SUMMIT IS A LITTLE-KNOWN SUBURB on the southwest edge of Chicago, the place where all the South Side city buses turn around. “We get all the weirdos off the buses,” says Dan Zygmunt, who tends bar at Chester’s, makes pizzas, and has worked there since he was 16. It’s a blue collar suburb, hit by the decline of manufacturing jobs, increasingly Mexican in population (and certainly in its restaurant population). But on Archer Avenue the history—even more, the flavor—of 20th century Chicago remains alive in one business. Or two, or three, depending on how you calculate it.

It’s Chester’s tavern, one of those places that was the real City Hall, the real center of town, going back to about 1908. It was a place the Outfit tried to muscle into in the 80s and 90s, among other stories (isn’t that Evel Knievel on the wall?). But the story of Chester’s is also the story of the vintage Italian-American food at Orsi’s, and the pizza—which by the way, is one of the best classic tavern cut pizzas in the city. I don’t mean that casually, like one of the 50 best—I mean like, it might be the best. Or second or third or fourth, at lowest. It’s an old school pizza that tastes like the history of the Chicago area.

Go for the pizza and beer. Stay for the stories.

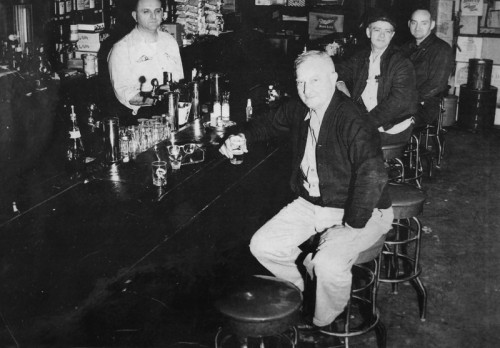

Chester, one of them, at the bar in the early 1930s

SUMMIT, OR SUMMIT ARGO AS IT’S ALSO KNOWN, is obscure, but it also has literary immortality—thanks to Ernest Hemingway in his story “The Killers,” which pretty much invented the sardonic dialogue of gangster movies from Cagney to Tarantino. Two hired killers looking for a guy named Swede go into a diner with a sign for its dinner special, and get to talking about the two-bit town they’re in:

“What do they call it?”

“Summit.”

“Ever hear of it?” Al asked his friend.

“No,” said the friend.

“What do they do here nights?” Al asked.

“They eat the dinner,” his friend said. “They all come here and eat the big dinner.”

Of course, the fact that Swede thought he could hide out in Summit tells you it wasn’t a big deal, a sleepy backwater compared to well-connected, rat-a-tat-tat suburbs like Cicero. Maybe so, but the fact is that the Capone mob in those days had its operations, bookies and taxi-dance halls (where the dancing could wind up horizontal) and clip joints of all sorts, in all the little towns along Chicago’s southwest border. The wild southwest.

Still, for most people who lived there Summit was just another working man’s town. The biggest thing in town was the Argo corn starch plant, which had a Pullman-like company town. Locals identified themselves by whether they lived in Argo, Summit, or all of six or eight blocks up north in the paradoxically named Deep Summit.

And the center of town was always Chester’s, which for some reason was a Cubs bar near the south side. I asked Dan why, and he just said, “I don’t know. It always was.” In 1959, an Argo boy, Ted “Big Klu” Kluszewski, who’d been traded by the Reds to the Sox, led an 11-0 rout of the Dodgers in the first game of the World Series. A photographer from the Sun-Times took a picture of Chester himself and Kluszewski holding up the headline, for the sheer novelty of Chester’s being Sox fans for a day.

Chester behind the bar, 1950s.

The Strzelczyk family owned Chester’s. The son’s name was Chester, everybody agreed on that. But nobody that day could remember if the old man was named Chester, too. The old man opened the bar in 1907 or 1908, making it the oldest commercial building left in town. There were 52 bars in the small town back then, I’m told, but Chester’s was the most important—as demonstrated by the fact that three Strzelczyks would serve as mayor over the years, including the middle Chester’s sons… another Chester, and Joseph. (Joseph Strzelczyk died in office last May. He was replaced by Sergio Rodriguez.)

Everybody went to Chester’s. Election parties were held at Chester’s, high school football victories were celebrated at Chester’s. Chester’s was where Argo workers cashed (and spent) their checks. The end of the bar used to be a cashier’s cage, and Chester once gunned down a robber who had become a little too predictable in showing up on payday.

