SOME PEOPLE MAKE RESOLUTIONS AT NEW YEAR’S, but mine come in spring, when the first spring fruits and vegetables start to hit the farmers markets—strawberries and asparagus and ramps. This will be the year, I resolve, that I go to the markets and buy these fresh and wonderful things and eat my fill of beautiful vegetable dishes, all season long.

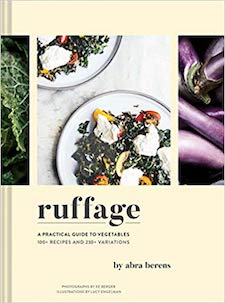

It doesn’t come naturally to me because I grew up with meat the center of the plate, and vegetable was another word for side dish. Side as in shunted aside, cooked in one simple way while the focus of chefly efforts remained on the meat. I don’t know how to cook spontaneously in that way—to consistently turn out the kind of healthy-feeling magic that comes from a fresh vegetable and a few simple hints of sweet or sour. Which is why this year I will have at hand Abra Berens’ Ruffage: A Practical Guide To Vegetables (Chronicle Books, $35), the ultimate cookbook for cooking from farmers’ markets, from one of the first people I’d ask for advice on that subject.

The book

If you’ve met Abra Berens, it was probably during her tenure as the chef of Stock Cafe at Local Foods. That was one of the few times she was front and center in a Chicago restaurant. I’ve tended to run into her behind the scenes—like the time I was riding the elevator to Everest to talk to Jean Joho about Julia Child, and there she was with a bushel of freshly picked something, black soil still clinging to the roots. She’s worked for places from Zingerman’s to Vie, and is currently chef at Granor Farms in Three Oaks, Michigan. But at least as much as she’s been a chef, she’s been a supplier of grown things from Bare Knuckle Farm, near Traverse City in Michigan, which she owns and runs with a friend, Jess Piskor. Cooking in Chicago has often been just what she did during the winter, while growing for other chefs—and to feed herself and her husband Erik—has been her real work.

Often chefs who talk about healthy, natural ways of eating do so from a position of wealth and privilege. Berens is different because she’s a real farmer, often scraping by, and a real cook, too, which isn’t that much different. But the first skill people in either category learn is to make as much as possible out of however little you have—this is a book about making glorious meals out of what’s fresh and at its cheapest in season. It’s a vegetable cookbook, not a vegetarian one, largely free of moralizing—instead, it’s a book about how lucky we are that this amazing stuff just comes out of the ground, for us to eat! As she writes about her first winter as a farmer, “I couldn’t have bought food in the store of this quality if I had had dollars instead of pennies. I was broke as hell but I was eating some of the best meals of my life.”

I interviewed her about her book, which was just named one of the 12 best cookbooks of spring by the New York Times, by email. She’ll have several events beginning this month in the Chicago area; a list will be at the end of the interview.

Photos by EE Berger

Abra Berens

FOODITOR: The book is organized by vegetables, but it’s also about having a well-stocked pantry and some techniques like roasting or braising down, so you can improvise with whatever happens to be growing at the moment. Tell me about how you see your approach.

ABRA BERENS: Those two ideas are intimately linked—having a strong pantry and having a handful of techniques that one feels confident using to prepare whatever comes your way. It is sort of like solving an equation. If you have A + B + C = D that doesn’t get you anywhere. But if A is the ingredient, B is a pre-prescribed technique for preparation, and C is the condiment or sauce from your pantry it is a lot easier to make D dinner quickly and easily. With a million different variables, in the form of recipes that don’t overlap it is harder to solve.

The other metaphor I tend to use is of a quiver full of arrows that you can draw from at any given moment. But I’ve found that without explicit instruction (i.e. a recipe for a specific vegetable) it is harder to make the link in reader’s minds. I hope that Ruffage builds those foundational skills so that eventually readers will cook beyond the page depending on what they have on hand.

So many of us are so used to meat being the center of the plate—how do you make a vegetable meal as fulfilling?

I think of it as a choir versus a solo singer. Instead of relying on the one voice to make a meal, bring together a lot of harmonies. Three dishes with different levels of spice, different textures, different colors.

And that doesn’t mean three complex dishes. My ideal vegetable focused meal would be a big salad (maybe with hard cooked egg and bacon and a very lemon heavy dressing), a pile of roasted vegetables (like carrots with nothing more than a handful of chopped herbs over the top), and something cooked and soft like a sweet potato puree with a spoon of chili oil or pounded walnut relish over the top. All of that could even go on the same plate.

Your parents were both in medicine—an anesthesiologist and a registered nurse—and yet they also had a farm and grew their own food. Tell me about how growing up around food like that affected you.

To be clear both my parents were anesthesiologists, my mom had a ND (nursing doctorate) but they did the same job and maintained privileges at each of their respective hospitals. Which also means that they worked a lot. Food was our time to connect. My dad is a notoriously slow eater. Our meals would often last 2-3 hours even during the week. He would always say, “You are welcome to leave, but I’m going to stay and finish this.” We rarely left and finding that time to be slow with each other feels foundational to me now. I’m sure at the time it annoyed me a bit.

