gives the cider the crisp dryness that makes for a beverage both refreshing like beer and deep like wine. The 2014 DTW was a 70% blend of a modern variety called Liberty with 30% from two English cider apples, Brown’s Apple and Tremlett’s Bitter. “The amount of true cider apples grown in America, you could put on the head of a pin,” he says. “If it was just the Liberty, it would be nice, but it wouldn’t have the same complexity.”

So how do you make cider if not from apples that are meant for cider? “A lot of the American ciders that are made by the big companies, they’re making it from apple juice concentrate, fermented sugar water,” he says. A step up from that is to make it from culinary apples “using good winemaking techniques, and they can make something very drinkable. But it’s not going to have the same mouthfeel.” Some may blend in a little of the bittersharp or bittersweet production for the tannins, but the degree of access to those cider apples that Farmhouse has, Callahan says, is shared by only a few other producers who have also planted their own true cider apples.

Brown Dog Farm

How did this come about? Callahan comes out of the world of restaurant mergers and acquisitions; one of the deals he helped put together involved two little companies called Chipotle and McDonald’s. Farmhouse opened in 2011 with the intention of bringing local midwestern farm food into a casual bar setting—”farm to tavern”—and in 2012 Callahan and his wife bought an abandoned dairy farm near Mineral Point, Wisconsin, and named it Brown Dog Farm.

“Right off the bat I started thinking about, how can I farm this for Farmhouse?” he says. One of the things he did was plant apple trees, with the idea of making cider eventually. But it takes a few years for apple trees to bear much fruit, and he felt that cider was on the rise—by now it’s the fastest-growing beverage category—and wanted Farmhouse to have its own cider you couldn’t get anywhere else, sooner rather than later. He mentioned this to a neighbor who has an organic vegetable garden—and it turned out that just a mile up the road, the answer to his desire for a source for cider apples was already growing.

Burning the fields at Brown Dog Farm

“WE LOVED THE LAND, BUT WE WEREN’T SURE WHAT KIND of business we wanted to do on it,” says Deirdre Birmingham. She and her husband John bought their farm near Mineral Point in 2002. By 2003 they had the answer: “True cider apples, farmed organically. We wanted to create a product, a quality product that we could market, not just to sell tomatoes at the farmers market.”

“Nobody was talking about cider” at that point, Deirdre admits. The cider boom was years in the future, but so were sufficient harvests to make cider, so in the meantime, she took a grafting class and made contacts with others who were already growing cider apples in the Wisconsin region—important proof that they could be grown here at all. One was Dan Busse, who now manages the orchard for Seed Savers in Iowa; he was growing in Wisconsin then and she bought stions—those are the shoots that you graft onto your rootstock— for several cider varieties from him. With serious business, not just a pretty orchard, in mind, she planted her orchard like a vineyard, grafting onto dwarf trees which are held up by trellises, like wine grapes. (It’s a lot easier than picking from a ladder.)

“We grow horrible tasting apples,” Deirdre laughs. “Ugly looking, too. We don’t care what they look like—they’re just going to get smashed.”

Today they grow about 10 or 12 varieties, some English and French varieties (though those are prone to a disease called fire blight), others disease-resistant hybrids developed in the U.S. for cider production, such as the Liberty, which was developed at Cornell, or the Priscilla, whose name comes from the three universities that collaborated on it—Purdue, Rutgers, Illinois. “We grow horrible tasting apples,” Deirdre laughs. “Ugly looking, too. We don’t care what they look like—they’re just going to get smashed.”

Matt Sweeny

Matt Sweeny The only beverage they produced wasn’t cider but apple brandy, made from their apples by a local distiller and sold only on the farm itself. Meanwhile the Birminghams did some surveying of the cider market—”We came to the conclusion that you grow the market one cider drinker at a time,” she says. “People don’t know what it is, they don’t know what to expect—you have to educate them.” The plan was to find a good winemaker and then try to bring the resulting cider to market. But that hadn’t happened yet when her neighbor contacted them, saying there was a new farmer who owned restaurants and was looking for a source of cider apples.

TJ Callahan sums up their meeting: “I said wait a minute, I have restaurants, you’ve got juice, I could find a winemaker. I’ll put this all together, so I can sell the cider through Farmhouse—and how cool could this be?”