That was when Summit was a bustling town where immigrants found the blue collar American dream and a few knuckles got scraped in the process. A Pottersville that had no interest in turning back into some pantywaist Bedford Falls. But by the 1980s much of that manufacturing had faded and Summit was in tough shape—”It had a bad rap, you couldn’t walk down an alley,” Dan says. “It’s pretty nice now. The new police chief has really cleaned things up.”

There was one golden goose on the horizon in the 80s, though—riverboat casinos. All the little towns around one would get to wet their beaks with casino revenues. That brought the Chicago Outfit back into the area. Dan remembers seeing made guys like Tony Spilotro, who Joe Pesci would play in Casino, hanging around: “They had rabies to us,” he says, by way of explaining that ordinary residents knew to steer well clear of them. When Dan started working there at 16, he immediately got the nickname “Spider,” in memory of another classic Pesci scene.

Eventually the Feds broke up that end of the Outfit. Now Summit is like any midwest small town, a little rough around the edges but hanging in there. High school football is a big deal. On Alumni Night, the whole town spills out onto the streets for the party. “All the bars and restaurants advertise on Facebook, come to our place for Alumni Night,” says Dan. “Then everybody comes to Chester’s anyway.”

Esco Statues. Collection of Joe Testa

THE ORSI FAMILY HAD A RESTAURANT up the street since about 1955, Peter Orsi says, and his father Dick opened a pizza parlor next door to Chester’s in about 1971. In the early 80s Chester’s closed, and after a couple of years Peter, who was 23—”I didn’t know anything about beer, well, I knew how to drink it”—bought it and moved the pizza business into the reopened bar. It was mostly unchanged—original tin roof ceiling, original wooden bar, longstanding practice of keeping a dog on the premises. Though a few years ago they expanded into the space next door, which Dan says had previously been “a daycare for schizophrenic adults, they’d just sit out front and smoke smoke smoke all day.” Now it gives the place enough room for families to come and eat pizza.

There was one other addition to the decor—a long row of classic movie star statuettes, made by a company called Esco, which were dorm room fixtures back in the day. The first time I mention them, Dan says “Those got a history to them, but I don’t know if I can tell you about it.” He goes to the end of the bar to ask Peter, and I can see Peter wave it off with a grin. “He bought them off a guy just before he blew up,” Dan says. “Joe Testa, who started the big trailer park in Justice—he paid him $100 for them right before he got blown up. You used to be able to get a thousand bucks for them—now you can find whatever you want on Ebay.”

One time, while his wife went off to church, Evel rode his bike right in the front door and smashed into the jukebox.

And this is where Evel Knievel enters the story. Back in the 1970s, he and Dick Orsi became friends because Orsi helped supply some authentically tough guys to work security at the biker’s stunt show. Evel would hang out at the bar, his presence loudly announced by the bus painted with his image parked across the street, a local hero to the kids to whom he would preach bike safety. One time, while his wife went off to church, Evel rode his bike right in the front door and smashed into the jukebox.

Back to pizza. The Orsis brought over all the recipes from both of the family’s restaurants, as well as the hulking pizza oven, black as the bottom of a coal mine, so old the nameplate of its manufacturer had long since fallen off, leaving only two drilled holes. The pizza tastes like old time Italian—a cracker thin crust, sausage with fennel and a tomato sauce with a Sunday gravy depth and a lot of red pepper kick. Dan tells me the recipe is the same as the restaurant used in the 1950s. As if I could have doubted it for a second.

Sometimes New Yorkers get hung up on Chicago crusts being undersalted, which matters when you have a puffy, tossed French bread crust. But the hyperflat Chicago tavern cut crust is a pure textural element, and I defy anyone to eat this and think it’s lacking anything in the flavor department; it’s pretty much perfect as a blend of crunchy crust, tart tomato, and gooey cheese and sausage.

Besides pizza, they have a full menu of Italian-American dishes, as well as lunch specials—I had just missed the Italian pork sandwiches that day. I haven’t tried anything else, but I bet it’s as satisfying as Italian-American gets. What do they do for fun in Summit? They go to Chester’s, which is also Orsi’s, and they eat the big dinner. Like they always have.

Michael Gebert is editor and mayor of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.

I grew up in Summit. Fantastic article! It’s been many years since I had their pizza. Must get it soon!

My Grandpa was one of the three Strzelczyk’s, great piece of history for me. Thanks for this!