Ramps

In a weird way, farming pickles (my dad’s family’s career) didn’t feel that connected to food. We just grew them and sold them—inputs and outputs. Our garden was a little different—we worked on it together, bringing food from the garden straight to the table in the summer. But it was the act of eating, sitting together, often with candles lit, to take the time to talk and be with each other. One of the daily luxuries that we really celebrated.

I think it very easy to overdo it with spices. I almost always want more herbs, which add great pops of flavor but can be used a bit more recklessly.

Most of us think of herbs and spices as being basically the same thing, but as a grower you make an interesting distinction between herbs which you grow, and spices which come from around the world.

I hadn’t thought about it quite like that—local vs non-local—but it is a good distinction. I don’t take issue with eating non-local food, and so there isn’t a moral equivalency there for me. That said, I think that until we solve the energy crisis, it feels very silly to ship perishable crops that are full of water (lettuce, cucumbers, herbs). In my ideal world we would have a system where local ag could supply high quality perishable crops and then transport non-perishable dried crops.

Back to the particulars of herbs vs. spices—for me I think it very easy to overdo it with spices because they are so intense. I almost always want more herbs, which add great pops of flavor but can be used a bit more recklessly.

The book includes what I think can only be called a love letter to cabbage (“Tomatoes are darlings, it’s true, but they are around for only a handful of weeks… not you, cabbage. You are ready straight from the field or after months of storage”) Why cabbage?

I truly love it. In a lot of ways, I’m a pretty simple person with simple tastes. Cabbage is my most used ingredient, one of the few things I have on hand 90% of the time. There is added benefit that I could use that chapter as a way to sing the praises of the most common of ingredients—to put a little shine on the practical and every day. Plus, I figured the most common question I would get is “what’s your favorite vegetable?” so it seemed efficient to have an answer already articulated.

Celery root

You propose the idea of “whole plant cooking” at one point. What does that mean?

Just that, using the whole plant. Most ingredients have more to them than the prized bits. Beets have long stalks and broad leaves next to those roots. A head of cauliflower is about 40% of the total plant that can be eaten. I didn’t know what I was missing until I sautéed turnip greens with white wine and chili oil or used the long, unruly stalks of fennel to support fish during a quick poach.

We’ve talked for years about nose to tail or whole animal eating, and I hope that that idea trickles down to vegetables (all ingredients really). I think this is important because it means that we will utilize more of the plants that we grow and thereby the resources it takes to grow them will be more efficient. Plus, a lot of people are working with very tight household budgets (myself included); by getting three dishes from one fennel bulb, my grocery dollars go further and that is an equalizing factor.

You worked for Paul Virant at Vie, who has such a focus on preservation, and obviously anybody who grows stuff is going to wind up preserving a lot of it. What do you preserve?

Paul taught me so much about preserving, and I still can lots of pickles and jams. But now that I have a chest freezer, I do a lot more freezing. Right now, the recipes from Ruffage that are in my deep freeze are peperonata, caramelized onions, beet puree, squash puree, roasted eggplant puree, braised eggplant, frozen peas, frozen corn and on and on.

Beyond the specifics of preserving Paul taught me what to do with those ingredients. Not specific recipes but how to build a dish based on what is in your pantry. Several times we would be in the Vie pantry, looking at the jars, and he would be brainstorming a dish. He had the protein and was looking for ways to compliment it. That was a paradigm shift for me, and my food/thought process was forever altered.

What are you most excited about growing, and cooking with, this year?

We just started growing sweet potatoes at Granor Farm last year. They were the best sweet potatoes I’ve ever had. I’m excited for those again. Katie, our farmer, is also giving a bunch of new chicories a go for me. I’m hoping they will be ready the same time as the sweet potatoes because I think the bitterness of the greens will play well against the potatoes.

How did the idea for the book and selling it come about? (You have some impressive contacts I wouldn’t have known you had—like Francis Lam, who does the introduction.)

I started writing a food column in Traverse City five years ago. Having an outlet for my writing and the discipline of writing two columns a month, was the start of the book. Several of the chapters are elaborations on the original column. From there, I have been fortunate enough to have the support of a broad community. A friend who introduced me to my agent who introduced me to the photographer of the book, and on and on.

Braised fennel

Abra Berens’ Ruffage release events in Chicago:

4/22: Pre-publication Farm dinner with Lula

4/23: Ruffage Release party at Field and Florist

4/28: Talk with Mollie Hayward at Read It & Eat

5/7: Dinner at City Mouse with Pat Sheerin

5/25: Demo at Chicago Botanic Garden

6/9: Dinner with Floriole

9/18: Dinner at Vie

Michael Gebert is the big cabbage of Fooditor.

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.