THE IDEA OF SPECIFICALLY JEWISH PRESERVES seems surprising at first, then completely natural. Much of Jewish culinary culture comes out of parts of the world, like Eastern Europe and Russia, where preserving food is a survival necessity. From jams to pickles to sauerkraut, these are the things grandmothers, including Jewish grandmothers, do. So why shouldn’t there be Jewish preserves?

For Chicagoan Emily Paster, it started with her daughter more than her ancestors. Having moved to River Forest (which meant she had to give up a job as an attorney for the City of Chicago), she was looking for kitchen activities she could share with her daughter, Zoe, who was about four at the time and had serious food allergies. Because she was preparing more of the family’s meals from scratch as a result of the allergies, she’d discovered the “many amazing farmers markets” in the area around River Forest, and she hit upon making jams because the recipes were simple and pure—just fruit and sugar.

The book

Fast forward a decade and Paster, now 43, has published The Joys of Jewish Preserving, which came out July 15. She gives talks, demos and classes all over the country and city, including a tasting and talk with book signing on Saturday at the Culinary Historians of Chicago, a harvest canning demonstration class at the Morton Arboretum on Aug. 26, and a launch party September 17 at Read It and Eat, a cookbook store at 2142 N. Halsted.

“I was always the person who bought too much at markets,” Paster admits, “and the first year we made a bunch of basic fruit jams: apricot, peach, easy stuff.” They also made simple pickles like old-fashioned dilly beans (green beans), because her daughter has always loved pickles. “It was fun, satisfying to do, and the results were delicious,” she says. “They also made great holiday gifts, and the reaction was gratifying. Our friends couldn’t get enough of them.”

Paster confesses she really got bitten by the bug and began teaching herself new techniques, helped by the general revival of preserving, which she sees as a possible offshoot of the economic downturn. “ I could buy equipment online, connect with other people who were doing the same thing, and improve my skills,” she recalls.

Not surprisingly, she ended up with far more pickles and preserves than she could possibly use, which is how the Chicago Food Swap came about. “I’d read about a food swap in Philadelphia, and the idea sounded perfect,” Paster says. “Home cooks, bakers, canners, and gardeners get together to trade and barter what they’ve made, grown or foraged. No money changes hands; labor is the currency.”

She set up the Chicago Food Swap in 2011, and although it was at a different location every month for the first few years, in 2014 it found a permanent home as part of the Peterson Garden Project’s Community Cooking School at the Broadway Armory Park Fieldhouse. Notices about meetings, typically every other month (though slower this year), go out to the 1,000 people on the mailing list and Facebook fans, among others. Paster says 35-50 people usually participate in the swaps, which take place year-round. Along the way she started a blog, West of the Loop, and writing about the Food Swap led to a cookbook of that name aiming to spread the idea in 2013.

Leigh Olsen

Leigh Olsen Cranberry applesauce with latkes

THEN, AS AGENTS TEND TO DO, HERS asked Paster what other book ideas she had. That inspired her to combine her two specialties—preserving and Jewish cooking—an idea that had been on her mind for awhile. “I love to entertain and had been preparing meals for the Jewish holidays since—well, since hosting a seder in my little law school apartment. And when we moved to River Forest, we joined a congregation, my daughter went to Jewish pre-school, and I basically ran a Jewish household, though not a kosher one.” She explains that Ashkenazi food—matzoh ball soup, gefilte fish, kreplach, etc—is nostalgic for her, because that’s what her grandmother and aunt made, but she also learned about Sephardic traditions when she spent her college junior year in Paris living with a Sephardic couple.

Thinking about her two culinary preoccupations made Paster realize how much of an overlap there is. “You can’t have a Reuben sandwich without sauerkraut, and latkes aren’t the same without apple sauce (even if some people prefer sour cream),” she points out. “The minute I turned in the manuscript for Food Swap I started working on The Joys of Jewish Preserving because I was so jazzed about it.”

The book took about a year to write and includes 75 or so recipes. It is divided into three chapters: jams, syrups, butters, and other fruit preserves; pickles and other preserved vegetables; and recipes to show off your jams and pickles, among them sweet-potato latkes, cheese blintzes, challah and semolina cake. All the recipes rely on ingredients used by Ashkenazi and/or Sephardic Jews, and each one has an introduction tying it to Biblical times, the diaspora, her own family favorites or other fascinating tidbits.