“I can see the barn on his farm from our house,” Deirdre says of Brown Dog Farm. “He saw what we were doing, and he has a genuine love for cider. So we got together to produce a well-crafted, well-made, sustainable product.”

TJ Callahan (center) with Deirdre and John Birmingham

Callahan already had a connection with Fox Valley Winery in Oswego, south of Aurora. That the winery was in Illinois was important, because it’s far less of a legal hassle to bring apple juice across state lines and make cider from it here, than to bring cider into Illinois. The juice is frozen in big containers at a cold storage warehouse as it’s crushed—different apples are ready for crushing at different times—and shipped to Fox Valley when it’s time to make cider. “Then we thaw all the juices out there, and have an all-day tasting session, comparing and contrasting and making our decision about what juices will be blended,” says Callahan. “We’ll go out several times in the winter and in the spring, and taste how they’re coming, and make our final decisions about what we want to sell.”

Strategically, Callahan sees it as a way to draw people to his three Farmhouse bars—”You try it and like it, it’s something you can’t get anywhere else,” he says. “We rolled these out about a year and a half ago, and roughly 20% of my draft sales now are cider.”

All numbers having to do with cider are on the rise—”Deirdre, if she wanted to, could sell her juice for $15 to $20 a barrel to other cider makers, that would use it to provide backbone to a cider that would be mostly Red Delicious or Galas or something,” Callahan says. So the Birminghams are on an aggressive expansion plan—right now they have about 6000 of their dwarf trees strung along trellises like wine grapes, but they added 2200 new graftings last winter, and plan to add 3000 more this winter. They plan to add 3000 to 6000 new trees a year for the foreseeable future.

“It’s really ramping up,” Deirdre says. “We’re the largest producer of cider apples in the midwest, and the only organic one in the midwest. We’ve climbed a steep learning curve, but it’s great to go through the struggle and find people like TJ and the consumers at Farmhouse who can appreciate that.”

WITH TWO NEW CIDERS DEBUTING this year, that makes five different offerings for Farmhouse. The new version of Don’t Tell William has been adjusted with four different traditional cider apples besides the primary apple, Liberty. Also returning will be Free Priscilla, which is based on the Priscilla apple plus the traditional English Tremlett’s Bitter, and is described as having caramel notes. And they’ll bring back an oak-aged cider called Touchwood, which includes Red Delicious and Haralson apples and has vanilla aromas from the oak. There will also be two entirely new varieties: Halflinger, named for an Amish workhorse (there are Amish in the Mineral Point area), uses Red Delicious, Honey Gold and Regent apples, and is the driest of their ciders, while Fort Jackson, named for the pre-Civil War fortification located where Mineral Point is now, takes Red Delicious and Haralson apples and adds Equinox hops for a floral hopped flavor.

All of these can be tasted at their launch event at Farmhouse Chicago on Wednesday, August 3, from 6 to 8 pm, as well as appetizers using honey from Brown Dog Farm by Farmhouse head chef Eric Mansavage and crew; tickets are $25 here and all proceeds go to Familyfarmed.org.

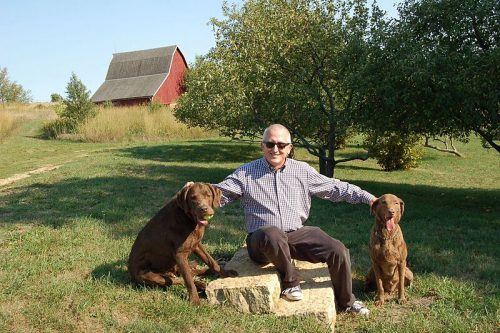

Brown dogs at Brown Dog Farm

“I couldn’t be more excited, I’m like a Golden Retriever puppy,” Callahan says. “Other people think I’m crazy to do this stuff, but cider’s really important to us. It’s such a midwestern thing. It’s such a farm thing. Way back when, farmers were judged by the quality of their cider. The apples come in, you’re only going to eat so many apple pies. Cider was the way to preserve the bounty of the fall through the year,” he says—as we sip on the last taste of 2014, and discuss the 2015 harvest coming soon in bottled form.

Michael Gebert is the editor of Fooditor, the apple of his eye.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.