But before all that, Paster tackles an important question: What is Jewish preserving? She basically argues that the kosher dietary laws make it distinctive from other preserving in two ways. Because of the prohibition on mixing meat and milk (or any dairy, even butter), meals typically end with fruit, or fruit and nuts, as opposed to pastries. And since fruits are only available in summer in colder climates, they had to be preserved in season to be available year-round. In addition, she believes that the tradition of making preserves persisted longer among Jews because they couldn’t buy anything that wasn’t certified kosher, even as other people moved to cities and started purchasing products commercially.

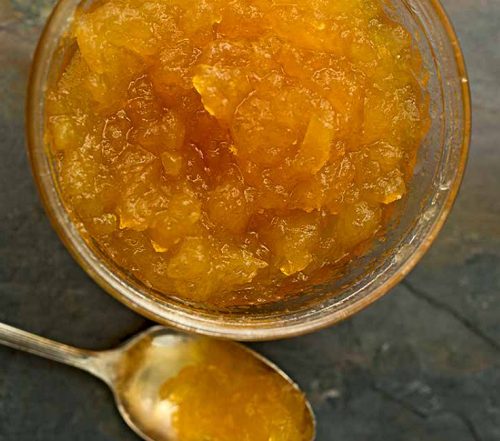

Leigh Olsen

Leigh Olsen Apple honey jam

To research the book, Paster turned first to her collection of Jewish cookbooks by authors like Joan Nathan, Claudia Roden, and Gil Marks, whose “Encyclopedia of Jewish Food” was a great resource. “I’d look up ingredients to see if they’re mentioned in the Bible, or the Torah, or when they were first noted,” she says. “There’s a lot of information; because of the kosher laws, food was almost an obsession.” She also consulted a variety of other sources. For example, she learned from a gardening web site or book that gooseberries, beloved in Europe, are little known in the U.S. because the government banned their cultivation (and that of currants) in the early 1900s, believing them to host a disease that infected pine trees—a ban that wasn’t lifted until the 1960s.

While Paster is careful to put the recipes in historical context, she’s equally concerned about adapting them for the way people cook now. One of her favorite examples is Lemon Walnut Eingemacht, a syrupy preserve traditionally made with etrog (citron), which is used ceremonially at the grain-harvest-festival Succot, and first served atTu B’Shevat, the minor holiday at the beginning of the Biblical agricultural cycle. Because the bitter thick-skinned citrus fruit requires extensive preparation and in America is usually grown using lots of pesticides, she recommends substituting lemons.

For Peach Lekvar, one of the fruit butters that traditionally was boiled down for hours in a kettle over an open fire, with people taking turns stirring, she suggests a slow cooker. She also points out that lekvar, which is the consistency of butter but has no butter in it, provided a way for the Askenazi to use less sugar, which was more of a luxury for them than for Sephardic Jews, who had ready access to it and tended to candy fruits more.

Some of the recipes Paster simply made up, melding traditional flavors and legends. Queen Esther’s Apricot-Poppy Seed Jam, for instance, brings together two Purim mainstays—apricots and poppy seeds—that normally aren’t combined in jam. Several stories explain the presence of poppy seeds at Purim, among them the notion that Queen Esther subsisted on them during a three-day fast while she prayed to God to reverse Haman’s murderous decree. For Charoset Conserve, Paster was inspired by typical Askenazi apple-based version of the Passover condiment representing the mortar used by Jewish slaves to build the pyramids (Sephardic versions have different ingredients) and her mother-in-law’s recipe, but it’s her own creation.

Leigh Olsen

Leigh Olsen Sweet and sour peach ketchup

The book has more recipes for jams and other sweet stuff than for pickles, which Paster says is often the case with preserving cookbooks and what people seem to want. Her target was 75 recipes from the outset, though some of them changed along the way as she and one other tester—every recipe was tested at least twice—tried them out. “I knew I wanted a black radish pickle, because black radishes are mentioned in the Talmud and were one of the earliest crops cultivated by both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews,” she explains, “but the fermented black radish was so smelly, we settled on a quick-pickled version. We didn’t want to turn people off.”

As to her favorite recipe? “The Plum Lekvar is fabulous,” she says. “It’s delicious on bread, or spooned into yogurt, or as a filling for hamantaschen (the classic Purim dessert). I’ll probably be making it for the rest of my life.”

Anne Spiselman is a freelance writer who has covered food, wine, and culture for decades. She’s a frequent contributor to Crain’s Chicago Business and Edible Chicago and has written for most local publications and some national ones.

COVER IMAGE: Doug McGoldrick

Latest

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you're not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register with Disqus.